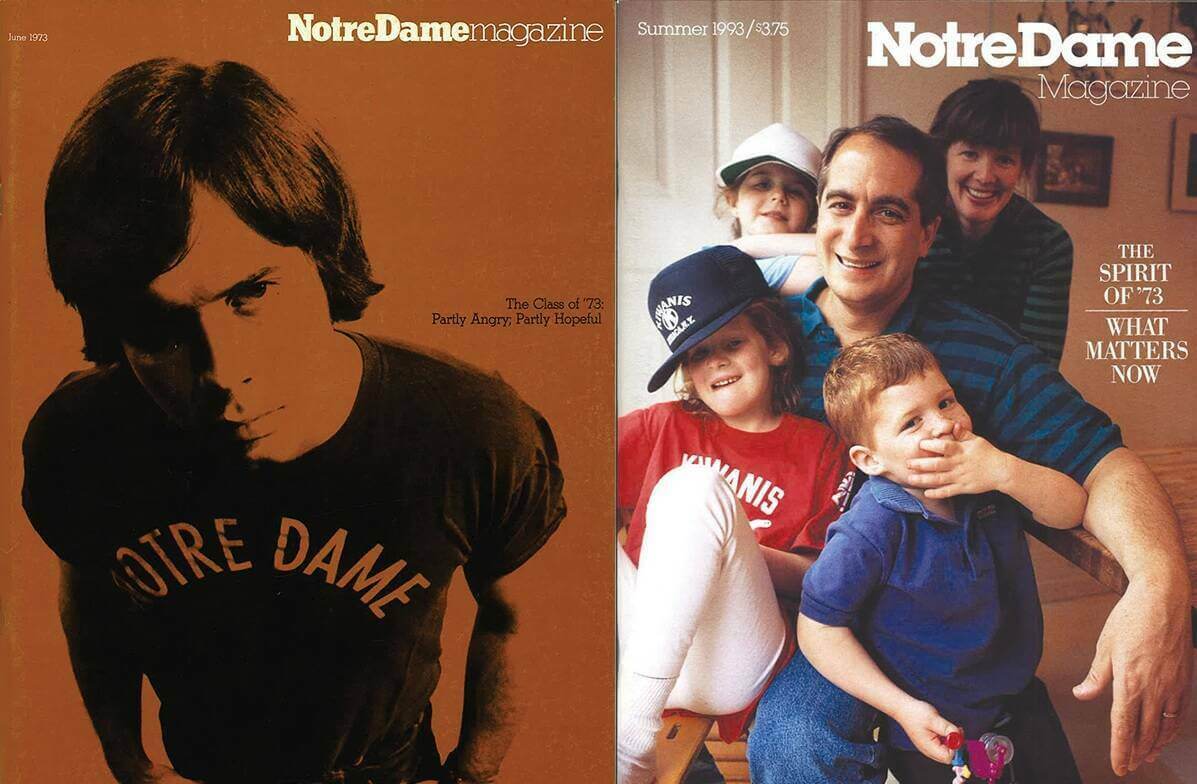

It’s the Ship of Fools theme in reverse: Instead of assembling a disparate group of people into a confined space for observation, you disperse a group of people from a confined space — say the Notre Dame campus — and let them wander for 20 years. Then you take a look to see where they’ve ended up.

That was my assignment and, as the little boy in the joke says, “I worked the problem out seven times, and here are my seven answers.”

By the time I completed the last of my interviews I was wondering what to make of all my audiotapes and scribbled notes. I couldn’t figure out what the unifying principle was, what common thread runs through these seven lives today.

Their postgraduate lives are as patternless as the list of places where they’ve chosen to live: New Mexico, Washington, Tennessee, Illinois, New York, Maryland, and France. In my talks with them, every time I began to sense a connection it disconnected with the next interview. Every common trait I found in four or five was completely absent — and sometimes contradicted — in the others.

Even the common thread of membership in the Class of ’73 is poblematic: I asked John Walsh why his essay in Notre Dame Magazine mentioned events that happened a year before the Class of ‘73 arrived on campus. Turns out he was in the five-year arts and sciences/engineering program and was already a sophomore when the rest entered school.

