Can’t we do better?

I was born in 2002, in post-9/11 America. September 11 has always been a day of remembrance. I have never seen a September 11 that wasn’t 9/11.

I have never lived in an America that was at peace. We went into Afghanistan before I was born and exited the country during my freshman year of college. We’ve declared wars on drugs, and wars on poverty, wars on the border — and we’re starting to declare wars on each other.

Older folks always talk of the unity Americans felt on September 12, 2001. A national tragedy transcended political beliefs. On that day, we were all Americans. There has been no day like that for me. There has been no day when we’ve been truly united since then. There’s been no day where we all said, “What can I do?”

“Tomorrow” has always been the implicit promise of American politics. We’ll fix things in the next Congress, after the next election. Tomorrow’s generation will be better. Tomorrow’s America will be more respectful, more understanding. Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.

The Book of Exodus teaches of the plagues the Lord sent to soften Pharaoh’s heart so he’d release the people of Israel from slavery. A plague of frogs overwhelmed Egypt. Frogs were everywhere: beds, kitchens, crop fields, the servants’ houses, the pharaoh’s palace. Finally, Pharaoh says, OK, your people can go if you remove the frogs. Moses asks, “When would you like me to do that?”

With each new plague, Pharaoh says what I think is one of the craziest-slash-dumbest things in Scripture. “Tomorrow.” Release them tomorrow. We’ll sit with the plague one more night.

What the hell?

But we have done the same thing in American politics. We have decided that tomorrow we will be better.

I don’t trust that plan. I thought our generation would figure it out. I thought we would do things differently. I thought our generation would avoid the nastiness that has soiled those who came before us. But we are falling into the same trap. We choose to be right, we choose to go viral, we choose our egos.

The day before the 2022 election, an adviser was expressing frustration about the divisiveness of our politics, lamenting that we were too dependent on our own echo chambers — Republicans reading The Wall Street Journal and watching Fox News, Democrats reading The New York Times and watching CNN. It was horrible.

Because I’m a bit of a jerk, I asked, “What do you do to break through your echo chamber?”

“Well, I can’t read conservative news, I just won’t do it.”

I thought, So it’s everyone else’s problem but not yours?

This isn’t the path forward. If you want to blame someone for the divisiveness of politics, look in the mirror. It’s my fault; it’s your fault. But we can avoid the trap. We can choose to work through our divisions toward unity. To give up the need to be “right” and paint all opposition as “wrong.” To identify the values we share and build a political future around those ideals. To give up doing the same old, same old.

I still believe our generation will lead America toward a better way, but it won’t be easy. It will take active listening to those we disagree with, valuing productive dialogue over point-scoring demonization. Recognizing that is the first step we must take to lift the country out of the rhetorical muck.

Sam Coffman is a junior American studies major with minors in journalism and public service. This essay is adapted from an address he delivered in Professor John Duffy’s Great Speeches course.

You know what I really hate? Time. How time passes. How the more time passes, the more I am filled with regret. Did I spend my weekend well? Could I have worked more? Worked less? Could I have been more “in the moment” with my friends? What about when I go home? Do I cherish the time with my parents? Or do I let my worries or ambitions cloud my mind, so that time passes too quickly?

Sometimes my mind churns because I’m afraid I am wasting my time, my days — the precious present — with things that don’t matter. That one day I’ll wish I had partied on that Saturday night as opposed to doing homework. I fear I don’t cherish being home enough, for that one visit could suddenly be the last time my whole family is together.

I guess time passing makes me more cognizant that I don’t just want memories, I want memories that matter. — Caitlyn McHenry, senior

Letting life be life

These lines of poetry are etched into my grandfather’s gravestone:

Do not stand by my grave and weep,

I am not there, I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow.

I am the diamond glints on snow.

I am the sunlight on ripened grain.

I am the gentle autumn rain.

Do not stand at my grave and cry;

I am not there. I did not die.

Adjacent to the east is the church where many of my family members have been married, baptized and eulogized. Directly south is the farm where my Uncle Matt and Aunt Jeanie live. Where my father’s cousin and my mother’s best friend grew up. Next door is the homestead of my Aunt Blair and Uncle David, the farm where my grandfather was born, the farm with 50-foot barns I spent a summer painting on 40-foot ladders.

Next to that farm is my family’s farm, established 1849, where I got lost in the cornfield, ears higher than my eyes, when I tried to follow my father to the wetland; where my feet were bitten by many a fish in the pond as my legs dripped off the edge of a Styrofoam raft; where I collected wild berries that my grandmother would craft into irreplicable red and blue pies with Crisco crusts.

My grandfather wanted a simple legacy. The poem says just as much about who he was not as who he was. He wanted not to be the soldier, the surgeon, the CEO, nor the pianist, the painter, the poet. He wanted to be the rain, the rock, the river; the grain, the gust, the ghost of things we have yet to lose.

I do not want to romanticize this man. Though he was quite jovial, he had a temper and could be brusque on occasion, and we likely would have disagreed on many political issues. But he knew something that could save many others. He knew how to love a simple life.

What does that mean?

It means to disconnect from systems and connect to people. It means to deconstruct the barrier between yourself and your environment. It means to find meaning outside of the lust for accomplishment or affirmation, and to find few things other than character and Cola truly desirable. It means, as the poet Morgan Harper Nichols writes, to “let July be July” and “August be August,” and to look at the sky and identify the time of day without a thought of the clock.

I wonder what will be my rain, my rock, my river; my grain and gusts and ghosts.

Perhaps mine will be the ray of sun you bathe in on a crisp day, the oak leaves that crunch beneath your feet on an autumn run, or the black-eyed Susan: a reliable, sunflower-like bloom that my father could never remember telling me the name of a hundred times prior.

