I

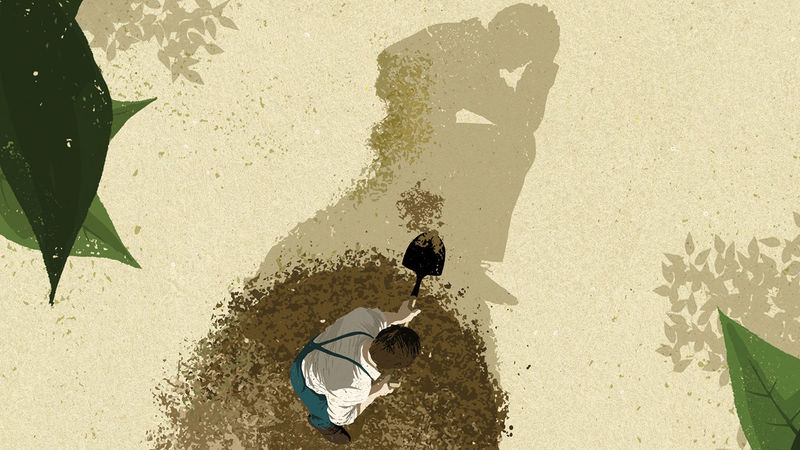

For six months in 1961, I lived with four other men in the “men’s bungalow” of the largest convent in the Diocese of Pittsburgh — the five of us lost, one way or another, among a sea of women vowed to poverty, chastity and obedience. What cast me there in early April, only a few weeks out of a Capuchin novitiate after six years of minor seminary, was a suicidal desperation very much like what Karen Armstrong describes in The Spiral Staircase: My Climb Out of Darkness: “When I looked ahead, the only possible future I could see for myself was a locked ward or a padded cell. My years as a nun had somehow made me unfit for the world, had broken something within me, and now I seemed unable to put myself together again.”

Armstrong fled her convent to survive, but I moved in the opposite direction to avoid my own padded cell. I went to live and work at Mount Alvernia, the motherhouse of the Sisters of St. Francis. Named for the isolated mountain refuge of La Verna in the Tuscan Apennines where Francis of Assisi lived in a cave and, it is said, received the wounds of Christ, Mount Alvernia likely saved my life — and the lives of others in my family, too.

A few days before Sister Gladys hired me, I’d made a bizarre effort to drown in the ice-choked Allegheny River without committing a mortal sin: a suicide without blame, somehow. I couldn’t pull it off. Now, nearly 60 years later, I understand that the biggest source of my suicidal gloom is also what guided me to safety. As another sometime-Catholic writer, Mary McCarthy, has written: “the poison and the antidote [are] eternally packaged together by some considerate heavenly druggist.”

None of this was clear to me then. The form my impulsive suicidal hope took seems especially suited to a goody-goody, overheated Catholic boy — the undeveloped conscience of a first communicant frozen in the body of a virginal 20-year-old.

Here’s what happened: After shedding my brown robes and sandals that February, packing my few belongings and showing up — damned and crazy, I thought, a disgraced failure — at my dangerous family home where there was no room for me, all I could do was pray obsessively, keep trying to make a good confession and imagine writing for the Pittsburgh Catholic.

When my walk-in visit with editor Jack Deedy a few weeks later went nowhere, I gave him a few Fidelians, the award-winning seminary newspaper I’d co-edited, having circled editorials I had written — a denunciation of Mao’s Great Leap Forward and an earnest Christmas op-ed headlined, “Peace to Men of Good Will” — and I left. Deedy had been kind, listened closely, but told me he had no work just then. He would keep me in mind. I was in no hurry to bus back to Donora, my steel-town home where, crowded in with seven younger siblings, I had to sleep in the hall outside the bathroom on a metal bed whose iron posts I’d hacksawed till they fit under the slant of the attic stairs. Better not shove those jagged edges into the plaster. No telling what Dad might do if you gouged that wall.

Instead, wandering Pittsburgh’s Golden Triangle — nothing then like the glitzy tourist showcase it is now — I trudged through the muddy clay, dead weeds and sooty snow around an unfinished construction project and toward the banks of the swollen, brown Allegheny, its waters rising fast. An ice jam had broken upstream; the swirling chunks and floes clinked and sloshed, colliding and grinding on each other from shore to shore. Big branches, old planks, bottles, tins, all kinds of debris streamed by in the swift current. I’d never seen anything like it.

