Red Smith got Ara Parseghian on the phone to talk business.

Notre Dame had rescheduled a 1974 football game at ABC’s behest. Instead of a routine November weekend road trip to Georgia Tech, the defending champion Fighting Irish would open the season with a Monday night prime-time spectacle in Atlanta under stadium lights and the metaphorical kliegs of national television.

Even back then, the scheduling adjustment did not cede substantial new ground to the economic interests that were staking territory on college playing fields. But it moved the chains. Enough so that the leading sports columnist of the era chatted up the iconic Notre Dame coach about what it all meant.

“The concept of intercollegiate sports as a leisure-time recreation is long out of date,” Smith wrote in The New York Times, recounting his conversation with Parseghian. “But whatever became of the concept of athletics as part of a balanced academic program, the mens sana in corpore sano approach, the notion that the coach is a professor whose classroom measures 360 feet by 160?”

Parseghian, for his part, sounded a little abashed about the external meddling with his syllabus, conceding Smith’s thesis that the University was “wading still deeper into show business, and for nothing but money.”

A 1927 Notre Dame graduate, Smith was a student when the Four Horsemen galloped. He had no illusions about college football’s popularity as anything but the product of savvy promotion. Victory and revenue, he understood, were pursuits of equal importance to the enterprise. The template for winning — and the accompanying windfall — had been pioneered and perfected by Knute Rockne, the coach during Smith’s college days.

As late as 1974, though, Smith could still muster a qualm over college football staging a made-for-TV event. To change the date of the Georgia Tech game, Notre Dame received a $200,000 guarantee (about $1 million today). “Not for the first time,” Smith wrote, “a proud lady has been reduced to taking in laundry.”

How quaint such concern sounds in 2022, when the sport has long since ceased to be a mere Saturday afternoon pastime. Campuses morph into amusement parks on football weekends and millions at home log on to a multimedia extravaganza.

In this environment, nobody needs to be reminded that football programs do not exist just to provide extracurricular exercise for big guys. But the cold water to the face that Smith felt in 1974 still splashes up now and then from the swelling revenue streams: TV contracts, corporate sponsorships, conference realignments, postseason expansion, legalized gambling.

Sandbags had been stacked highest to protect the concept of amateurism. All the money washing over college sports could not reach the student-athletes themselves. For the first time last year, they had access to over-the-table cash flow from the promotional use of their “name, image and likeness.”

That it took so long for players to share in the spoils they help produce speaks to the relationship, at once symbiotic and uneasy, between college sports and money. Over the years, new means of acquiring revenue have generated conflict — sometimes internal to institutions, often between them — over the right to earn and the responsibility to restrain the impulse.

Television appearances once were rationed with the intent of maintaining competitive balance and restricting commercial influence on amateur athletics. In the 1950s, Notre Dame began lobbying the NCAA to relinquish control of broadcast rights so the University could earn compensation commensurate with its football program’s national stature. At the same time, administrators refused bowl invitations and their appearance fees because the timing interfered with studying for exams during those years when Notre Dame’s fall semester extended past Christmas break. Back then, the regular season also determined the national champion, rendering bowl games meaningless to the football program’s ultimate goal.

After the academic calendar changed in 1969 — the year after the Associated Press started factoring bowl results into its final rankings — the Fighting Irish made their first postseason appearance since the 1925 Rose Bowl. As they deposited the $340,000 that major bowl appearances paid in 1969, Notre Dame administrators felt compelled to announce that the money would be earmarked for a good cause: funding minority scholarships.

National broadcast restrictions stayed in place longer, but once those barriers fell and NBC became Notre Dame’s official broadcast partner — a controversial development, circa 1990 — other financial temptations were still considered occasions of sin. When Kevin Guilfoile ’90 responded in this magazine to accusations of greed over the NBC deal, he noted, “If the dollar is now calling the shots in the Notre Dame athletic department, as critics charge, then where are the Gatorade banners in the stadium? Where is the Reebok DiamondVision in the Joyce Athletic and Convocation Center? Why were the Irish the only bowl team not wearing sponsorship patches the last two New Years?”