Seven Domers, then, roughly the same age. Professor Ed Cronin used to tell us that you can no more be an ex-Catholic than you can be ex-Jewish or ex-Irish, that it is an identity. By the same token, having done your time, is it possible to be an ex-Domer? Perhaps that depends on what that indelible character is.

It cannot be That Which We All Think Of. Oh, there are such people: I once met a woman who had been married to a Domer. Her first clue, she told me, came in the mid-’60s when they went to South America for two years with the Peace Corps and he bought a $3,00 short-wave radio. She thought it was so they could listen to the BBC World Service news. Within the alumni family, we do not even have to finish the anecdote, do we?

I encountered none of that, though Paul Dziedzic and Greg Stidham each laughed about the raggings they take at work when Notre Dame has a bad outing on the gridiron or hardwood. While both are very interested in sports, neither can be classified as a Rah-Rah.

In fact, the enthusiasm for the school that I encountered had nothing to do with sports, and the most ardent loyalist was also the most phlegmatic of the seven personalities. Janet Cullen Abowd ’74 laughs off husband John’s low-key manner. “His brother Greg (’86) is the one who gets all misty-eyed” over Notre Dame, she says. “He turned down Harvard and MIT to go there.”

John Abowd agrees, declaring, “I came to get my college degree and then get on with life.” But then he proudly notes that he and Greg are two of a total of nine Abowd siblings who streamed through the University. After virtually glowing over that distinction, Abowd then whiplashes back the other way, disclaiming any virtue in such a record. “I learned how to be a parent by being the oldest of 12 siblings: I routinely gave out advice that was routinely ignored,” he chuckles. “I never told any of them to go to Notre Dame.”

Perhaps that is the common thread: Abowd gets a kick out of three quarters of his family having trekked through the school but is insistent about how little that matters, really, and how foolish it would have been for eight of his brothers and sisters to file like ducklings through the wrong school simply because it had been good for their eldest brother.

Of the seven who wrote those essays in this magazine two decades ago, not one refused to be interviewed or expressed regret at having attended Notre Dame. All the same, not one has simply conferred his loyalty without due consideration. The affection they have for the school has been thought out.

This is no recent development: In his magazine essay of 20 years ago, then-Observer Editor Abowd revealed the grudging affection at the center of his and his classmates’ complaints about the place. “The student who doesn’t think Notre Dame is worth improving won’t waste his time making suggestions,” he wrote, adding that “the suggestions of those students who have taken the trouble to research their positions are surely the best market information this University will be able to find.”

Today, several of the seven qualify their affection toward the school with remarks like, “but I don’t do the club stuff.” They are irreversibly Domers, but they don’t wear their affection on their sleeves.

Jim Fanto told me his memories of college, graduate school and law school are not so much of the places — Notre Dame, Michigan and Penn — as of the people he met in each place. Still, Fanto gives the place credit in one department. “When I think back on Notre Dame, I think of it as one of those places that is different,” he says. “There must be something about it, that they get all these good people who go there, so I think back fondly on it as an institution that attracted those sorts of people.”

Walsh is much more enthusiastic in his endorsement of the University, but again it is an earned endorsement. “I went to graduate school at Harvard, at the Kennedy School there, and I was really struck at that time that Harvard had money and advantages and wonderful scholars and all sorts of things that make a university a wonderful place, to an extent that Notre Dame could never dream of,” he recalls. “But I didn’t think it had the spirit — and I don’t mean pep-rally spirit. I mean the spirit of collegiality, a camaraderie that I found at Notre Dame.”

In this group, nothing is automatic, everything is carefully considered, and there is always another shoe to be dropped. Walsh and Abowd each think Notre Dame should spend less energy than it does now agonizing over its Catholic identity, though they come to the argument from different directions: Abowd would prefer to see more emphasis on academic excellence in a pure sense, and he denies that a search for excellence shortages undergraduates or endangers Catholic identity.

Walsh, in contrast, finds it hard to discuss issues of “Catholic identity” in the face of physical growth he fears will dilute the intimacy of Notre Dame — whatever names you put on that sense of community. “The thing that’s bothering me does not necessarily involve the loss of a focus on Catholic values, though it could; it’s of a piece with that whole trend,” Walsh says. “But it seems to me there is an excessive fascination with buildings and centers and new quads and that kind of thing.”

