Editor’s Note: Nostalgia for a bygone era infuses the national character — often harking back to the 1950s as a symbol of America at the height of peace and prosperity. In this Magazine Classic from 1999, Notre Dame sociologist Gene Halton removed the rose-colored glasses to take a more clear-eyed view of the period that sowed the seeds of tumult to come.

A couple years ago I was playing blues with a group of musicians in their 20s, and with former Muddy Waters drummer Willie “Big Eyes” Smith, who is in his 60s. As I looked around the stage, I realized that the hair and clothing of the young musicians were right out of the 1950s, the guitars and amplifiers were from the ’50s, the music was all that ’50s early Muddy Waters sound. The only giveaway that this was not the 1950s — other than that the young musicians were white — was Willie Smith, who was dressed in a more contemporary shirt. Now Willie was in fact the only person there who really was from that Muddy Waters era.

For a decade that was supposed to be about conformity and blandness, this picture didn’t fit. Forget the nostalgic images carried by TV reruns. Think instead about the flowering of Chicago blues in the ’50s. Then think of jazz — of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and John Coltrane — and the birth of rock ’n’ roll, of the “spontaneous bop prosody” of the beat generation, of the explosive sexuality of Marlon Brando and Marilyn Monroe, of the invention of “the pill,” of murdered Emmett Till and wronged Rosa Parks and the rise of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., of Ralph Nader putting the brakes on the auto industry and Rachel Carson’s breakthrough environmental book Silent Spring, of the harvest of sociological books critical of the times — David Riesmann’s The Lonely Crowd, William H. Whyte’s Organization Man, C. Wright Mills’s White Collar and The Power Elite, Sloan Wilson’s novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit — and of Dwight Eisenhower’s invention of the term “military-industrial complex.” When you think of these things and of other phenomena mistakenly linked to the 1960s, you begin to realize a lot was going on in the ’50s.

Megatechnic America

The 1950s was a time of fundamental transformations in American society, a time when the United States went fully megatechnic. In other words, since World War II, America has been running on the hierarchical system requirements of a machine. Though this same era gave birth to a generalized economic prosperity in the United States, to the civil rights movement and to feminism, the magnification of bureaucratic-corporate structures in that postwar prosperity has ultimately restructured America against the basic requirements of a democratic community. The hugely increased power of military, corporate-industrial and “big science” institutions developed during the 1950s signaled the transformation to megatechnic America, with hydrogen bombs, automobiles and televisions as key symbols of that transformation.

The predicament of America after the war was an enviable one: a victor whose country was physically untouched by the ravages of war, in sole command of devastating nuclear weaponry, launching into an age of unmatched prosperity. All the powers of American technical know-how had pulled together to win the war and now were poised to move on to the promised land that scientific-technical progress would make possible.

The automobile industry and its efficient mass-production techniques ushered in by Henry Ford decades earlier had been instrumental to the Allied victory. But the postwar era saw the firm establishment of the cult of the automobile, led by an auto industry creating ever bigger, more powerful, inefficient and unsafe autos — “the gas-guzzling dinosaur in the driveway” as then American Motors President George Romney called them.

In that isolate Manhattan of the desert, there was an atomic epiphany, not simply the bomb of the initial “Trinity” test near Los Alamos that caused physicist Robert Oppenheimer to quote from the Bhagavad-Gita, “I am become Death, destroyer of worlds,” but the construction of scientific socialism in America. The very bomb that would protect the United States from communism would be the center of a centralized, secret bureaucracy, which, like communism, tolerated no criticism of its ideology, its economics, its disinformation.

Over the course of the Cold War, this scientific-military-industrial welfare state would suck massive resources into its ever-growing belly, and help define the addiction of universities to government funding. Enormous resources were channeled into basic scientific and computer research by the military, justified by fears of Soviet totalitarianism, but also pursued for domestic power, money and because there was a buoyant culture of scientism that most Americans ardently believed in. Science was achieving remarkable breakthroughs, and it seemed to many that there were no limits to progress.