Certain lines were not to be crossed. Most of Guilfoile’s hypotheticals have come to pass in some form, continuing the natural order of things. This season, Notre Dame dipped a toe into livestreaming with the home opener against the University of Toledo available only on NBC’s subscription service, Peacock. Director of athletics Jack Swarbrick ’76 emphasized that he — not NBC — made that decision, which upset many fans accustomed to free, over-the-air access to Fighting Irish football. He chose the Peacock experiment with one eye on the program’s history and another on its future.

As cable once came to dominate media consumption, streaming is now ascendant and growing “at a rate faster than any of us could have anticipated,” Swarbrick said in October during a livestreamed conversation with Lou Nanni ’84, ’88M.A., Notre Dame’s vice president for University relations. Swarbrick wanted Fighting Irish football at the leading edge of the latest media evolution, as the program always has been. Rockne invited national radio networks to broadcast games for free 100 years ago. Half a century later, Lindsey Nelson — in his loud, quintessentially ’70s blazers — narrated syndicated Sunday-morning replays of Irish games on TV. And three decades on NBC have defined the modern era. Streaming is just the next thing, Swarbrick argues, with particular benefits for Notre Dame.

No longer need coverage be bound to a network’s scheduling. Online, airtime is theoretically unlimited. Peacock provides Notre Dame a platform for extended pregame and postgame exposure, content that fans could watch live or consume on their own time, as often as the spirit moves them.

“Notre Dame is well-positioned in that environment to be programming you want to go see, but we needed to prove it, and I wanted to be first and an early-adopter because that’s what we’ve always done in media,” Swarbrick said. “We were the first ones with a national syndication product — those Sunday morning games with Lindsey Nelson. We were the first ones with our own national contract. And it’s important with that heritage that we continue to be first.”

To be first on the field also demands media adaptability, Swarbrick added. Football independence depends, in his view, on two elements: continued postseason access to compete for championships and a broadcast partner that will maintain the program’s national presence.

As the means of reaching audiences have changed over the decades, Notre Dame’s strategy has evolved in ways its competitors — and sometimes even its own customers — have criticized.

A small price to pay for such a rewarding long-term investment.