But the common thread is not their strong, if questioning, loyalty to du Lac; it is how much they have thought about that loyalty, and about everything else in their lives, how carefully they have considered the choices they’ve made. Whatever question you ask is answered as if the matter has already been thoroughly mulled over.

For the past 20 years these seven alumni, these seven Domers, have been asking questions of the world, and of themselves. For one thing, they ponder family responsibilities and their own places in their families.

“How do people who don’t have kids put their lives in perspective?” asks Paul Dziedzic, describing a type of continuing therapy he goes through: namely, remembering and re-evaluating his own childhood by watching his children experience growing up. That therapy goes on every day, not just on weekends.

Dziedzic was a rising star in the world of Washington state politics when he decided to slam on the breaks. He realized that he was missing something important, particularly in the months when the legislature was in session. He decided that had to change.

Fortunately, he got a great deal of support from his contemporaries in government as well as from Kathy, who had stayed home with their three children until their youngest was in school full-time. “I realized that I would not be able to do my job well and be a father, that I would not be able to do that ‘job’ well, too,” he says. “I worked through the thought process, and it boiled down to, ‘What is most important to me?’ There were people I met with, one of whom is now my boss, and several of us spent a couple of long mornings together asking ourselves what was really important and listing those things.”

He realized that the children would not wait for him. “The age they are at now won’t ever come again,” he says. “The Little League stuff and the time coming back after soccer practice when a tough thing has happened — being there then is when you are a parent. This is the most important thing we will ever do. It is the center of what we are and the other stuff fits around it.”

For Dziedzic, that means combining a half-time job with a three-quarter-time job in ways that leave him free for his family. There was financial sacrifice in his choice, but the basic bills are paid and anyway, he notes, children’s expenses tend to expand to fit income, so they wouldn’t feel like they had any more money no matter how many hours he and Kathy had worked.

Floyd Kezele has turned the juggling act of job and family into a three-ring circus, but a highly entertaining one. He has three jobs: college instructor, consultant to several Native American communities seeking to establish their own justice systems, and professional homebuilder. Meanwhile he and his wife, Emily, a school teacher, are expecting a fourth child. It all keeps him fairly busy.

“Yesterday I was racing around doing some things, checking on one of the homes we were building,” Kezele reports, describing what he calls a typical day. “My watch went off wrong and I raced home before going to pick up my kids. In the meantime, the solicitor and chief justice of the Navajo Tribal Court drove up, and they were talking to me about a conference we were going to have on matters of interest to tribal courts in the area. Then the chief justice asked me something about the house and we got off on a tangent because he’s building a house. It finally got to the point where I had to say, ‘Look, I hate to do this, but I’m going to have to run, because I have six Cub Scouts waiting for me at the school.’”

The togetherness with their children that Kezele and Dziedzic have actively sought came to Greg Stidham in a different manner when his first marriage broke up a decade or so ago. It did not fall into his lap. The matter involved a great deal of effort and self-education.

The children were young, the divorce unpleasant, and Stidham found himself in a custody fight in Tennessee, where daddies don’t get custody. “That was the first time I learned there were men’s rights groups, or fathers’ rights groups, around the country,” he recalls. “There had been one in Memphis, but to my dismay I learned that that group had been disbanded about three years earlier.”

He resolved that problem, in a manner I’ve come to think of as typical of his group of Domers. “I came in contact with two or three people who had been involved before and we started a new organization, of which I was the president and continue to be the titular president. We went out and solicited members and made the community aware of our existence, and we did some politicking to get laws changed in the state.”

There was a happy ending for Stidham when he gained the access and legal standing he needed to continue as a strong parental figure to his two boys; a still happier ending when he and his “ex” arrived at a civil post-divorce relationship that allows them to work together as parents, and a happiest ending when he married Abigail, with whom he has rebuilt his life as husband, father and, oh yes, head of a pediatric intensive care unit–also a somewhat demanding role.

But there is a difference between finding your own way through that thicket, Stidham says, and resolving the inherent issues: “I think the way our society handles domestic matters — particularly divorce and its impact on children — is still a travesty. We’re in the Dark Ages in terms of what’s best for the kids.”

Personal decisions also intersect with universal issues when these members of the Class of ’73 discuss the Catholic Church. Here too, loyalty is not given without serious reflection. The seven vary dramatically in their attitudes towards the church, though they are alike in having well considered explanations for where they stand.