Perhaps mine will be the compass plant, leaves orienting north, or the goldenrod, with a conservation coefficient of seven, the bergamot you shake in a jar to collect for tea, or the white ends of the honeysuckle leaves that taste more fragrant than any honey in a jar.

Perhaps mine will be the ivy clinging to the crumbling brick, the sand and clay of Adam’s Ridge, the peaches that the bugs always beat the people to on the trees my grandfather planted, or the age-old bullets and pottery shards for which we spent hours mining in freshly plowed fields.

But I, not unlike many of my peers, experience barriers to achieving this so-called simple life.

I, too, fail to disconnect from the “the world of men and money and power” that David Foster Wallace says “hums” merrily along. I, too, have trouble deconstructing the barrier between myself and my environment. How can I step out of my internal space as an organic, asymmetric, sometimes unkempt individual to connect with an external reality that is well-planned and well-maintained, rigid and starkly manicured? I, too, struggle to find meaning outside of categorical desires when my mind lusts for culture and my culture lusts for competition.

I, too, have difficulty letting July be July and August be August. We no longer leave school when the harvest comes. We work the same job, rain or sun. We study when we are sick, and we post celebratory photos when we are sad. We fight to lose weight or gain muscle, and we drink not to feel but to not.

An Appalachian pastoral letter reads, “You cannot save what you don’t love, and you cannot love what you don’t know.” To save your simple life, you need to love it, and you cannot love it if you don’t know it.

Maggie Lenhart ’23 majored in economics with minors in sociology and data science. She is from Defiance, Ohio.

I feel like there is no time to slow down. If I did, everyone around me would be getting ahead. — Estela Ralston, junior

To be Peruvian

Home is the faces of my parents as they wake up and the smiles on their faces as they speak; the sidewalk-sweeps at dawn and the charm of early-July fog; the smell of grilled onions mid-sauté and my brother’s complaints about their flavor thereafter.

Home is the injustice, the guilt and the sorrow of being.

To be Peruvian is to grow comfortable with ever-growing deficiencies: corruption scandals involving the latest political messiah and Andean communities wracked by bleak weather, chart-topping illiteracy rates and demoralizing COVID-19-related deaths. Most disheartening is how these deficiencies belie our renewed pride in our abundant cultural heritage and the cosmic topography of our canyons.

To be Peruvian, in that sense, is to come to terms with the antagonisms that make up our identity, to downplay prospective progress, to breathe a sigh of resignation when faced with any deficiency in our streets and valleys, and to take solace that the next one might be less bad.

Although I would like to claim that distance has yielded perspective during this first year of my studies in the United States, allowing me to find hope in that aforementioned pride, I cannot. With the inauguration of its sixth president since 2016, my country has been thrust into an unprecedented political crisis — dozens of civilians killed and hundreds injured since December 2022 — alongside an inability to mitigate the problems of warming water, torrential rains and floods. Sigh of resignation, indeed.

If my generation is to side with fatalism, passivity will prevail; the injustice, the guilt and the sorrow of being will triumph. Although I have failed to find hope, it would be foolish of me to stop believing altogether.

In Peru, to believe is to revolt. Believing in the prospect of change shortens the distance between current deficiencies and future solutions.

To be Peruvian is ultimately to act out of quasi-irrationality, to hold beliefs without always having enough evidence to support them, to take continuous leaps of faith in our institutions and ourselves.

Home is the faces of my parents as they wake up and the smiles that adorn their faces as they speak, alongside the injustice, the guilt and the sorrow of being. To be Peruvian is to come to terms with the antagonisms that make up our identity and to long for change out of love for our streets and valleys. To be Peruvian is to love, passionately and irrationally.

Marcelo Guzman is a sophomore from Lima majoring in economics and Spanish.

Outsmarting smartphones

A few weeks ago, I came across a blog post about one writer’s experience trading in her smartphone for a dumb phone. She raved about the freedom she won through rejecting modernity: By throwing away diversions such as Snapchat, Apple Music and BeReal, she calmed her anxiety, revitalized her lagging attention span, fixed her insomnia and almost mystically deepened her relationship with God.

I wish I’d scoffed as I read it. Or muttered under my breath that her dumb phone probably helped her shed 15 pounds, too. But, like many gullible 20-somethings fretfully hoping for the next new thing that will transform their lives, I became enchanted by the thought that maybe I, too, could cast off my iPhone in favor of an ancient, Bluetoothless simplicity. Maybe I, too, could experience the beauty of a life where connection with others was untainted by a touchscreen interface. Maybe I could root out everything wrong in my life by pulling up the giant weed of smartphone reliance. I began to crave a smartphone-free existence as the path to the Good Life, or at least a life free from the tyranny of constant notifications.

To echo the ubiquitous refrain, we are more connected than ever; miracles of technological togetherness abound. Yet, as many an op-ed columnist has complained, we feel so intensely lonely. This is especially true among us 20-somethings: we desperately want “inner peace,” knowing that our modern lives are antithetical to that desire. Minimalism exemplified by tiny houses and dumb phones has become something of a philosophical fad for those of us who can’t shake our attachment to technology — or, rather, the guilt that comes with it.

Nothing has really changed when it comes to our human desire to just be better than we were yesterday. We want our finger on the cutting edge of our own age, but, as soon as that edge draws blood, we’ll sheathe it in favor of the best of the past.

After a week or so of obsessing, I realized I can’t throw away my smartphone. For one thing, I can’t navigate to more than two places without the help of GPS. For another, I’d feel even lonelier without group chats to offer options on a Friday night. The list of dependencies runs longer than I’d care to admit, even with all the virtues of connectivity.

So, for now, I’ll still monitor my weather app and ask Siri what song is playing. I may be forced to own a smartphone, but I’ll commit to finding new ways to outsmart it. Our smartphones are neutral parties in our search for meaning with which we must carefully negotiate. There must be a path to virtue in every era that embraces the present instead of rejecting it.

