Each time I search the parlor closet for whatever is lost in my home, I encounter the dead between the cleaning supplies and holiday decorations. Most of the men whose images are in the box of ancestral photographs are characters in family lore, especially those who for generations were named James, William and Samuel, but most of the women and several men are now bereft of stories, their names no more adorned than are the facts on the gravestones of stillborns. The stories that I do know fly to the photos like swallows to Capistrano. Even the tragedies cheer me.

My father told me the story about my ancestors named James, which is my middle name. My paternal grandfather had an Uncle James in the north of Ireland whose skull was permanently dented by a brother who swung a hammer to end a teenage disagreement. Although literate before — a rare skill in his family — James found after waking from the coma that written English might as well have been in cuneiform. A few years later, he became a traveling bare-knuckle boxer, the matches held outdoors or in boxing pubs where straw was spread on the floor to absorb the beer and vomit of spectators, each fight lasting until a boxer was insensate or disabled. He wasn’t the only accursed James in the family. My grandfather had a brother James who was an ironworker and fell to his death from the skeleton of a building in Buffalo, New York, or in the parlance of the profession, “took the dive.” My father, another James, was in his early 40s and had terminal cancer when he told me what his father had warned. “Bad luck in the family, that name.”

My father asked his father, “So why in hell did you name me James?”

“We can’t give up hope — can we?”

After my father finished telling this story, I expressed my opinion that only someone already addled would become a bare-knuckle boxer. “Maybe,” he said. “But James didn’t give up.”

While singing stories bequeathed by generations of ancestors, some aboriginal people in Australia still make journeys over traditional routes called songlines, seeking to recreate the landscape and its creatures in what they consider to be a sacred Dream World. The tradition of songlines strikes me as somewhat similar to what we Americans do when we raise the dead by telling stories about our forebears.

Yet our recreated ancestors might then annoy us by telling an unwelcome story about us; I know because I was told it in the middle of a night. I must have had thousands of dreams over the decades, but the dream with the story is the only one I can recall vividly — other than one about a bear that I saw in the flesh behind my house the next day. I had fallen asleep with my bedroom window open to the calling of frogs in the pond beyond the yard, and in the dream with the story I heard booming knocks. Or was it a bullfrog hosanna? I opened the front door of the house and saw on the lawn my ancestors leaking from darkness and into the beige cast and grey penumbra of the outside lamp. I was happy about the visit until several drifted inside, sat at the kitchen table and informed me by nodding in unison toward an unoccupied chair that they had come for more than a meal.

I awoke alive.

Once on a March predawn, when the weather was inhaling winter and exhaling spring, I found myself between sleep and wakefulness, dreaming and not dreaming. I heard the climbing and falling of surf, but could see no water or anything else and had a vague but alarming sensation that the earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep. That the world was without stories. Yet when I awoke fully, I saw a faint radiance of dawn on the formed and snowy yard beyond the low window that abuts my bed and realized I had confused my deep rhythmic breathing with the sounds of surf; that the world was full of stories, some yet to be told.

My wife and I have two children. Our daughter is named Hope Ann and our son Gabriel James.

Some days, I wake feeling I absolutely must travel a landscape of storied names. Perhaps the compulsion stems from a dream I had the night before but have forgotten by morning.

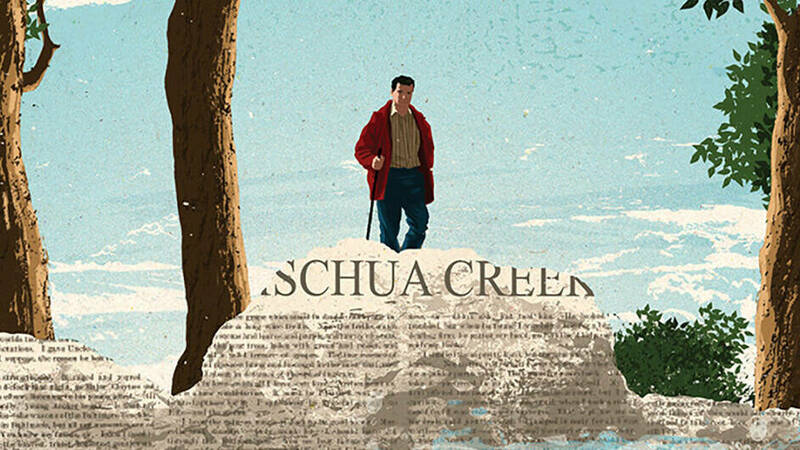

I drink coffee and pace my kitchen and parlor before pulling on hiking boots and setting out, my walking stick swinging like a metronome, my pace becoming rhythmic as I cross parcels of land known by the names of families who lived on them for generations. Soon I am a storyteller. Or maybe it is more accurate to say I am a voyeur and plagiarizer of ghosts, although to any deer hunter or ramp digger or mushroom gatherer who stands back and observes me, I must seem insane, mumbling with small, trial alterations the stories I’ve told scores of times before. I see the barn on what is known as the Seward property, though it is no longer owned by anyone with that name, and recall and tell a story about the mother of Lou Seward, who hangs herself from a hayloft. Next is a story about one of Lou’s brothers, who is shot in the leg by another hunter and bleeds to death.