No one was within a quarter mile of me and, mesmerized, I felt this natural drama beckon, pulling me like a magnet, a sudden gift. Could I devise a drowning that would not be a mortal sin? A leap from one of many nearby bridges would be deliberate, therefore culpable, damning me forever. That was out. But walking the concrete steps of the riverbank, the lower ones flooded by churning water and ice, I wondered how I might twist an ankle or misjudge a step. Stumbling, I’d strike my head and slip into the inviting, rising water. Like my father, I was unable to swim and terrified of water. I’d flail in the ice, panic, try to survive, uttering a perfect Act of Contrition, all the while being swept further away. Drowning in the cold Allegheny, I’d be delivered at last from personal darkness into the wider one, waking before the face of God.

But if I hoped I’d fall in and, hysterical, go under, wasn’t I already culpable, committing a sin of the mind? If I succeeded, wouldn’t I still end up in hell? I walked closer to the water’s edge, backed off, weaved in again, a loony, erratic hesitation waltz along the roiling Allegheny. My inferno conscience kept blazing up new rationales, questions, counterarguments and scenarios — endless loops of rumination, none satisfactory. This was the tormented logic of the religious compulsive, but also a nonstop questioning that kept me alive.

In my bottomless hunger for certainties, I could have no suicide at all. My ankle never turned, my foot never slid, the Allegheny flowed into the Ohio without the freight of my young body. Finally, as the late-winter afternoon sky darkened, I slumped toward the Greyhound terminal and the bus to Donora. All I had produced was more grist for the ceaseless grinding of the millstones of my conscience, another serious sin to cough up in agony from my side of the confessional veil, whenever I summoned enough guts to enter that dark little box again.

Yet it was something I’d said in confession earlier that day that would spring me from no-place-to-hide Donora. Before my disappointing drop-in at Pittsburgh Catholic, I’d trolleyed out to Saint Augustine Friary in the city’s Lawrenceville neighborhood, seeking absolution once again from whatever priest was on hand, one of my last attempts at sacramental forgiveness in what I’ve long since recognized as severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. At its height several months earlier, as a Capuchin novice, I’d forced myself to confession several times a day, assailing infirm old Father Athanasius with absurd self-accusations. Horrifying thought: Could my endless scruples actually hasten my confessor’s death? The structure of mind itself was aflame. Every thought and feeling (I could not distinguish the two) was a rebuke. Nothing inside could withstand the white heat of my scrutiny. Everything was a sin — the Puritan Young Goodman Brown of Hawthorne’s short story as Catholic.

Whatever I’d said to the priest at Saint Augustine’s on the morning of my would-be suicide, he’d heard something deeper. The phone rang in Donora a few days later. Father Whoever, OFM Cap., had found a live-in job for me at some convent I’d never heard of. I was to call a number and ask Sister Gladys for details.

Mount Alvernia took the pressure off. Lugging my flimsy suitcase up “Snake Drive” — the long, red-brick, switchback driveway that tamed the hill where the nuns had built their home — I was no 17-year-old Benjamin Franklin entering Philadelphia, clutching his three rolls, confident, ambitious, determined. I just felt safe. Safe from the novitiate terrarium, where every time a scream of conscience drove me to confession or held me back from communion, my evil was on display for all to see. Safe, too, from Dad — a different kind of safe. I’d long mastered his shift schedules at Pittsburgh Steel and knew how to lay low. But I was completely unmoored. Without work, money or a hint of a plan, I would soon have appeared in his crosshairs for a night of drunken terrorizing.

“You’ll live over there in the men’s bungalow,” Sister Gladys said, pointing to a single-story shotgun bunkhouse at the rear of the estate, a few hundred feet from the cemetery where I would soon shovel dirt onto the coffin of a deceased nun, filling in the hole a professional gravedigger had dug a day or two earlier. One of my odd jobs — no skill required. “You can stay weekends, too, if you like,” Sister Gladys said, showing me the men’s table in the little break room tucked between their large, noisy kitchen and the loading dock. The pay was 30 bucks a week for five eight-hour days, plus room and board.

Somewhere north of 50, Sister Gladys served as the order’s treasurer — the économe général, a Latinate encumbrance only Roman Catholicism could have dragged into the 20th century. As such, she supervised the finances of an order that ran two hospitals — one of them, St. Francis General in Lawrenceville, among the largest in the country — as well as dozens of parish schools, two nursing programs, several academies and other institutions. When she showed me around the convent’s 32-acre property, I knew little of that. She was just a welcome boss whose direct, decisive and friendly but formidable manner I immediately appreciated — a robust antidote to the moping narcissism of my infinite, imagined sinning. A high-functioning executive managing a complex operation, Sister Gladys left no doubt that she knew what she was doing.

