Editor’s Note: As a new PBS documentary revisits the life and work of Ernest Hemingway, our latest Magazine Classic looks back to 1985, another period of literary reconsideration and biographical exploration that shed new light on the legendary author’s characters and character.

The elevator opens on the fourth floor and I know I’ve arrived. A leopard skin stretches across a white wall, its tawny spots glossy under fluorescent lights. A few steps away an impala head, horns delicately curved, stands mounted above a fake fireplace. It is unmistakable: I’m in Hemingway country.

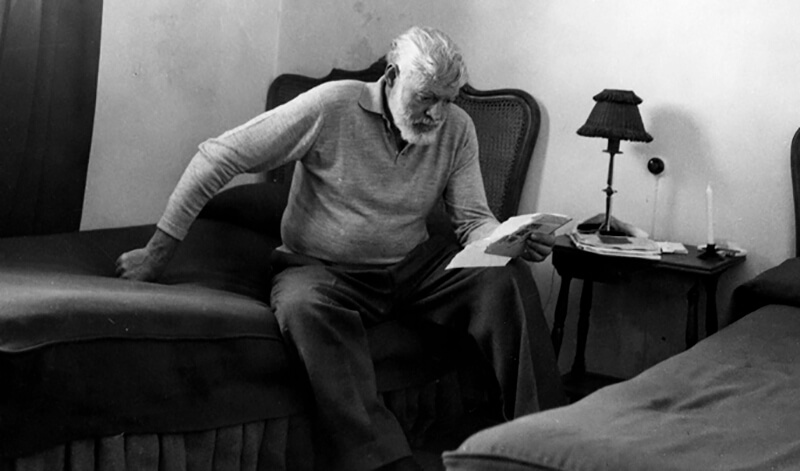

One wall is lined with books, the foreign and domestic editions of his works. Another is crowded with photos tracing his life from its Midwestern beginnings in Oak Park, Illinois, and Petoskey, Michigan, to Paris, Pamplona, Venice, Nairobi, Havana, Key West, and the last days in Ketchum, Idaho. It is a snug, well-lighted place.

And an improbable one. The Hemingway Room is located in none of the locales of his life but in Boston — in the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, I.M. Pei’s white stone and dark-glass shrine on Columbia Point overlooking Boston Harbor. The writer himself was in Boston only once — as a sixth-grader touring the historical sites with his mother — and the spare style, exotic landscapes and rough action of his fiction are far removed from the city’s stately literary traditions. Scribner’s Magazine was banned in Boston when it serialized A Farewell to Arms. Yet along with its materials and mementoes of the 35th President, the striking Kennedy Library houses the bulk of Ernest Hemingway’s papers — and scholars are flocking to the fourth floor to use them, creating new interest in the novelist’s life and work. Hemingway is again a hot property in the world of literary scholarship, and the Hemingway Room is the center of new activity.

On the day I arrive, however, I am alone in the room. Joan O’Connor, the collection’s curator, brings a file of Hemingway’s letters to one of two worktables. The window at my elbow looks out to the harbor islands, the sky and water an unbroken gray on this rainy day. I begin to read; the letters are typed and long. They were written from Havana in the early 1950s to Charles Fenton, a Yale professor who was putting together one of the earliest studies of Hemingway’s art. Hemingway was both helping Fenton and trying to discourage him, an inconsistency that caused him to write the professor as many as three letters a day.

I am hunting for something specific, but the letters are fascinating in themselves; soon I’m reading more than I need. They are hurried, unbuttoned, marked by an overpowering personality that could bring words to life and make life seem more real. Lillian Ross once pointed out that in these letters Hemingway casually created a second body of work that was free and loose and full of a private shorthand that contrasts with the exacting control of his formal prose. “I write them instead of stories,” he explained in a letter, “and they are a luxury that gives me pleasure and I hope they give you some too.”

In his life, Hemingway unabashedly created a striking public persona, but he had a private side, too; and he did not want his letters published after his death. “I write letters because it is fun to get letters back,” he explained, “but not for posterity. What the hell is posterity anyway? It sounds as though you meant you were on your ass.” He left instructions forbidding their posthumous release — but his widow, Mary Hemingway, printed some in her 1976 autobiography, and then allowed 600 to be published in a 1981 collection.