No one is more steadfast or passionate than Linas Sidrys who, when he refers to himself as an orthodox Catholic, is speaking not of the Eastern or Russian Orthodox churches but of a very conservative Roman Catholic Church.

“There is only one Catholic Church, and I’m in it,” he says. “There are some people who are alienated from that, and it’s a tragedy that they’re not accepting some of the basic tenets of the Catholic Church. But they’re going to be the ones that are going to fall off eventually, unfortunately for them. You can’t pick and choose what you’re going to accept.”

For Sidrys, believing in the church is more than a question of transubstantiation versus consubstantiation, and far more important than where you spend an hour on Sunday morning. He grew up Lithuanian, met his Lithuanian-American wife at a folk dance, and they are raising their eight children in a home where Lithuanian is the primary language spoken. In addition to his regular ophthalmic practice, he maintains a practice in a Lithuanian section of Chicago's inner city and he returns to Lithuania regularly to donate his services there.

It is to the church that he gives the credit for Lithuania’s survival through the decades of communist oppression. In his mind, to turn away from Roman Catholicism would be to turn away from Lithuania. To moderate the essential elements that make up the church would be to compromise that which made Lithuania strong enough to withstand its years of occupation.

Before the demise of the Soviet empire, “I had already been to Lithuania and seen a culture that had no faith, a non-Western culture,” he says. “All of the Soviet culture imposed on Lithuania was a very brutal Eastern Asian, almost Mongol, culture of brute force and intimidation.”

At the other end of the ecclesiastical continuum is Paul Dziedzic, who has rejected the church, not specifically for its teachings on birth control and abortion but for the broader attitude implicit in those positions and in its position on eligibility to serve in the clergy. His current standing places him a long way from the young man who, at Notre Dame, was briefly involved with Opus Dei and considered lay ministry.

Paul and Kathy Dziedzic were married in the church and their daughter, Erin, now 15, was baptized Catholic. But by the time their sons Andrew and Bryan came along a few years later, they were no longer practicing Catholics. At first it was the drifting-away of a young, mobile family, he says. “But, when you move several times, connecting with a parish is a choice. You don’t have to walk in to see your parish priest and say, ‘I’m not coming back.’ When you move, you have to bother to find someplace new — we’ve moved three or four times, and along the way it was just not important to reconnect.”

When the question of going back arose, the debate was over whether there was a just and meaningful place in the Roman Catholic Church for Kathy or Erin. As a man, Dziedzic admits, he could have been happy enough in a progressive parish where those troublesome issues were not rigorously considered, but as a husband and father he could not. That was when the somewhat nebulous lack of a decision to reconnect with a church became, for the Dziedzics, a solid decision not to return. They did, however, resume formal worship and fellowship and are moderately active in a local Presbyterian parish.

For the rest of the seven, attitudes toward religion fall somewhere between Dziedzic’s definitive rejection of the church and Sidry’s militant acceptance of the One True Faith. Stidham and Fanto are the least passionate on the topic. For them, the perceived shortcomings of the church seem like the peccadillos of a black-sheep uncle, something to be noted but not dwelt upon. Stidham, though alienated and somewhat embittered by his experience with the church throughout his divorce and subsequent annulment, attends church for the sake of his sons. (He interrupts that admissions with, “I hope my mother doesn’t read this!”)

Fanto, who recently became a first-time father, was married in the church and had his daughter baptized, but he exhibits a casual attitude toward the church. “I’m of recent Italian background, and someone was telling me that’s how Italians are: They’re just Catholics by birth, and then they don’t have to pay attention to it. They feel it’s just part of their heritage, but they don’t have to care or make an effort.”

If Corbin’s Law of Immutable Catholicity can be twisted to apply to Notre Dame and its graduates, Fanto is a living example of the rule in its pure form: Though he barely practiced his religion, he says it would be an impossibility for him to leave the church. “If you’re brought up as I was, it becomes something cultural and part of you. You might say you don’t really believe, and that might be true — or that you don’t like this or that — but you’re always reacting to it in some way.”