I’ve decided to leave my phone on Do Not Disturb. Maybe that’s modern-day mysticism for you.

Ella Wood ’21, ’23M.Ed., teaches English language arts at St. Joseph Grade School in South Bend.

The harsh blue light reflecting from my computer strains my already tired eyes. I take my final sip of Red Bull and set it next to me, hoping only that I’ll finish in time not to need another one in the morning. I spend my semester jumping from assignment to assignment, week to week, telling myself each time something will change. But it’s almost comical at this point how it never does. And so at the end of each semester, my roommate tells me, I always get sad. It’s the stress, she says. But I don’t think it is. I think it’s the feeling, deep in the back of my mind, that I’m afraid to confront — that none of it really mattered. — Emma Ackerley ’23

Getting real

“How are you f----d up in your life, Jake?”

The question, which caught me off guard during the strangest and most important job interview of my life, is one I believe most people in my generation grapple with.

I was interviewing through the Jesuit Volunteer Corps, a post-graduate service program, for a position as the assistant Catholic chaplain at the maximum-security California State Prison-Sacramento. Some aspects of the role were things I expected: I would help lead Catholic communion services, accompany the Catholic chaplain on cell visits, facilitate spiritual and restorative-justice programs and eventually form my own chapel groups.

As a cradle Catholic who majored in English and theology and had ministry experience, I felt capable. But what I didn’t expect — yet deeply desired — was the job’s call for radical honesty, vulnerability and authenticity, all of which was encapsulated in that interview question. And at first, I got the answer wrong.

I forget what I said in response, but in the middle of whatever incoherent, all-too-thoughtful answer I was giving, I was cut off.

“Jake, stop,” one interviewer said. “You must have said ‘I think’ at least 30 times just now. Try again, and this time speak from your heart. Let yourself feel something and speak to that truth.” Already feeling dreadfully unprepared and anxious from the abrasiveness of the initial question, and now embarrassed I was flunking the test, I had no idea what I would say next. This was a job interview, wasn’t it? I needed to impress, right?

I took a couple of deep breaths and decided my only way out was through. My answer was slower, and I let myself appear unpolished and vulnerable. I’ll never forget what I heard then.

“Yeah, that’s better. I can feel that. And that’s what you need to do inside those walls. That’s how few layers of bulls--- there are there. There’s no time to be anybody but yourself.”

My years of academic reading, writing and resume-building had largely served me well. They opened doors, and I’m forever grateful for those skills. And while learning how to think, I received solid faith formation, which pointed me in the right direction. I also made the best of friends, who continue to support me, along the way.

However, I was often too much in my head. I had too long led with logic. I had put my self-worth in having the neatest, cleanest theology and morality and in presenting myself as the most insightful, composed person I could be. Chief among my sins was thinking that I could fit God inside my head and that being close to God consisted primarily in appearing perfect in faith circles.

After that interview, I noticed a lot of walls I had built within myself. I now wanted to dismantle them to make more space for God and to find myself with God. And from the beginning of my year of service last August, I worked to do so. Or rather, God worked on me through the people I encountered in the prison.

Whenever I hear stories from the people incarcerated there, my heart grows, and I am challenged to inhabit myself more authentically. People have shared with me struggles and secrets they had never told anyone else. I’ve been present to prisoners as they learned of the deaths of family members. I’ve heard countless stories of the pain, trauma and abuse that many incarcerated people have suffered. Through all these experiences, people have shown God to me in ways more beautiful than I could have expected, mostly by opening their hearts, owning their stories and telling them honestly and vulnerably. In other words, by radically being themselves.

Desires for authenticity, vulnerability and honesty lie deep in the hearts of people of my generation. Many of us hunger for what’s real, and it seems to me that people too rarely break through their shame and societal expectations to become the best versions of themselves. I’m grateful to be learning to do so from such great teachers.

Jake Theriot ’22 is originally from New Orleans and this fall will enter the graduate program in social work at Loyola University Chicago. He hopes to continue working with people affected by incarceration.

Faith replaces patriotism

In his 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man, the political scientist Francis Fukuyama prophesied that the Cold War’s conclusion would usher in a Western liberal world order as the destiny of all human government. Instead, my generation is marked by the crushing recognition that technocrats and globalization will not save us from the human condition. Past confidence that Russia and China would adopt Western ideals now seems woefully innocent. The optimism of John Kennedy’s “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech, the Gulf War and the Kosovo intervention gave way to the failed nation-building wars that have marked my entire life.

Rather than the post-history generation, mine is the post-truth, post-trust, post-institution generation. Once-bedrock societal understandings, like the definition of a woman or the validity of our elections, now need to be demonstrated from scratch. Against the backdrop of mass shootings and rising political violence, my father — who grew up fearing nuclear annihilation in one of the infamous South Bronx slums — has confessed he pities his children.

This cultural malaise culminated during my time at Notre Dame. Rocked by a pandemic and an overdue but superficial attempt at racial reckoning, my faith in our country has been shaken. In my youthful patriotism, between speeches at the American Legion and registration drives for the League of Women Voters, I would have told you that America is the pursuit of ideals long dreamed of but never reached. While I still believe that, I am forced to hold that belief in tension with the nihilistic, self-interested, militant America I also recognize. It’s hard to tell whether my country has changed or I have awakened to what it’s always been, but where I once campaigned through my hometown with admonitions of “if you don’t vote, you can’t complain,” I now stare dejectedly at ballots I leave blank.

I am not alone in feeling lost and weary. The most liberated generation ever, we are also the most depressed and lonely. In our freedom, we have created a society in which no social institution can survive because we must deconstruct every perceived social construct, until nothing is left but ever-greater, evermore-daunting freedom.