Hemingway also was not eager to have people like me poking about in his private papers. Studying his work was one thing, studying his life quite another. “The writing published in my books is what I stand on,” he wrote Fenton, “and I would like people to leave my private life the hell alone.” He told Arthur Mizener, a biographer of Scott Fitzgerald, that he wanted “all my papers and uncompleted MSS. burned when I am buried.” That would not happen, of course, and Hemingway must have known it. For despite vacillations in his critical reputation both before and after his death, he was unquestionably a major American writer, and major writers attract a scholarly crowd insistent on access to the literary remains. It is the price of the life beyond life which every writer knows is real success.

Hemingway’s literary reputation plummeted soon after his suicide in 1961. Some of the reasons were societal: Reaction to the Vietnam War and newfound concern with women's rights and social reforms made his manly, outdoor world seem narrow and archaic. The same was true of his fascination with bravery and with the chivalrous conduct of the stoic individual; in a complex society such matters had been left behind. Writers like Saul Bellow, John Updike and Philip Roth came to the fore in the 1960s; their accounts of characters struggling with psychological ills, domestic relationships and the tides of mass culture seemed more in keeping with the times. Their characters were men in society, whereas Hemingway’s heroes contended with the romantically remote and elemental — bullfighting in Spain, a charging rhinoceros in Africa, a young man in love in wartime Italy, an old man and the sea.

In university classrooms the rage in those days was for writers of moral fables like Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., or experimental writers like John Barth and Jorge Luis Borges who made the forms and methods of fiction their subject and offered characters more symbolic than substantial. Professors spoke of metafiction and fabulation, and turned the heavy guns of semiotics and deconstruction of fictional texts. By contrast, the Hemingway style appeared excessively plain and limited in range, and his romantic realism lacked the complications demanded by modern literary analysis.

Also, a notion arose that in allowing himself to become a public figure — the Papa Hemingway of the magazines, the swaggering sportsman and friend of the rich and famous — Hemingway had wasted his talent, becoming a blustery shell of the young writer who in his early stories and novels had created a fresh and widely emulated prose style. Carlos Baker’s 1969 biography, Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story, did little to lift the reputation. It was thorough and admiring, but it shed light on all the unattractive niches in the novelist’s character: He had been boastful, compulsively competitive, and unforgiving of those — like Sherwood Anderson, Gertrude Stein and Scott Fitzgerald — who had the misfortune of once offering him advice or lending a helping hand with his career.

Then the tide turned. By the early 1980s, Hemingway’s work was enjoying renewed popular interest and scholarly appreciation. In part, it was a natural swing of the literary pendulum. But it also seemed tied to shifting attitudes in the country — a diminished concern with social and ideological issues, and an increased emphasis on personal experience, including achievements of craft and style. Also, it may have had something to do with a growing weariness with the narrow concerns of a lot of modern fiction, a thin and introspective world compared to Hemingway’s robust and adventurous one.

Beyond such matters is the simple fact that Hemingway has always been among the most accessible of major writers. He does not pose the difficulties of Herman Melville or Henry James or his great rival William Faulkner; readers of all sorts have read him with pleasure and ease. And in his life he never exuded the off-putting aura of the highbrow literary figure. He took literature seriously but never solemnly: it was “just writing as well as you can and finishing what you start.”

Hemingway scholars are drawn by the same qualities that attract general readers. They start with pleasure, then proceed to other, presumably more weighty matters. “If you are going to work on something, who says you can’t like it?” asked Philip Young, one of the first and still among the most interesting Hemingway scholars.

My own experience in the Hemingway Room bears Young out. After I finish my work I linger, enjoying the quiet and the view, reading for sheer pleasure. I request more letters (to Archibald MacLeish, Lillian Ross, John Dos Passos) and then clippings of the newspaper work which Hemingway did for The Toronto Star in the 1920s, written under his own name and under the pseudonym John Hadley. Young Hemingway was one of the paper’s prize writers, and it gave his lengthy feature stories splashy treatment. A house ad in a 1923 edition promoted him, at age 24, as having “not only a genius for newspaper work but for the short story as well. He is an extraordinarily gifted and picturesque writer.”

A collection of the Toronto journalism will be published this year by Charles Scribner’s Sons, Hemingway’s longtime publisher — and he wouldn’t have minced words about that development either. He told Charles Fenton (in a sentence that is a fair sample of his letters’ headlong style) that he considered “few things worse than for another writer to collect a fellow writer’s journalism which his fellow writer has elected not to preserve because it is worthless and publish it.” But that is what happens when a person becomes one of the canonical American authors: Everything (good, bad and indifferent) appears between covers.