There is the matter of balance, the question of what the church should demand and what it should offer. Walsh counterbalances true conservative flavor of the international business community in which he works by attending an urban parish with a multicultural, socially progressive agenda, including an active gay community and a female pastoral director. “It has a different flavor, a kind of urban, polyglot character in a little church, and it also has a tradition of very good preaching,” he says. “We were looking for something a little more intellectually stimulating, which it definitely is.”

Kezele, in contrast, has undergone a change of attitude toward church-hopping. He was once active in a new parish outside of his neighborhood: He served on its council, helped build a parish hall and worked to help the parish appeal to the three cultures in New Mexico — Anglo-European, Hispanic and Native American. Then he returned to his neighborhood parish. “I had to be consistent to a principle I had discerned, that it is best to stay within the parish to which you belong,” he says.

“I think that if we’re Catholics within the church, we should be Catholics first and Americans second, not Americans first and Catholics second,” he continues. “When I was president of the parish council at the church I church-hopped to, we had a very good developing faith community there. Our council made unanimous decisions that our pastor went along with, though he had the canon-law authority to veto them. But then something came up where we talked about it and had a vote on it, and it came out to something like a five-to-three decision. Afterwards, I praised people for finally speaking their minds and not being afraid to express disagreement. But we ended up having several votes like that over the next several months and got into some problems.”

Governance by consensus worked, he explains, as long as the decisions of the council did not run counter to canon law. But democracy did not work. Kezele nonetheless denies the view that the ecclesiastical hierarchy represents a sacerdotal dictatorship. “A lot of outsiders think that the pope, speaking from the chair, is one man up there who has made up his mind and that’s it,” he says. “That’s not the way the church operates. The issues, when they are put out, are well-studied. These writings of the pope are well-studied. They are given forth as teaching instruments, and only once since the doctrine was defined have they been given forth from the chair. Many Americans don’t understand that, and even Catholic Americans say, ‘Well, the pope talks about birth control. but he doesn’t play the game, so why should we listen to him?’”

As it is for many American Catholics, however, that’s precisely the point where John Abowd dissents. It reflects, he suggests, the problem faced by a church with its social roots in less developed countries and an unwillingness to distinguish between transitory and eternal issues. “All of what the church teaches and preaches about family life is either reasonably applied — what you can do for your children, what you should do for your parents, what you should do for the people around you — or silly,” Abowd says. “I find the church’s positions on birth control, divorce, abortion, family life, the whole litany of things people usually talk about when they talk about the church, very difficult to defend.”

It is not a matter of personal crisis, Abowd insists. He will continue to attend his neighborhood parish — he does not believe in church-hopping — and he insists that his involvement in the church is not simply a matter of providing a firm base for his three children. But he raises a pragmatic concern about what will be left in the church for American children to inherit if the church continues to demand celibacy from its clergy.

“I have nothing but admiration for the people who have chosen religious life and to live by those rules,” he argues. “But certainly, you can’t make a reasonable case for those rules being a critical part of religious experience. They don’t have any shortage of those sorts of religious people in the parts of the world the pope worries about, so he doesn’t have to worry about it. But we do.”

That future increasingly is out of the hands of the Class of 73, as they seize the reins of the present and prepare to leave the future to their children’s generation. As their fifth decade unfolds, it is time to begin thinking about pensions and retirement and to start figuring out how to balance the books before the audit is taken of what they did with their stewardships.

That’s not a comfortable line of thought for Jim Fanto, whose life recently went through the twin changes of first-time fatherhood and passing 40 — just as he was in the process of contemplating yet another move in what has been less a career than an oddly successful search for the next adventure.

At first glance, Fanto’s resume is a series of touch-and-go landings, but his lack of longevity in any particular career reflects no dearth of talent: He clerked for Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun, hardly a dilettante’s position, then went back to school to finish a doctorate in English before going to work in international business law, the track that took him to Paris.

“Maybe I’ve done too much in the way of wandering around,” he concedes. “I’ve usually tried to do things that were interesting to me. It was interesting to get a Ph.D. in comparative literature, it was interesting to go to law school, it was interesting to be a law clerk, and it’s been interesting to be in Paris, practicing. But you begin to realize your own mortality. I’m now 41 and I want to do something interesting yet again, but I don’t know what that is. Should I just accept what is safe and not as interesting? I find myself saying, again, ‘I don't care. I just can’t stand it if it’s not interesting.’”