Thankfully, while the world humbled my patriotism, my education sharpened my faith. At Notre Dame, I traded in my vaguely moral Deism for an honest Catholicism. In part, it was my deepening faith that drove me to question the American outlook. Where I once reticently accepted poverty as an inevitability in an unrealized world order, I now feel much more viscerally the cries of the poor, and I reject more harshly a culture and economy that ignore them. Ironically, my cynicism toward our system has afforded me an optimism for our historical moment — albeit a sober one.

Just because we are not progressing toward the utopia we imagined this century would bring does not mean we have hit a low point. C.S. Lewis dubbed the idea that we should expect the future to rise above the past “chronological snobbery.” Our world is not coming apart at the seams, about to break: It is already broken, and it always has been. Just as the future is not something to worship, the past is nothing to long for.

Despite the global chaos of my college years, I am hopeful. My belief that justice and peace will prevail, which once resided in my unjaded patriotism, lives on in something more ancient and battered than America. It lives on in the Church that, unbeknownst to the news media, is not dying or even shrinking; the Church that transcends language and time to offer a place of rest for the lost and weary.

Weeks before COVID-19 sent us home during my junior year, a fellow student died. As I walked back to Cavanaugh from my campus job late on that winter night of her memorial Mass, a somber hymn pulled me toward the overflowing Basilica, where I stood outside, straining to hear the priest’s final remarks. It is in that moment, singing the closing song of a Mass I did not attend for a woman I never met but often think about, that I place my hope. It was there, at a church dedicated to the true Mother of Exiles, singing “Christ Be Our Light” in the cold and bitter darkness, where I first felt the weight of the Congregation of Holy Cross’ motto: Ave crux, spes unica. Hail the cross, our only hope.

Sophia Sheehy ’21 majored in economics and applied math and minored in constitutional studies. She is a federal civil servant and lives in Arlington, Virginia.

How hard could it be?

“I want to go to medical school and become a doctor.”

Well, that’s what I thought. Ever since I was a young boy, this has been my goal. “It’ll be difficult, Nadim,” I was told. “You’ll lose the peak years of your life, because you’ll still be in school.” I was unmoved, unassailable, because I didn’t care about such precautions.

Looking back, I was naïve. I didn’t know what I was getting myself into. All I could think about was being a doctor, not the arduous journey of becoming a doctor. I told myself, “You’ll be fine. How bad could it really be?”

I now know the answer to that question: really bad. I never have time to relax, to enjoy my college experience, to live even a somewhat “healthy lifestyle.” Often I don’t eat because I’m working. Often I skip time with my friends or a workout because of an upcoming exam. Now, don’t get me wrong, it’s not that I procrastinate. I am actually a responsible student who tries to work ahead. But it always seems I have one more thing that I have to get done.

“Dude, how are you still doing homework?!”

This is a question I hear far too often from friends who aren’t pre-med students. My answer is always the same: “The grind never stops.” I say it with a determined and somewhat sardonic tone. My friends seem convinced that I have it under control. But the truth is it always feels like chaos is looming. Professors assign work as if theirs is the only class students are taking. The pressure is perpetual and, above all, self-inflicted. I’m here at Notre Dame because my standards are high.

Technically, I haven’t even started the hard part. I haven’t taken the MCAT or applied to medical schools. And although I haven’t faced those stressors yet, I’ve experienced doubts. It seems inhumane to say I’m putting myself through this process even though I can admit I don’t like one second of it. But it’s a means to an end: I want so badly to be able to help people, to save lives, to treat them with care and respect. The idea that one day I might heal people and create a connection with them keeps me going.

Ultimately, it is up to me to decide what I want to do in life. I often ask myself, since when has something so good ever come easy? And when times get unbearable, it is God who lifts me up and pushes me through.

Nadim Khouzam is a junior from Memphis majoring in neuroscience and behavior and minoring in Middle Eastern studies.

A different generation

Last summer I worked as an intern with Alzheimer’s Orange County. One part of my job was community outreach to increase awareness of the disease, but a more significant — and more challenging — responsibility involved working with elderly patients in the adult day center. Many of the people I worked with had difficulty remembering my name, what they ate for breakfast or even where they were at any given moment. Some patients had aphasia or Parkinson’s disease, rendering verbal communication impossible at times.

A patient I’ll call Dennis had late-stage Alzheimer’s. The damage to his brain was so severe that his words were effectively incoherent. One week, we organized a prayer service for patients like Dennis and their caregivers. As I ushered guests in, I spotted Dennis waiting in the vestibule. Despite his calm demeanor, I sensed fear and uncertainty in his eyes. Instinctively, I walked over to him, grabbed his hand and started singing the entrance song. After a few minutes, I was amazed to find the biggest smile spread across his face as he started to sing the Mass songs with me. Later I learned this was the first time he had verbalized anything in weeks.

Dennis taught me that young people have a tremendous capacity to make a difference in this realm. By advocating for music therapy sessions, quality healthcare or counseling for caregivers, we can help alleviate the suffering of the older population. I learned, too, that little things matter just as much. In providing companionship, showing compassion and celebrating the last years of life, we can create moments of peace and lucidity in a person’s day.

For all of Generation Z’s calls to arms over equity and inclusion in race, gender, mental health and affordable education, we must not forget our elderly. There are currently 56 million adults aged 65 and older in the United States. Projections exceed 96 million by the year 2060. We should hope these additional years are spent in joyous productivity. Unfortunately, most older adults spend their latter years alone and suffering from chronic diseases. An estimated 6.7 million elderly people in the U.S. live with Alzheimer’s or dementia.