The major Hemingway books are all still in print. Some 750,000 copies are sold annually in the United States, up a quarter in recent years. He also is among the most widely translated American writers; his estate earns around $80,000 a year in foreign royalties. He is doing equally well these days at the hands of scholars. For more than a decade now he has kept company with Melville, Hawthorne, James, and Faulkner as the five American writers drawing the most scholarly attention to print.

Hemingway’s critical comeback is actually his second; the first came during his own lifetime. After the big success of his early fiction — especially In Our Time, The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms — he fell out of favor with the critics. In 1950, with Across the River and into the Trees — a work that seemed a windy parody to his style and subject matter — his reputation hit bottom. He began to seem a writer like Thomas Wolfe who (in Max Geismar’s phrase) gets smaller as you get older. Then came a short masterpiece, The Old Man and the Sea, and in 1953 the Nobel Prize for Literature. Hemingway was back as the writing trade’s reigning heavyweight, and he remained in contention for the rest of his life.

That he is back again owes in good part to the opening of his papers for general use in 1975 and of the Hemingway Room in 1980. Scholars, those musty types he called “Buzzards of the World Inc.,” have been poring over his work ever since.

When a young woman takes the worktable behind me to read a file of President Kennedy’s speeches, it occurs to me that the bull market in Hemingway studies may also have been helped along by rubbing shoulders with Camelot glamour. In life, Ernest Hemingway and John Kennedy never met; though Hemingway was among the writers and artists invited to the inauguration in 1961, he was hospitalized at the Mayo Clinic and could not attend. After watching the ceremonies on television he sent J.F.K. a message: “It is a good thing to have a brave man as our President in times as tough as these for our country and the world.” Hemingway’s papers found their way to Boston sometime after President Kennedy helped Hemingway’s widow travel in Cuba following the Castro revolution (she struck a deal with Fidel, giving him the Hemingway home and its library of 9,000 books in exchange for the papers, manuscripts, and art collection inside). Much later, grateful for Kennedy’s help, Mary Hemingway gave her husband’s papers to the prospective Presidential library.

It was a generous act and, in the effort to rehabilitate Hemingway’s reputation, even a shrewd one — since scholars in large numbers are more likely to be drawn to Boston than to Petoskey or Ketchum. The collection includes several stages of Hemingway’s published books (manuscripts, typescripts, galley proofs); some 600 drafts of stories, articles and poems; miscellaneous material donated by Hemingway scholars; scrapbooks and photos; and nearly 1,200 letters (out of six or seven thousand it is believed Hemingway wrote).

Scholars have used the material to turn out a stream of Hemingway studies. So far, however, they have not seriously revised the going view of his life and work. Instead, they have filled in the crevices of Hemingway’s life story and the major critical lines set out by Carlos Baker and Philip Young.

So far, the major publishing event to come out of the new work has been Ernest Hemingway: Selected Letters. They amply display the writer’s explosive temperament; he often used letters to work off his considerable anger. (One such was written to the Archbishop of New York, Francis Cardinal Spellman, who had irritated Hemingway with an attack on Eleanor Roosevelt. The novelist mentioned he had once been a Catholic — “a dues-paying member” — then said: “The word in Europe is that you will be the next, and first American, Pope. But please disabuse yourself on this and do not keep pressing so hard. You will never be Pope as long as I am alive.”) But the letters also show a Hemingway solicitous of four wives, three sons and a wide range of friends. And they show that despite lucrative forays into journalism, a serious interest in alcohol, and a full life with rod and gun, he worked hard at his solitary craft and never wavered in his dedication to the writer’s vocation.

Some new critical studies have appeared, of course, and by far the best is Scott Donaldson’s By Force of Will. It pieces together a mosaic of Hemingway’s mind through a series of topics (war, sex, money, religion, death) that emerge from his life and fiction. Norman Mailer once noted that a common characteristic of books about Hemingway is that the subject always remains out of focus. That may be true, but it is less true of this book than any other recent one.

Several other new studies have been published which stake out similar claims. Among them:

The Hemingway Women, by Bernice Kert, focuses on his wives and other females who showed up in his fiction (including Agnes von Korowsky, the model for Catherine in A Farewell to Arms, and Lady Duff Twysden, the Brett Ashley of The Sun Also Rises). Kert does not challenge the view that the women in Hemingway’s fiction are generally submissive or manipulative types, but she demonstrates that the women around him in real life — starting with his formidable Victiorian mother — were just the opposite.

