Barbara Johnston

Barbara Johnston

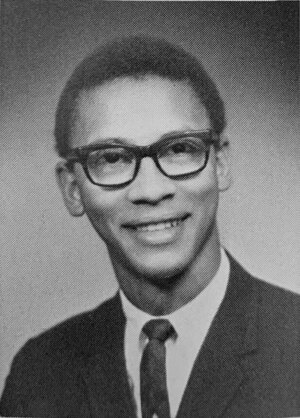

Francis X. Taylor ’70, ’74M.A., sat in Cavanaugh Hall that day and wondered if his dreams were dying.

From age 8 onward, Taylor had known his path. His heroes weren’t athletes, actors or artists, but soldiers. He idolized the honor and bravery he saw in movies and knew he would attend a college that could help him become a military officer.

But Notre Dame was making it too hard. “I was teetering on a 1.8 [GPA] that first semester,” he recalls now, 58 years later.

It wasn’t just the coursework. Having grown up in poverty in Washington, D.C., Taylor wasn’t sure whether he belonged on a campus of some 5,000 white men — and just two dozen men who were Black, like himself.

Knowing the story now, it’s hard to believe he ever blinked. Taylor’s military career was remarkable by any measure. He soared through the ranks of the United States Air Force, becoming a leading counterintelligence expert and holding a series of command positions.

In 1996, he achieved the rank of brigadier general and was named commander of the Air Force’s Office of Special Investigations. After retiring from the military in 2001, he served the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations in key national security posts.

If anyone had a straight line to the stars, it would seem to be him. The only wobble came during his college years at Notre Dame.

Taylor was different then, as a freshman in 1966, and so was the University.

In those days, regardless of race, students didn’t have much of a safety net. If there were tutors or counselors for folks who fell behind, it wasn’t widely known. Taylor had close friends, but they weren’t going to be able to save him from washing out.

His main worry was that he was wasting money his mother didn’t really have. He needed a plan, somehow, to get through the full four years.

“I knew I didn’t want to disappoint my mother,” he says. “I decided that no one was going to tell me I can’t make it here.”

Black enrollment inched higher in the 1960s. Notre Dame wanted Black students but didn’t exactly greet them with hugs.

“I didn’t feel any open hostility,” he recalls, chuckling. “There was some amazement that we were there. I wouldn’t consider those early years as welcoming years.”

Black Domers: African-American Students at Notre Dame in Their Own Words, a 2014 book compiled by Don Wycliff ’69 and David Krashna ’71, includes accounts of overt racism and subtler antagonism encountered by Black students.

“My freshman class had 12 Black students,” Taylor says. “That brought the total on campus to 22.”

Taylor had thrived at Dunbar High School, a renowned, historically Black institution in Washington. He had succeeded there in part because the school had a strong ROTC program, which fueled his interests. When he discusses how he found his way through Notre Dame, ROTC is one of the key building blocks.

First, he bonded immediately with two other Black freshmen in Cavanaugh, Arthur McFarland ’70 and Leon Jackson. They played cards and socialized together every night, chasing away isolation.

Second, he linked up with a South Bend family that opened its doors to him whenever he needed a break from campus. With so few Black women at Saint Mary’s College, the South Bend community provided much of the social life for Black men in that era. Likewise, Black students often looked to the community for churches, barbers and restaurants that felt familiar.

Mainly, Taylor immersed himself in his studies, particularly in the Air Force ROTC program — a place where his talents, not his skin color, helped him stand out. “That’s where I found my niche at Notre Dame,” he says.

He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in government and international relations and joined the Air Force, which soon sent him back to Notre Dame to earn a master’s degree.

Taylor enjoyed his years in military service but acknowledges that the Air Force back then, like Notre Dame, had not fully embraced racial equality. For example, when he pursued his first major posting, he was told that no Black officer had ever served in the counterintelligence office.

“Well, I guess I’ll have to be the first,” he recalls saying.

His career and family — his wife, Constance, and their three children — kept him focused. Two unusual lessons from campus reverberated along the way.

One came from a discussion in an ethics class about Aristotle’s emphasis on a contemplative life.

“He saw that the search for knowledge and wisdom bring happiness,” Taylor says. “That has always stuck with me. It’s guided me through my military experiences.”

Another lesson came from rallies at Notre Dame in May 1970 after four students were killed by National Guard troops at an anti-war demonstration at Kent State University. Some colleges, afraid the rioting would spread, went into lockdown. Notre Dame’s leaders knew violence was a possibility but felt universities must be a place where students and faculty can share their views.

“They decided that something bigger was going on that Notre Dame had to be a part of,” Taylor says. “We have to be engaged when issues are of great importance.”

It wasn’t until 2005, during his post-military career, that he really reconnected with Notre Dame. General Electric, where he was the chief security officer, expressed an interest in recruiting Notre Dame students, and that became part of his mission. Soon after, he became an adviser to the school’s graduate programs.

The bigger step came in 2017, when he was named an executive fellow in the Keough School of Global Affairs. Maura Policelli, executive director of Keough’s Washington, D.C., office, says Taylor teaches two policy labs for undergraduates, sharing his insights into national security and on conflicts and counterterrorism in fragile states. He mentors, advises and guides students and alumni. Policelli co-teaches one of those labs and is a big fan of Taylor’s.

“His tremendous experience in the military as well as at the State Department make him a great mentor for our global affairs students, many of whom are interested in public service,” she says.

There may be some irony in the fact that Taylor, who learned resilience to survive his undergraduate years, is so generous now in helping University students and alumni. Even though

Notre Dame didn’t make it easier for him, he says, it was where he learned how to grow.

Were those the best four years of his life?

“No, but they were a good four years in terms of developing my own maturity,” he says. “Notre Dame taught me how to be a man and gave me the confidence to be all that I could be.

“Giving back to Notre Dame for all that I have received is a big priority for me. I guess I could’ve [taught at] Georgetown or American U., but returning to my alma mater to help the new generation falls in line with my ideas about giving back.”

Ken Bradford is a freelance writer and former reporter at the South Bend Tribune.