My mother shared with me a quote from Mahatma Gandhi: “The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members.” The aging population is vulnerable, especially when they cannot advocate for themselves. The onus is on us. As Gen Z strives for inclusion, let us remember equity cannot be selective.

Aidan Rezner is a junior from Orange County, California, majoring in neuroscience and behavior and minoring in compassionate care in medicine.

We are the last generation born before the advent of the smartphone. I remember marveling when my father brought home his first Blackberry. I wasn’t old enough to realize how revolutionary it was. When I turned 14, it wasn’t hard to recognize when the toddlers I babysat had no imagination.

“When will you let us watch YouTube?” they begged. After hours of compulsory hide-and-seek, I was having more fun than they were. Not even fort-building could light up those young, bright eyes. There was nothing that could flicker excitement like watching someone else play a video game. I had to quit. I couldn’t stand to watch.

“Will you give your kids access to phones and tablets at a young age?” my friend asks over dinner.

“Absolutely not,” another replies, picking up her phone to respond to a text. — Maggie Eastland, senior

The most powerful tool

The dried-up fountain in the park. Swirls of people. Lives colliding momentarily before returning to course. The cool air, the ice-sharpened words of my friend Erin: If you knew you were going to die early, would it change how you live?

It sounded like a question in a science-fiction novel: You get a call on the day of your demise, telling you of your impending death.

Erin exudes joy and optimism. Her personality envelops all the spaces she enters, and her hopes for the world are bigger than most. She dreams of a job in the U.S. Foreign Service; she wants to spend her life in deep relationships, traveling the world and working toward peace. Listening to her makes me feel optimistic.

Yet for Erin, the prospect of knowing a potential due date on her life isn’t hypothetical. Her mother recently died after being diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s. Erin faces a 50-50 chance of dying before age 50, something she might learn more about from medical tests.

Would you take these tests? If the news was bad, would you live differently? Would we live differently if America or the world had a definite doom date?

My life, like my friend’s, has known loss. I lost my father when I was 8, my mother when I was 12, a friend at 14. I felt angry and left behind by the substances and mental illnesses that took them from me. The funerals, the obituaries, the entire grief process are baked into my mind.

At my mother’s funeral, we sat in clanky, beige, metal chairs in the church cafeteria, tears one moment veering to obnoxious laughter the next. We told jokes and the most embarrassing stories. It was probably the most unholy event that space had ever seen, but that was Mom.

The best grieving represents a person’s life truly. In his novel Speaker for the Dead, Orson Scott Card writes that he “grew dissatisfied with the way that we use our funerals to revise the life of the dead, to give the dead a story so different from their actual life that, in effect, we kill them all over again.”

Our graduating class — 2024 — has grown up during a long, slow death of societal innocence and naiveté. We were born in the shadow of 9/11, matured during the longest war in United States history, hobbled through the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, started high school during an election that upended our politics, and graduated during a once-in-a-century pandemic amid the most impassioned reckoning for racial justice since the civil rights movement. Our optimism comes at a cost, and it has been cooled for many of us by the dark clouds of pessimism we see rolling in from the horizon.

Yet optimism, when grounded in a realistic recognition of one’s circumstances, is the most powerful tool we have to remake the world. My friend Isaac reminds me that “optimism in the potential of humanity has ended wars, prevented democratic collapse and enshrined human rights law. The same spirit has also paved potholes, planted community gardens and opened new schools.”

I find a certain precarity to “progress,” as it has always been episodic and fragile, not inevitable. My generation inherits a legacy from those who came before us in their attempts to push us toward our highest values. We also inherit the task of saving the world from the perils of climate change, racism, economic inequality and other injustices that some of those same people tried to rectify. We don’t move in one direction as a society, and we often stumble while trying to redeem the world around us.

“To realize that olden-timey people were self-contradictory hypocrites is like realizing that bears s--- in woods,” the novelist Zadie Smith writes. “I like to imagine the students of the future asking similar questions about us. Why did we buy iPhones when we knew the cobalt inside them could have been mined by children for subsistence wages? Why did we love cheap clothes when we knew yet more children made them? Why did we buy plastic water bottles, every day, for decades, when we knew they were environmentally disastrous?”

My graduating class and my friend Erin and I have seen our share of storm clouds. Yet our generation exudes optimism. A recent study found that 80-some percent of us believe we will enjoy financial stability and be able to address global challenges by 2030. Our optimism isn’t naiveté. We aren’t blind to the storm clouds. Rather we recognize the frustrations, dangers and darkness that we’ll need to overcome. We are optimistic not despite the challenges we face but because of them.

Dane Sherman is a senior from Seattle majoring in American studies and peace studies with a minor in gender studies.

The weight of the world

“You have eight years. Good luck.”

My biology professor’s words blindsided me. Was it true that my generation has eight years to find a solution to climate change? My classmates filed out of the auditorium. I remained seated. I knew climate change was a dire issue, but that number eight set the “point of no return” much sooner than I had expected.

While the bluntness of the sendoff was jarring, the sentiment was not. I already knew my age group had been passed the responsibility of correcting the environmental mistakes of previous generations. We are the ones who will live longest to see the success or failure of our efforts.

Like many other members of Generation Z, I understand the weight of the problem is much greater than myself, but I do not know what my ethical responsibility is. On the one hand, the climate crisis will only be solved by dramatic political and scientific actions I cannot achieve alone. On the other, I can contribute to a culture of environmentalism, even if the direct impact of my actions is small. The balance — and often imbalance — of these thoughts generates questions: Should I go vegan? Is my career choice helping or harming the situation? Would having children be unethical?

My biggest struggle remains with the environmental impact of starting a family, something previous generations did not have to consider. I have always pictured myself having kids, but now it feels selfish to bring a child into a declining world, or worse, to hand off the problem to them. Am I ethically obligated to sacrifice my desire for a family while larger corporations refuse to sacrifice a dollar? Yet if I do not change my lifestyle, I feel I am not doing enough. Every decision seems to have life or death consequences.