Hemingway and the Sun Also Rises, by Fredric Joseph Svoboda, shows how the young writer, inventing from his own experience, labored through many versions of his first novel to fashion his refreshing style. Svoboda recounts Hemingway’s early attempt to tell the story from a third-person point of view rather than from Jake Barnes’ celebrated first-person narrative. And he reproduces material from the novel’s beginning that Hemingway cut out (after Scott Fitzgerald wrote him that parts of the book were “careless + ineffectual”).

Hemingway’s First War, by Michael S. Reynolds, also examines a single novel, A Farewell to Arms. Reynolds uncovers the work’s sources in the author’s World War I experience in Italy, and pursues the revisions in the manuscript. It is a narrow but jaunty piece of scholarly detective work. Even narrower is the same author’s Hemingway’s Reading 1910-1940, and inventory of books the writer owned or borrowed and may have read. (He acquired books at a rate of 150-200 a year, suggesting he wasn’t the “dumb ox” some thought but a self-educated reader of wide interests, including biography, military history, murder mysteries, and — surprisingly — literary history and criticism.)

Fame Became of Him, by John Raeburn, shows how Hemingway the writer became Hemingway the celebrity. For a quarter-century, Hemingway was the best-known author in the world, the first American writer to achieve genuine “star” status (when he took his life, statements of regret came from the Kremlin and the Vatican as well as the White House). Raeburn believes that Hemingway eagerly collaborated in creating his public image in his nonfiction articles and books, by both revealing his private life and reveling in it. At times, he had doubts about his international fame and its effect on his work, but those doubts never caused him to shun the limelight.

Hemingway in Cuba, by Norberto Fuentes, adds new details to the story of the writer’s time on that island, the longest he ever lived in any one place. A Cuban journalist, Fuentes had access to papers and books left in the novelist’s farmhouse and to Cubans who remember him: cockfight cronies and drinking companions, his doctor, cooks and gardeners, and the crews of his fishing boat, the Pilar. The book is badly fragmented, but it does succeed at setting Hemingway against the ordinary life of San Francisco de Paula, where he boxed with neighborhood kids, set off firecrackers at Christmas and sent floral wreaths when a citizen died in the town. After his death a bust, cast from melted bronze pieces collected from local fishing boats, was placed near where the Pilar was anchored. (The boat now rests on the grounds of the Finca Vigia. The rooms in the farmhouse have been left largely untouched. Hemingway’s Royal typewriter is where he left it, a book underneath. Unopened mail lies on his bed. Visitors view the house by looking through the windows, conjuring up as best they can a time when expenses ran $4,000 a month, movie stars were guests, and literary pilgrims came to see, as Hemingway put it, “the elephant in the zoo.”)

In addition to the new scholarly books, A.E. Hotchner’s chatty memoir, Papa Hemingway, has been reissued (with a postscript in which Hotchner keeps alive his feud with Mary Hemingway, who tried to stop the book’s publication nearly 20 years ago). In the spring of 1934 a young would-be writer named Arnold Samuelson hitchhiked from Minnesota to Key West to talk with Hemingway, then stayed on as an indifferent crewman on the Pilar; his memoir of the experience has just been published under the title With Hemingway: A Year in Key West and Cuba. This year Scribner’s is bringing out a new edition of The Dangerous Summer, his account of a bullfight rivalry in Spain in the summer of 1959 — a work that was serialized in Life but never appeared in book form, in part because it required drastic editing.

Hemingway’s admirers have other books to look forward to: more letters, new critical biographies, studies of the journalism and nonfiction, fresh accounts of the formative years in Oak Park and the productive decade in Key West. A television show visiting all the old Hemingway haunts, with one of his glamorous granddaughters as a guide, may be next. The Hemingway revival may be only beginning.

The Hemingway Room closes in late afternoon. As I get off the elevator tourists and schoolchildren are still crowded in the museum store buying Kennedy posters and trinkets. I walk outside and away from the building and then I turn to look back at it, wondering what Hemingway would have made of this resting place for his reputation.

That morning I had seen a cock pheasant and several hens dart from thick sea grass along Columbia Point and cross the road leading to the library. The sight would have pleased him; with game birds around he might not have felt so out of his element in the alien East. Maybe the library and his place in it would have brought him another kind of pleasure. I can imagine him, the competitive juices flowing, nodding at the splendid building with old detractors and long-dead rivals in mind, saying in one of his favorite lines of private irony, “How do you like it now, gentleman?”

Ronald Weber is a former Notre Dame professor of American studies.