With a new child and a wife whose own legal career is established, Fanto has been talking to a law school in the States about teaching. But he plans to ponder his next move very carefully. “I wouldn’t even have given it a second thought a decade ago. But when you realize you’re a little older, you stop and say, ‘Gee, should I be doing this?’ A lot of people are very settled down at 40, and they start getting bored, and whether they have said it or not, the challenges are gone. You need something new.”

For Linas Sidrys, the future would seem to hold no fresh challenges but rather the same battle between good and evil that raged for years before he stood nearly alone on Notre Dame’s campus during the Vietnam War as the voice of militant anti-communism. Today he seems to see the world as a dark, foreboding place where the spores of anarchy sown in those years are bursting forth in chaos and destruction.

In his magazine essay 20 years ago, Sidrys called for medical students to spend some time on more cosmic issues than their next set of grades, but he says there has been no change in what he saw then as self-preoccupation on the part of Americans. He denounces contemporary society like a modern Jeremiah.

“The underlying philosophy of America is that you’re here for the pursuit of happiness, and self-sacrifice for the common good has been forgotten,” he says. “We’ve forgotten the American tradition of helping our neighbor. That definitely was the American culture, more than any culture in Europe, because this was a pioneer country. Would I leave this country? If these trends continue, it may not be a place where anyone would want to live.”

The other physician among the seven, however, has a more positive view of the world, even though time weighs more heavily on Greg Stidham than on most of his contemporaries. In his case, it is neither a matter of counting his lost and graying hairs nor of worrying about the geopolitics of the coming century. Two years ago Stidham was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, and while he feels few ill effects and no disability from the disease thus far, he finds it does tend to focus the mind.

“It’s not limiting physically, nor is it a preoccupation,” he says. “It’s more like dark clouds on the horizon. It may be coming in, but you don’t know how fast, how bad it’s going to be, or even if it’s going to come at all.”

He’s lost any tendency to procrastinate he might once have had. The bad news came just after a hiking trip to the Rockies, and the family returned to hike again the very next summer because the unpredictable attack-and-retreat nature of MS makes long-range plans risky.

But it would be wrong to view Stidham as some self-indulgent Yuppie, worried only that he might not get to trek up through Rocky Mountain National Park next summer. Far bigger questions loom, questions of things left undone from an age long ago when the members of the Class of ’73 were young and had all of time stretching before them.

“There are things I’d like to be doing, priorities I have,” Stidham says. He is looking into going to places where children need health care and are not getting it, either overseas or in forgotten corners of America. When he found no handy repository of information on that subject, he began creating a database to assist other physicians in locating places where their talents are needed.

“I think there were a lot of us in the late ’60s and ’70s who had this vision of wanting to change this world and make it a better place,” he says. “Some of those people really wanted to change the world on a global scale, and others found their talents such that the worlds they could change were the private worlds of individuals. I certainly am more of the latter type.”

Looking back, it’s clear the seeds of that desire to change and the origins of that ever-questioning nature were planted in the era in which they found themselves at Notre Dame. “I wouldn’t trade the experience of those four years for any other period in which to grow up,” Stidham says. “I think the war was the single most important issue that forced us to think seriously about ourselves as human beings, about our relationships with other people and with the world as a whole, about our responsibilities to the world as a whole. It was that issue that forced us, within the isolated bubble of Notre Dame, to think about those things that I was going to be thinking about for the rest of my life.”

And Fanto recalls, “It seems I spent my whole time for four years arguing with people. We still had a lot of fun, but everybody was highly politicized, one way or the other. You just felt you had to take some sort of position.”

To understand how these very different alumni fit together, it helps to consider what they wrote those 20 years ago. Greg Stidham entered a plea for compassion. Paul Dziedzic thanked those along the way who helped him clarify the things that mattered to him. Linas Sidrys called upon medical students to examine their values and not just their textbooks. John Abowd called for an openness to criticism. Jim Fanto denounced high-sounding generalizations and praised the unique gifts of individuals. And John Walsh conceded that much of the ’60s mystique was ephemeral but that Notre Dame represented “order among chaos.”

“And this striving must be paying off,” Walsh wrote back then, “because this place is producing a lot of good people, and a few great people, all of them better for having been here.”

At the time of this writing, Pete Peterson was the readership services manager for the Press-Republican in Plattsburgh, New York.