While none of these questions has a clear answer, I realize I am privileged in knowing that I can make choices, no matter how small, to help the environment. I may choose sustainable brands, maintain a plant-based diet and vote for people who prioritize my values. Many in my generation do not have such choices. Society saddles us all with the same guilt and responsibility but different consequences, as impacts will be most severe on those least responsible for what has happened.

Older generations have placed us in an impossible position. We are called to enact significant change and use our voices for good. But our votes have little control once elected officials take office. Even when we believe we are electing “green” leaders, their political actions sometimes undermine their advertised goals. For example, the Biden administration’s recent approval of the Willow Project, a proposed oil-drilling operation located on the federally owned National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, contradicts its promises to slash carbon emissions. Drilling will likely begin in 2027, only three years before our climate change “deadline.” More and more, it seems any environmental headway is counteracted in the name of economic progress.

The Gen Z experience has been marked by countless “once in a lifetime” weather events, increasingly unpredictable seasons and rapidly rising ocean levels. As we continue to watch events unfold, it becomes harder to hope we can reverse the effects of climate change.

When my professor wished us “good luck,” we had eight years to reverse the climate crisis. As I write this, we have seven.

Maria Murphy is a senior majoring in applied and computational mathematics and statistics with a concentration in biology. She is from Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania.

Off ramp

After five years as a seminarian, I left the formation process to give more time and attention to academic philosophy. It might not seem as worthy a calling as priestly ministry, but philosophy ignites my passion — not just because I enjoy it, but because I believe it can improve our lives and communities. When others see my work and the sacrifices I make to do it as nothing more than a fancy waste of time, I feel greater concern about what their attitude means for the world than what it might mean for my career.

I hope to land a tenure-track job or else to slog through whatever postdocs or instructorships I scrounge up while waiting for that offer to come — if it ever does. It might not matter, though, if students and universities decide that, in an age of automated writing and crowdsourced critical thinking, philosophy is better left on the fringes of respectable study. When I chose my major, I was more interested in getting an education than in getting a job, but that seems to have become an uncommon way of thinking.

I must sound horribly out of touch, unconcerned by the real-world pressures and anxieties my students face, but I’m not. Their lives are the very center of my concern, but I reject the idea that they’re best improved by an obsession with employability and economic potential. I want to help students reach for something more important than a strong résumé. I want to strengthen their souls. I want to cultivate communities of good hearts and clear minds.

I thought the value of these things was clear to others, but I have had to reset my expectations for students who come to class motivated more by the hope of getting closer to their degree than of getting closer to the truth.

So, I’ll finish my studies whether or not it’s reasonable to expect a teaching job. I can find a job anywhere, but philosophy improves my character in a way few other things can. Philosophy, at heart, is the love of wisdom, and we seem ready as a culture to cast wisdom aside. If we fail to love wisdom, I shudder to imagine what we’ll love instead.

From Bowling Green, Kentucky, Devin Santiago Dettman ’20 is studying philosophy at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo.

Hauntings

Yesterday I got a Snapchat memory that made me twist. It was a picture I took of the Indiana Statehouse on March 24, 2018, 38 days after a former student of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, shot and killed 17 people there, injuring 17 others.

I was a high school senior at the time. I begged my mother to drive me to Indianapolis to take part in the March for Our Lives that was happening there.

When word of that shooting hit my school, I remember my English teacher pausing class to turn on the news. We were called to the gym for an assembly. After school, I went to color guard practice. Two hours later I was crying in my car. Seventeen people. There were 17 students in my color guard.

After the Parkland shooting, you could only enter my school through one door in the morning. Your bag was searched. You couldn’t carry a backpack in the hallway after 7:30 a.m. We carried our books between classes.

Administrators gave us laminated name tags, the kind you get when you go to a conference or freshman orientation. If you didn’t wear it, you had to go to the office for a dress-code violation. You had to pay a fee if you lost it. We called them our dog tags.

Sometime in the early months of my freshman year at Notre Dame, I was sitting in the dining hall with soon-to-be-friends. We were talking about strange traditions and weird stories from our high schools, defamiliarizing the recent past as if a few months before it hadn’t been as natural as breathing, as if doing so would make us more mature. We were laughing at something when one of my future friends interjected.

“One time there was an active shooter at my high school.”

The table froze and turned. “What? You can’t be serious.”

“Oh yeah, my junior year. We had to duck under desks and do all that. My class was on the first floor, so we all climbed out the window and had to run across the street.”

More silence.

“Oh, but it wasn’t a big deal. No one got shot.”

A few weeks ago, I was substitute-teaching physical education at a school just a few blocks from my childhood home. It was my last day in that job, and after several cold, rainy days, it was beautiful outside. During my last class of the day, kindergarten, I decided I’d take the kids outside. The library teacher had also taken her class out, so a lot of kids were running around and getting into minor trouble. Use gentle hands! Don’t run in front of the swings! Get that out of your mouth! That sort of thing.

I was refereeing a very poorly executed game of soccer when a kid from the other class ran up to me.

“Teacher!” he said, out of breath with eyes full of concern, “Mason said he has a weapon!”

The world silenced around me. “OK. What kind of weapon?”

“A gun.”

“Point out Mason to me, where is Mason?”

Mason was upside down on the jungle gym. I signaled him to come to me, and he did. I got down on his level. I asked him about what he said to his classmate. He denied it. He started crying. He didn’t really have a gun, he said, it was just a joke, a fib.

I don’t remember what I said then. Something about not being able to tell those kinds of jokes at school. I took him over to the library teacher. She called the office. Someone came to get him.