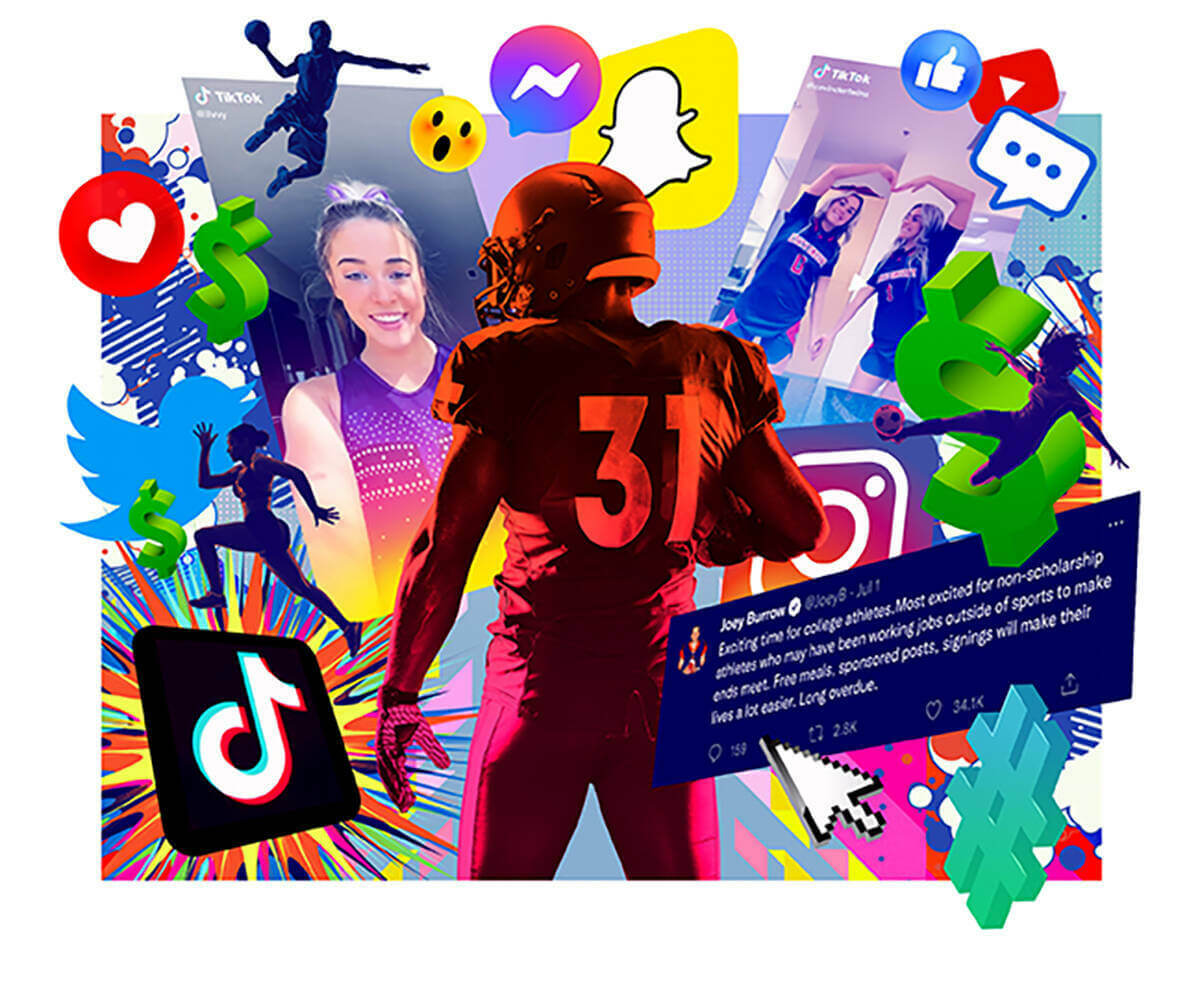

The Impact is NIL

Notre Dame administrators have been outspoken in support for the latest, and maybe most revolutionary, development in the economic landscape of college sports. Swarbrick and University President Rev. John I. Jenkins, CSC, ’76, ’78M.A., have advocated for years to grant athletes the right to make money from commercial uses of their “name, image and likeness.”

In a 2015 Times interview, Jenkins expressed his initial approval of the notion that became NCAA policy last year. College athletes may now sign endorsement deals, hire agents and otherwise form business partnerships based on their sports fame, which previously would have compromised their eligibility.

Though the idea had powerful backers, it did not happen without a legal push. Mushrooming state laws granting name, image and likeness rights pressured the NCAA to institute an interim policy to avoid a patchwork of rules affecting different teams and conferences.

There are still gray areas. The NCAA prohibition remains on direct payments from colleges to players, but schools have leeway in promoting athletes’ name, image and likeness interests. Policies vary. Some limit the kinds of products that athletes may promote. Others forbid using university trademarks in endorsements.

As recently as 2019, NCAA president Mark Emmert called the notion an “existential threat” to college sports. It’s been only about six months since the fetters came off, but so far everything seems fine, existentially.

For a possibly surprising group of beneficiaries, existence has improved. Big stars at major programs were expected to reap name, image and likeness rewards — and many have, like Notre Dame safety Kyle Hamilton. He pitches Rhoback casual apparel and healthy meal delivery from Factor and hosts “Inside the Garage” with teammates Cam Hart, K.J. Wallace and Conor Ratigan on sports personality Colin Cowherd’s podcast network. But the wealth has spread to less-heralded players and stars in nonrevenue sports with large social media followings.

In fact, posting promotional content on social media amounts to almost 90 percent of what college athletes do in return for name, image and likeness compensation, according to data compiled through September from the sports marketing firm Opendorse.

LSU gymnast Olivia Dunne’s popularity on TikTok and Instagram precedes, and probably still exceeds, her athletic fame. Dunne started using social media as a 10-year-old to connect with friends while she was traveling so much to train and compete that she had to be homeschooled. Analysts estimate that Dunne, with more than 5 million followers, could be commanding seven figures to promote clothing brands, a performance nutrition company and a study aid.