That terrifying night is the only time I ever spoke to my father about his drinking, paranoia and menacing violence. He was drunk. I was shaking and numb with fear when I confronted him. I remember little of what I said as I locked his wrists and ankles in leather cuffs and belted him to the ambulance gurney.

She seemed to get my spiritual chaos as well. “You can attend our Mass if you like. Just sit in the back pew. Al does that sometimes,” she said, referring to the boiler-room guy, a much older, longtime resident who became my first friend after seminary. In the early days at Mount Alvernia I did attend Mass, entering the imposing main building through its cavernous boiler room, then threading through deserted, institutional corridors toward the convent chapel — all of it an uncomfortable rhyme with my Capuchin life. But in this chapel, instead of the bass and tenor rumble of male voices in unison, it was all soprano and alto, a hundred or more singing and chanting women in their late teens to late 80s, praying familiar words but in different, lighter tones. I liked the sound of their female voices lofting in harmony. So uncomplicated, it seemed — praising, beseeching, adorational. Why couldn’t I just do that?

Mount Alvernia also served as the order’s novitiate. The novices, more than a dozen, wore bridal white habits and filled the front rows of the chapel. Behind them, dozens more nuns, wrapped in black (a few in solid white, the cooks and nurses), a yawn of 15 or 20 vacant pews between them and me. Sometimes I goaded myself forward to receive the Eucharist, filing in self-consciously behind the last of the nuns, those retired sisters still able to make it to chapel. Mostly though, spiritual voyeur, virginal man in a room full of virginal women, I followed the Mass from my pew near the exit, longing for the purity I thought those novices embodied, a tangible force glowing through their white robes.

Occasionally I’d long for one of them, but only for the briefest of moments and far from understanding the full nature of my desire. In rare sightings of these young women as I went about my work, I’d cast a furtive glance, drawn by a peal of laughter, the hint of a shapely body, a flash of passing eyes — wondering who might live behind a particular set of wraps and veils. With no opportunity to find out, and too ignorant, inexperienced and afraid to want to, I’d clamp down with the old “custody of the eyes,” turning back to the mower I was cleaning, or the hedge I was clipping. But not before wondering whether they had noticed me, smothering that thought as well. How could I possibly be lusting after nuns?

II

When I started at Mount Alvernia, I wanted nothing more than to get my soul in order to return to religious life, perhaps as a Trappist. One classmate had left for Gethsemani where Thomas Merton was his novice master. Another left a few weeks later for their monastery at Berryville, Virginia. I’d heard something about monks sleeping in their own coffins. Was that the Carthusians? The Camaldolese? Maybe my soul needed a more severe spiritual tradition to get itself in line. I spent my first week’s pay at Kirner’s, the Catholic bookstore in Market Square, excited to buy my own copies of Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain, The Sign of Jonas and Seeds of Contemplation.

By the time I left “the Mount,” I had drunk my first Iron Cities (at Bucket of Blood on Lawrenceville’s Butler Street), swung golf clubs at a driving range and driven to Washington, D.C., over Labor Day weekend. I climbed the Washington Monument, stood in awe at the feet of Lincoln and marveled at the Iwo Jima memorial near Arlington National Cemetery, all under the influence of Bert, another temporary hire. A professional golfer who’d left the tour after his life had taken some terrible turn he never explained, Bert was my immediate supervisor. By night I read Merton in my bungalow bedroom, a noisy echo of my monastic cell. By day, spending time with Bert and the other men, I was becoming a civilian.

The men of the bungalow, together with the two full-time hires who lived with their families in Millvale, formed a kind of collective, institutional husband for the nuns. We did everyday work in support of their larger mission, pretty much unaware that we were also beneficiaries of that mission — men some top administrator had taken in, trusting that Sister Gladys would find appropriate work to tide them over a bad time. When Sister Gladys hired me, she emphasized mowing lawns as my main job. Summer work, even though it was early April. It’s clear now she was also “sheltering the homeless,” a work of mercy for men in serious need. Gospel work.

Two events, one an accident, the other an inevitability, drew me out a little further from the cloud and cloister of my nonstop, ever-concealed inner turmoil. Each happening forced me into a kind of agency in the world that had never been required of me before.

“Jim!” Sister Gladys shouted one July morning, charging across the parking lot, a sharp tone of alarm overriding her usual matter-of-fact instruction. “Get the stake truck. You’ve got to take Bert to the emergency room.” Bert trailed behind her, one hand cradling the other against his chest. It was wrapped in a white bath towel soaked through with blood that dripped at his elbows. Bert’s forearms and shirt were smeared with it. He had fallen backwards into a basement stairwell, pulling a power mower down after him. In those days before automatic-kill systems, he’d protected his head and face by jamming a hand into the whirling blade above him, shoving the mower aside, probably saving his life.