My hometown wasn’t on the national news that night. But I sat up late. Thinking about Mason’s small hands. Thinking about a woman named Abigail Zwerner, the teacher shot and seriously injured by her 6-year-old student at Richneck Elementary School in Newport News, Virginia.

Now I’m teaching English abroad. I’ve only been here a short time, but I have some really promising students. I was talking to one at the bus stop after class, and I suggested she look into some programs for studying in the United States.

“I would love to. It would be great to improve my English, but I can’t.”

“Don’t worry,” I replied. “Most of these programs offer full scholarships. You wouldn’t have to pay.”

“Oh, of course. But my mom won’t let me.”

“Why?”

“She says I’ll get shot.”

From Evansville, Indiana, Alena Coleman ’22 is teaching in Uruguay on a Fulbright scholarship.

International flavors

Toward the end of July, my German roommate, Steve, and I arrived at the apartment we had called home for the year in Bologna’s Piazza Verdi. We had returned from a two-week trip to visit our roommate Carmelo and his family in Sicily — a final escapade to conclude the 11 months we had spent together. That trip had ended in one of the many teary goodbyes I had to make that summer. Coming back to Bologna, I knew I would have to face the hardest of all.

After entering through the solid, oversized wooden door from the street we climbed up the three flights of stairs to our apartment as we had done so many times before. Our bodies aching from the backpacks we had creatively overstuffed to avoid airline baggage fees, we both let out a sigh as we sat down beside each other on the living room sofa.

Upon hearing us return, our roommate Diego, also Sicilian, came out of his room, which was empty except for the moving boxes. For a few minutes, we sat, not speaking, ignoring the presentiment we all felt. Diego broke the silence. “Volete cucinare?” Do you guys want to cook?

It was a phrase spoken countless times during our year together. This time, the finality rang in Diego’s voice. We were the last three left in the apartment, and in the following days we, too, would depart. I would return to Indiana to finish my senior year at Notre Dame, while Steve would do the same in Germany. Diego had decided to transfer his studies to Rome and was heading to a new apartment.

As we brainstormed our last meal together, we couldn’t help but reminisce. After all, the three of us had bonded in the kitchen.

It started with avocado toast. Shortly after moving in, Diego became curious about this breakfast habit and asked me to show him how I made it. This conversation evolved into what I still think was our best invention — a designated weekly avocado-toast day. Italian style, of course: the avocado topped with aged prosciutto and Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese.

Soon we were cooking together regularly. We shared our favorite recipes, an amalgamation of three cultures. We made Diego’s family lasagna and Steve’s grandmother’s beef stew. We hosted Thanksgiving dinner for our friends. Despite the ridiculous amount of work, that meal remains one of my favorite memories of my time in Italy, the first moment I felt truly at home in Bologna. It was a very Italian Thanksgiving, with no traditionally American food other than apple pie, but the spirit of friendship made it feel familiar. And of course, it wouldn’t have been Thanksgiving without an argument about politics. Leave it to Steve and our strong-minded napoletano friend, Tiberio, to decide it was the perfect time for a debate about communism.

As the year continued, we experimented and tried new recipes. We made couscous, carbonara, chicken schnitzel, pizza. By late fall, we had taken on baking. Banana bread, cookies, brownies; you name it, we made it.

Even on the days we were particularly busy or tired, we found a way to scrape together a meal by pooling our ingredients. Sometimes it was as simple as pasta with pesto. Our meals became a ritual of sorts, a way to grow our friendship and connect through the mundane activities of everyday cooking.

After an almost too-intense deliberation, we decided our last meal would be one we had never prepared together: tacos. My mother had brought taco seasoning when she visited over Christmas, yet somehow we had never gotten around to making them. After a quick trip to the supermarket, we had the rest of what we needed.

What ensued was our loudest, most chaotic cooking session yet. Emotions running high, we screamed as we blasted our favorite songs — Italian rap, mainly — and danced around the kitchen with no roommates left to quiet us. I wish I remembered more about the food itself, but as I absorbed this final night together and looked back all we had shared, food was the last thing on my mind.

No longer could we put off the sadness we felt, knowing we would never share another meal in our apartment in Largo Respighi.

Emma Ackerley ’23 studied anthropology, global affairs and journalism and was this magazine’s spring 2023 intern.

Bridging divides

We know there’s a lot wrong with the world today. We know the climate is in crisis. We know the country is plagued with mass violence. We know the pandemic has stolen innocent lives.

Coming into Notre Dame, I saw my undergraduate experience as a time to move out of my sphere of familiarity, to start something new — a chance to ask tough questions about the world and to research the disparities that arise in global health. That was my dream.