Because I insist on a happier story, I cross a field and see that Lou is harvesting corn even though the field is now fallow and Lou long dead. I also see a neighbor, the son of a preacher, sprint shirtless from his own yard and across the dirt road and into the field, a halfback juking corn stalks and high-stepping over remnant furrows, breaking free into an opening of stubble, arms raised and waving side to side, shouting and failing to be heard over the barking of the John Deere, lowering his head into the haze of diesel exhaust, passing the towed chopper and wagon and catching up to the tractor. Lou brakes, shifts into neutral, disengages the power take-off. The boy bends at the waist, hands on knees, and catches his breath before standing straight and speaking. He has planted marijuana between two of the corn rows and would like to pick it. Awaiting a reply, he seesaws his weight from foot to foot and gazes up at the farmer on the green tractor as if Lou is St. Peter at the gates of heaven.

Lou thinks for a while. Finally he shuts down the machinery and removes a pocket watch from his denim coveralls. “You have a half-hour and not a tick more.”

Hours later, back in the house, he says to his wife, “Never saw that boy move so fast.” After swallowing another forkful of lunch, he adds, “You know, if I wanted to pay him with dope, he just might make a good farmhand.”

Or that is what Lou says in a story I once heard and have since embellished.

Despite what we recall and recreate, Americans are losing the stories of our place names, even those enlivened into tall tales. Seventy miles north of my home, historians in Buffalo have been unable to determine how the city got its name. And here in the hills where many of the old barns and houses are collapsing and the descendants of farmers have moved away to take employment in other careers, the land is home to fewer memories, is less haunted and more lonely. Ask someone the meaning of a place name and you might get the sort of response you would if you asked for the meaning of life. “Whaddya mean what is the meaning?”

I remember asking an older neighbor the story behind the name of a certain place. “I think my mother told me,” he said. “Back when I was a boy. But I don’t recall it now.”

I mentioned someone else who might know.

“He’s dead.”

We no longer know the meaning of the name Ischua. We presume it is an English mangling of a Native American name or phrase, which according to some people means ‘wild water’ and to others ‘floating nettles.’ I favor ‘wild water.’

Some of the early gravestones are weathered blank in the cemeteries of my town, the names surviving in oral stories, if at all. We know that Farwell Gulch is named for the town’s first permanent white settler, and that he built a dam and sawmill on Ischua Creek, and that the settlers who followed him felled many thousands of white pines, some of the trees centuries old, and sold him the logs, including the Hatch who settled on what is now named Hatch Hill Road and cut on his acres a million board-feet of pine. But I have learned nothing about the pioneer who gave his name to Munger Hollow Road or the person who died in Suicide Hollow or whoever famished on Starvation Hill.

So many local men died in the Civil War that I can guess why our town has roads named Union Hill and Union Valley and Yankee Hill, and yet here in the Town of Ischua in the Ischua Valley, which is drained by Ischua Creek, we no longer know the meaning of the name Ischua. We presume it is an English mangling of a Native American name or phrase, which according to some people means “wild water” and to others “floating nettles.” I favor “wild water,” because the pronunciation sounds as if spoken by fast water, like a mysterious direction given in an otherworldly dialect.

Ish-oo-way.

Even if the ghosts of places and ancestors never visit you, probably you are haunted on occasion. Probably you encounter your own ghost. Not a doppelgänger — an identical double — but an eponymous wraith from the past or future, a you who is not you, an old or approaching story. A while back, I visited the university where I had attended graduate school, and after touring the shapechanged campus and catching up with two professors and an administrative assistant I hadn’t seen in decades, I walked to the housing complex where my wife and I had lived and knocked on the door of our old apartment. I asked the guy who came to the door whether Mark Phillips lived there.

“No — sorry, nobody by that name here.”

Since I don’t much like him anymore, I’m not sure why I wanted to see the young Mark Phillips. He perhaps wanted to see me.

I have been thinking a lot about that visit to the University of North Dakota because recently I was walking up my long driveway at dusk to fetch the mail when a deer stepped from the weeds near the mailbox and stood looking my way. I can’t explain why, but I believed the deer was my wife, although not my wife whose brain has been seriously damaged by cancer and subsequent radiation treatments. I could see the deer’s form at the end of the driveway several hundred feet from me, and yet — irrationally, I admit — I was certain that my younger, healthy wife inhabited it. I stood still. The form began moving in my direction with such fluidity that it seemed to be floating over the face of the earth, gradually growing larger, and when it was so close that I could see its breathing, and it mine, I spoke.

“Margaret.”

The form leapt from the driveway and disappeared into a brushy gully.

In a wilder place than where Margaret and I have our home, a five-hour-drive distant, on an Adirondack landscape of wild water and mountains and forest where we might never be found should we lose our way, we own a small vacation cabin. Because Margaret can no longer bushwhack, I mostly explore alone. One of my journeys follows fast water that is rubbled with large boulders for its entire length. I have found no name for the brook on maps I’ve consulted in the cabin. It flows through the forested basin of a deep ravine and for a stretch is faced by cliffs that in one place touch the brook on both sides and force me to jump from boulder to boulder upstream over water that drowns out my mumbling of stories and the singing of birds. At the bases of the cliffs are small rock slides, and within one slide is a shallow cave, and on a vandalized wall of the cave is a replica of the earliest known personal name and story — in the form of an outlined human hand — gray because the stone is gray and surrounded by white paint that some explorer before me sprayed there with ancient hope and within sound and sight of a nameless brook.

Mark Phillips lives in southwestern New York. He is the author of a memoir, My Father’s Cabin, and a collection of essays, Love and Hate in the Heartland.