All the way to St. Francis hospital, Bert kept unwrapping and rewrapping that bloody towel, peeking at his mangled hand even as he directed my driving. He counted five fingers but saw that some were nearly severed. His golfing days were over and, until he recovered, so was his driving. Nuns were forbidden to drive in that pre-Vatican II time, and Bert had driven on weekends, filling in during the week when Andy, the regular driver, was unavailable.

Those duties soon fell to me. It felt like a promotion, and an upgrade in manliness. I’d gotten my license but never drove Dad’s car again. He’d checked the teach-your-son-to-drive duty box but could not afford additional insurance, much less risk my wrecking the car he needed to get to the mill. Besides, I had only been home from the seminary during summers and seminarians didn’t date, so why would I need a car? I understood it all. I walked to Mass or family errands, took long hikes and rode the trolley, but a late-teens guy not driving in the twilight of ’50s America felt wimpy. I’d never been a car buff, never had the urge to vroom-vroom Dad’s humble Ford or squeal its tires. Maybe that’s why I remember as embarrassing the pride I felt while bouncing along Mount Alvernia’s grassy slopes on the Triplex mower, or mastering the powerful Gravely self-propelled tractor. Other young men owned cars or drove their fathers’. Now at least I was riding a mower. Didn’t that make me a little manlier?

At least that?

After Bert’s appalling accident, I still mowed lawns but also drove nuns in cars: Sister Gladys to see her ailing brother at the VA Home in Highland Park, superintendents to parish schools around the city, top administrators to meetings about founding a women’s college in Milwaukee. They always rode two or more to a car. I kept respectfully quiet while overhearing these smart, accomplished women discuss hospital budgets, develop end-runs around interfering pastors and diocesan officials and strategize how to maximize space in a school addition with limited dollars. It was that eavesdropping that invisible underlings do, learning far more about the institutions they serve than its principals guess.

The sisters also taught me the map of Pittsburgh, untangling its notoriously confusing web of narrow, curving, cobblestone streets, hills and hollows, its uncountable bridges and the unmarked boundaries between separate communities. The flow of conversation served to mask what interested me most — the details of the mission I felt I was serving in my small way. Maybe I can make more of this job. Mount Alvernia must need lots of snow shoveling. Wonder if they have a plow I can drive? Trappist life wasn’t drawing any closer. By late summer I began to hope for early and deep snow.

III

The event I called inevitable required more skill than did chauffeuring nuns around Pittsburgh, but it came about almost as abruptly: I kidnapped my father into the 300-bed psychiatric wing of St. Francis General, the same hospital to which I had taken Bert a few months earlier. Sister Gladys had a hand in this involuntary hospitalization, counseling my mother in secret phone calls and getting me hired on at the hospital. Since she is long gone, I can never ask her how informed and deliberate her actions were. Yet it is through her that I know today that what we did in 1961 was illegal, but also profoundly wise and humane. It was one of the ways in which the sisters at St. Francis had been saving lives since the hospital’s Civil War-era founding — more than a century before they began distributing those wonderful, ubiquitous “Do You Feel Safe in Your Home?” brochures.

Several years after my father’s death in 1980, Sister Gladys arranged for me to copy his records from the two-week hospitalization that my mother, my brother John and I forced upon him on December 8, 1961, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. That terrifying night is the only time I ever spoke to my father about his drinking, paranoia and menacing violence — and then only in tender euphemisms. He was drunk. I was shaking and numb with fear when I confronted him. I remember little of what I said as I locked his wrists and ankles in leather cuffs and belted him to the ambulance gurney.

I searched out Sister Gladys so many years after the incident because I needed to fill in the soul-killing silence that my mother’s no-talk rule had imposed. Those 19 subsequent years, Dad had lived in sobriety, though not healed in spirit.

Several more decades would pass before I recognized the most telling information in Dad’s records. The admitting ER physician had sworn to a falsehood, saying he had “examined” my father “with care and diligence within one week prior to the date of this certificate; and . . . the said patient is mentally ill and in need of treatment and care in a hospital for mental illness.” This “certificate of physician” put St. Francis General in compliance with Pennsylvania law about “detention . . . for temporary care,” but those two crucial clauses were an utter fiction. “Oh, you did an intervention,” a therapist once said to me. No, it was a seat-of-the-pants, make-it-up-as-you-go ambush, the only way we could have gotten Dad the help we all needed. And St. Francis knew how to handle such dangerous circumstances.