Haley and Hanna Cavinder play basketball at Fresno State. Their 3 million TikTok followers pushed them toward the front of the name, image and likeness line, where the twin sisters signed with cellphone and nutritional supplement companies.

Every female varsity athlete at Florida Atlantic University received an offer from the NHL’s Florida Panthers for cash, tickets and merchandise in exchange for in-person appearances and promoting the Panthers on social media. Those who generate the biggest response will receive a bonus.

Still, sponsorships for athletes in nonrevenue sports are the exception. Football and men’s basketball players attracted more than two-thirds of the endorsement money in the first three months after deals began on July 1, Opendorse reports. Women’s volleyball, basketball, and swimming and diving round out the top five. Among Division I athletes across all sports, the average haul from name, image and likeness deals stands at $391.

Because the demands of modern college sports make working campus or summer jobs all but impossible, even such modest compensation can have a meaningful impact. Former LSU quarterback Joe Burrow, the 2019 Heisman Trophy winner and No. 1 pick in the 2020 NFL Draft, predicted as much on Twitter when the new rights took effect. “Most excited for non-scholarship athletes who may have been working jobs outside of sports to make ends meet. Free meals, sponsored posts, signings will make their lives a lot easier.”

Sports talker Doug Gottlieb, who played basketball at Notre Dame before transferring to Oklahoma State, doubted that. “Who is going to pay money to a non-scholarship athlete for name, image and likeness?”

Built Brands, for one. The Utah-based protein-bar maker paid tuition for all the non-scholarship football players at BYU. Most deals pale in comparison with de facto full-rides for walk-ons, but even the often-overshadowed grunts are getting in on the action. Notre Dame’s offensive line, as a group, endorses two restaurant chains, an apparel company and a toilet paper alternative marketed to men.

Some of the partnerships have nothing to do with sports per se. Alabama freshman defensive back Ga’Quincy McKinstry received an endorsement before playing a single college down, based on his longtime nickname. Old-school avatar Nick Saban, the Crimson Tide coach and Aflac spokesperson, must approve of this arrangement because the Alabama roster now dispenses with the cornerback’s given first name, identifying him only as Kool-Aid McKinstry. He’s not alone in benefitting from a beverage-related nickname. Notre Dame long snapper Michael Vinson, known as “Milk,” signed on with the Indiana chapter of the American Dairy Association.

Not all the deals have worked out as hoped. Clemson quarterback D.J. Uiagalelei’s performance did not live up to the hype that Dr. Pepper bought into for the most visible endorsement in the infancy of name, image and likeness rights. Ineffectiveness and injury also compromised smaller-scale promotions featuring quarterbacks Spencer Rattler of Oklahoma and D’Eriq King of Miami.

Will such stories become cautionary lessons, chilling future investments in college athletes? Maybe. Even asking the question exposes an economic disconnect at the heart of college sports. A few players not living up to advertisers’ expectations may raise doubts about what the market will bear, while the long history of failed coaches has not restrained what schools will pay them to go away.

Putting Paid to Amateurism

College athletes still cannot be paid as employees of their schools. Many coaches, on the other hand, continue to draw paychecks long after they have been asked to leave.

In November, ESPN published a “dead money” database documenting the compensation public universities dole out to former football and men’s and women’s basketball coaches. Between January 1, 2010, and January 31, 2021, it added up to $533.6 million.

Will Muschamp has received a combined $19.2 million after failing to make the Florida and South Carolina football programs national powers. Notre Dame gave ex-coach Charlie Weis ’78 nearly that much, spread over several years after his final season in 2009. And former Notre Dame assistant Charlie Strong got $10.1 million in severance after three losing seasons as head coach at Texas, plus another $1.7 million golden parachute from South Florida.

If ESPN’s dead-money accounting had extended past January 31, that $533.6 million tally would have been even higher with recent buyouts at Washington, LSU, TCU and Texas Tech, among others.