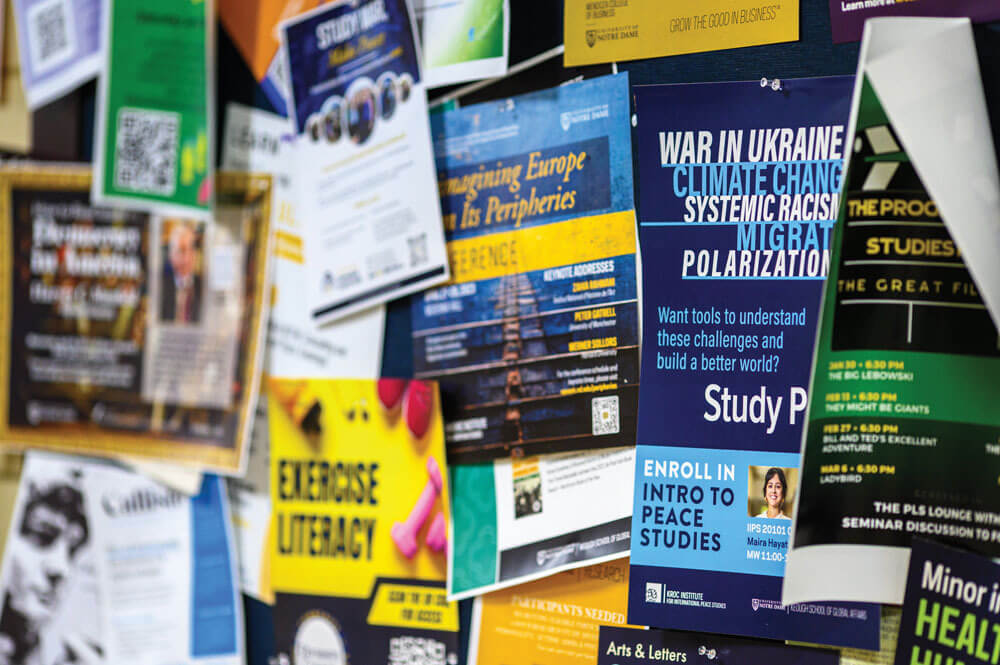

When I registered for my required University Seminar, I was looking for a class that had some relation to health care and would help me understand the disparities that I wanted to solve. I had the passion to become “a force for good in the world,” as promised by the tagline. But what would that really mean?

For my final project in that class, I focused on public health in Benton Harbor, Michigan. The investment was personal. I come from a small, medically underserved town — Water-vliet — not far from the “twin cities” of affluent St. Joseph and impoverished Benton Harbor. I never imagined that 19 years could be the difference in life expectancy between two communities separated geographically by a river — and yet divided by so much more.

I finished my research angry that neighboring communities could experience such drastically different health outcomes. I was disappointed by what we’ve let happen. Public health injustice is not just something we hear about on the news; it occurs right in front of us. And so much is wrong — I knew I couldn’t bridge the health gap on my own. Maybe, I thought, I’m in over my head.

But Professor John Duffy posed our seminar a question — a quote from T.S. Eliot: “After such knowledge, what forgiveness?”

So I took another class, International Development in Practice, to understand how health care may be a “cure for injustice,” and I worked with the global health care nonprofit Partners In Health. That project, emphasizing the importance of empathy, was an opportunity to design solutions to tough questions. I was no longer a mere student with big dreams. I found real meaning in that initial aspiration to be a force for good.

It’s OK to recognize complexities in the world. In fact, it’s crucial that we understand the problems we face. What matters is what we do next.

Leah Brucal is a junior majoring in science preprofessional studies with minors in compassionate care in medicine and poverty studies.

The world’s mosaic heart

I’ve caught glimpses of the human heart as a middle school teacher in Los Angeles with the Alliance for Catholic Education. In a city arguably at the center of American culture, I’ve seen very clearly how we as a society are struggling at the seams of the world, testing new ideas, pushing boundaries, reconciling with the past.

These efforts to make sense of a confusing and broken world seem to stem from one place: our aching human hearts that yearn for another to see us. Not to see us as we appear under the masks we wear. Not as homeless or lost people. Not as wannabes. Not as failing or “troubled” students. But just as we are: humans trying to weld back together the pieces of our broken hearts like artists arranging fragments of stained glass. Only when it comes to the human heart, the pieces are delicate and weighty, and we’re trying to capture an image we can’t quite make out yet.

The world is struggling with its mosaic heart right now. Beautiful oceanfront houses overlook tents pitched beneath overpasses. New hit albums play as police helicopters cross the sky. Satan is celebrated at the Grammys while a Catholic bishop is murdered 20 minutes from our door.

And yet, light gleams through. My students compete daily in our Seventh Grade vs. The New York Times’ Wordle game. Families ask for prayers, and religious sisters invite me to Eucharistic adoration. Students write stories about baking wizards and tap-dancing lions. Beautiful glimmers of hope and innocence peek through these seams of the world we are pushing against. We just forget to pause, look up and let them catch our eye.

Every person aches to be seen. To be given time. To have someone listen to their stories. To have someone celebrate their big and little joys. To have someone pray for them and pray with them. To have someone hold them to high standards and still show them mercy. To have someone look them in the eye and tell them they are not alone.

We may be consoled or disheartened by the state of things, but we must not be indifferent. Our human hearts need an apostolate of authentic presence right now. Responding to this ache means a Eucharistic pouring out of our time and attention, and when we do that, we will find ourselves living our call to holiness, one mosaic heart at a time.

Originally from Raleigh, North Carolina, Julia French ’22 majored in philosophy and in education, schooling and society.

The time is now

I have always felt immense pressure to have my next move perfectly planned. Trying to figure out “what’s next?” can be excruciating — especially when your response to that question is “I don’t know.” Try explaining that to your relatives at Thanksgiving.

Most college students understand the need to have the well-thought-out plan for the next stage of their lives. It follows the pressure to exceed expectations that particularly comes with being a student at a prestigious university.

I fear I sometimes allow these pressures to induce so much stress that I neglect the beauty and opportunity in front of me. It can be easy to forget that this journey is not solely about securing a job but is also an invitation to discover who we are as people. I worry that this need to achieve and have a “next step” forces us to follow one path prematurely, without taking the time to look inward and discover what truly fulfills us.

Notre Dame strives to be a force for good in the world; everyone here wants to make a difference. Maybe the best way to become a force for good isn’t to have the perfect GPA or log the most hours in the library, but instead to find what we are passionate about.

We spend so much time comparing ourselves to our peers, competing for the best grade or internship, that we lose sight of why we are here: to build meaningful connections while making a positive impact on the lives of others.

We should all take a step back and dedicate more time to self-discovery and reflection on our calling — and the values that led us to Notre Dame in the first place.

Mackenzie Kelleher is a junior studying neuroscience and behavior with a minor in science and patient advocacy.