The night we kidnapped him ended, for my 12-year-old sister Kathy, with a dramatic gesture. Seeing neighborhood gawkers on the street as the ambulance team slid Woody McKenzie into the vehicle (“They finally did something,” one said), Kathy pulled down the shade in her bedroom, turned on the light, and folded her hands near the window, imagining she’d made a silhouette those neighbors could discern as a call for prayer. She was begging for help in the most important form we knew.

The nuns of Mount Alvernia and their sisters on that matching hill across the Allegheny at St. Francis prayed, too, daily. But a century of service in the everyday work of medicine, education and meeting the needs of the poor had given them a grounding I lacked. So it was that when my brother John had called the bungalow that October before my father’s hospitalization, asking me to pick him up at the P&LE train station, Sister Gladys swung into action again.

John was also in flight, though I had been too immersed in my own turmoil to recognize it. While mowing lawns and driving nuns, I’d imagined my younger brother had received the vocation I had ruined, the Holy Ghost passing the torch on to him in some mysterious way. John had gone into the Capuchin brothers right after his graduation from high school. Years later I learned the details of my brother’s graduation-night horror: how Dad had strangled him with his own necktie, John still in his Pomp-and-Circumstance suit, trembling on the living room couch, not fighting back. “But I made it clear to Mom and Dad he’d have to kill me the next time,” he said. “They knew I meant it.”

That’s why he had told me, on the night I picked him up at the station, that he was not informing them about his leaving the Capuchins. He was just leaving. I knew Mount Alvernia did not need any more workers. The bungalow was full. What could I do?

“You and John meet me in the boiler room tomorrow morning,” Sister Gladys had said, handing me the keys to the stake truck. “We’ll figure something out.” Before the next day was over, John had a job in St. Francis’ new, nine-story rehabilitation wing and I would be working in the psychiatric building. Neither of us had any training whatsoever. One day John needed a place to stay, to feel safe, to regroup; the next we both were buying hospital whites in a uniform shop on Penn Avenue and following the leads Sister De Chantal had given us to find a sleeping room near the hospital.

If my time in the men’s bungalow at Mount Alvernia rescued me from a perilous place, my work at St. Francis would take me to another level. I remember the feel of the time card vibrating in my fingers as the clock klonked those little purple numbers that registered the beginning of my duties each day. How definite, clear, almost important. Clocking out eight hours later, I knew I’d spent a meaningful shift, applying compassionate muscle to bouncing limbs and torsos as Dr. Chavern administered shock, and forcibly restraining patients with the help of other psychiatric attendants as needed — using the same leather straps I’d smuggle home in a pillowcase on the night of my father’s hospitalization. I especially liked writing occasional notes in a patient’s chart when I saw or heard something I thought might help the doctors understand the mysteries of a particular illness a little better.

Before long I met a man who had jumped off a bridge into the Allegheny, producing the only full body bruise I have ever seen: arms, legs, belly and chest marbled with a rainbow of colors as his body healed. “Hey, I wasn’t diving for the Olympics,” he said. “I hit that water flat. I just wanted to die.” But his spirit healed, too, and like most patients he went home after a few weeks. Also like most patients, he’d had shock treatments. Those records Sister Gladys later helped me retrieve contain “Treatment Form No. 2 (For Relative of In-Patient),” authorizing “electric or metrazol treatment” to my father “as needed.” Mom signed at the bottom, followed by 18-year-old John as “Witness.” The admission record lists “Informants: Wife, Catherine. Son, James.”

Though I remember with great clarity how small and meek my father looked as he rolled silently by me at shin level on that low ambulance gurney, off into the psych building — this once-terrifying figure in our lives — I can never know any more about how we made it happen, what exactly Sister Gladys said and did, or how St. Francis finessed the legalities of involuntary commitment. After a century and a half of practicing what was often state-of-the-art medicine, St. Francis was finally devoured in 2002 by other medical systems, a victim in part of its own unchanging (though never so expressed) bottom-line mission statement: “Embrace, like Francis, the leper.” Stories such as this one were common: Sister Adele, whom today we would call the hospital’s CEO, would follow discharged patients out onto Penn Avenue to ask if they had a place to sleep that night. When the answer was “no,” she readmitted them until they did. The doctors would have to treat them a while longer, until someone worked it out. She was a Franciscan through and through.

What happened to St. Francis of Assisi at La Verna may have been in some way otherworldly. For me, the effect of Pittsburgh’s Mount Alvernia, especially Sister Gladys, was this-wordly. It brought me into the world as I had never known it. It wounded me with blessed reality.

James McKenzie, a University of North Dakota professor emeritus of English, now lives and writes in St. Paul, Minnesota.