Ed Orgeron, who led LSU to the 2019 national championship, reached a separation agreement with the school worth $16.9 million, and the program still offered upwards of $9.5 million a year, plus incentives, to lure Brian Kelly away from Notre Dame. Kelly, who had the Fighting Irish in title contention four times in 12 seasons but never crossed the ultimate threshold, replaced a champion in Orgeron and commanded a salary comparable with that of seven-time winner Nick Saban.

Lincoln Riley made a similar move the day before Kelly did, leaving Oklahoma for USC and an estimated $10-million-plus salary, establishing him for the moment as the highest paid college football coach.

Riley’s new employer also kicked in the $4.5 million to buy out his Oklahoma contract, NBC Los Angeles reported.

What do such riches cascading over an endeavor meant to complement a college education say about society’s priorities?

Such extravagant investments intensify expectations on coaches, which in turn increase demands on athletes, fueling the debate about their access — or lack thereof — to the tsunami of money washing over the sport. Scholarships might have seemed sufficient decades ago when summer jobs were feasible and the time commitment more seasonal, imposing far fewer physical and mental demands. Competing at the highest level has turned into a year-round, full-time job, one that the general counsel of the National Labor Relations Board wants to codify as employment.

Jennifer Abruzzo issued a memo in September saying that college athletes are entitled to protection under the National Labor Relations Act. The memo changes nothing in legal or practical terms for the moment, but Abruzzo’s views reflect the evolving perception of college sports. As recently as 2017, the NLRB denied a request from Northwestern football players to unionize so they could negotiate for pay and benefits. Public opinion and policy have shifted since. According to the 2019 Seton Hall Sports Poll, 60 percent of Americans believe athletes should be allowed to profit from their name, image and likeness. As for schools paying athletes as employees, another Seton Hall survey found that 60 percent of respondents considered scholarships sufficient — a figure down more than 10 percentage points in four years.

Just before the new name, image and likeness rights took effect last summer, a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court in NCAA v. Alston said limiting compensation to players violated antitrust law. The ruling applied only to education-related benefits, such as subsidized tutoring or internships, leaving in place the NCAA’s right to cap other pay and benefits for athletes. In a concurring opinion, though, Justice Brett Kavanaugh challenged the tradition of amateurism itself, arguing that “nowhere else in America can businesses get away with agreeing not to pay their workers a fair market rate on the theory that their product is defined by not paying their workers a fair market rate. And under ordinary principles of antitrust law, it is not evident why college sports should be any different.”

Kavanaugh acknowledged that the court’s ruling could open the door to complications arising from universities one day paying college athletes as employees — how to maintain competitive balance between haves and have-nots, for example, or compliance with Title IX, the federal law mandating gender equity in educational opportunity. To address those issues, the justice suggested, schools and athletes “could potentially engage in collective bargaining (or seek some other negotiated agreement) to provide student athletes a fairer share of the revenues that they generate for their colleges.”

Statements like those from the Supreme Court once would have been unthinkable. Now the words register as just another piece removed from the teetering Jenga tower of amateurism.

Through it all, college sports as a product continue to attract audiences, as they have through decades of changes perceived as apocalyptic to their popularity. It’s that enduring success, always elevating the competitive and financial stakes, that drives the debate about how to divvy the wealth.

What do such riches cascading over an endeavor meant to complement a college education say about society’s priorities? In effect, that’s what Red Smith was asking Ara Parseghian in 1974, an academic question raised before and since with every new revenue-producing innovation or gaudy upgrade in the facilities arms race. But once popularized, each change has become an accepted part of the game, as fundamental to winning as the forward pass. The notion of coaches receiving $100 million contracts to leave one blueblood program for another — à la Brian Kelly and Lincoln Riley — is only the latest example of runaway inflation raising questions about the sport’s sustainability.

As Notre Dame’s Swarbrick addressed the media after Kelly’s sudden exit, a reporter wondered what the big-money musical chairs indicated about the state of the game. The athletic director didn’t have an answer but said, “We better be asking what we want college football to be, and how we make sure it still fits inside a university environment.”

Then Swarbrick went about the business of searching for a new coach, promising the resources necessary to compete for a championship.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.