The Bomb as God Symbol

Did you ever hear about the secret nuclear war conducted by the United States and the Soviet Union? Well, nobody calls it that, despite the massive numbers of deaths it has caused. It has been an odd kind of war, a hot war conducted by each side in secret against its own populations in the name of national security. And it is a war far from being over.

At some nuclear tests, U.S. servicemen crouched in trenches one or two miles from ground zero. And the bombs bursting in air gave proof in the night of infernal light: the soldiers, eyes closed, literally seeing the bones in their hands and arms covering their faces. In Countdown Zero, Second Lieutenant Thomas Saffer, who was three miles from ground zero writes: “I was shocked when, with my eyes tightly closed, I could see the bones in my forearm as though I were examining a red X-ray.”

A flood of materials released in the 1990s revealed that thousands of American families living near bomb-making factories and reactors, such as those in Fernald, Ohio, and Hanford, Washington, were exposed to appallingly high levels of radiation. Although the government of the United States claimed that there was no health hazard, it did know the dangers.

Public health officials knowingly allowed uranium miners to breathe polluted air while they studied them, rationalizing that the increased lung-cancer deaths from lack of breathing masks were the cost of keeping the mining secret from the Russians.

Dr. Victor E. Archer, the principal investigator for the study from 1956 until he retired from the Public Health Service in 1979, stated in a 1990 letter to me, “Although I recognize that what I did was the only real way to achieve control of the hazard, I am not especially proud of it, since many lives were sacrificed. But that has frequently been the way of human progress — some must be sacrificed for the greater good of all. This has been true in war and peace. Modern ethics and morality may soften this path to progress, but only at the cost of slowing the process.”

The war he refers to was the undeclared Cold War, advent of the age of undeclared wars, the war where $5.5 trillion was spent on nuclear weapons alone. Meanwhile, the CIA, FBI and other agencies were suppressing Americans’ freedoms and rights under a mantle of national security.

Physicist Edward Teller is a classic study of scientific arrogance in the 1950s. Resentful of the director of the Manhattan Project, Robert Oppenheimer, who resigned a few months after the atomic bombs designed by the project successfully ended the war, Teller attempted to discredit him in public testimony and in secret interviews with the FBI.

While Oppenheimer was being discredited, scientists Wernher von Braun and Arthur Rudolph were rising in the American rocket program, thanks to the secret OSS “Operation Paperclip,” which cleansed the files of ardent Nazis brought to the United States at the conclusion of the war. Von Braun, whose V-2 rockets rained terror on London during the war and who was immortalized in a Tom Lehrer song: “Once rockets go up, who cares vhere zey come down, zat’s not my department, says Wernher von Braun” — went on to become the assistant director of NASA in the 1960s.

Rudolph, who tortured numerous victims in Dachau concentration camp to death in doing pressure chamber aviation studies — pressurizing them until their lungs burst — went on to design John Glenn’s spacesuit. He was allowed to return to Germany in the late 1980s when the state department finally raised questions about his mass-murder war crimes.

Edward Teller could play the role of objective scientist well, but he was intensely vindictive toward anyone he perceived as standing in his way. He took Oppenheimer’s reservations about the development of the hydrogen bomb as a personal attack. In the midst of the McCarthy era, on March 1, 1954, a hydrogen bomb developed under Teller’s supervision was detonated on Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific. About a month later, Teller publicly denounced Oppenheimer as a security threat in a political show trial put on by the Atomic Energy Commission and its director Lewis Strauss. That trial resulted in Oppenheimer losing his security clearance, effectively barring his participation in nuclear weapons issues and research. The only real threat that Oppenheimer posed to nuclear power mongers was that he was a patriotic scientist with a conscience.

With the displacement of Oppenheimer by Teller, we see the corruption of morally concerned science by the mentality of the self-aggrandizing ego, a crucial ingredient in the building of Megatechnic America in the ’50s. Little power lords with huge egos were attempting to establish themselves across the board: Senator McCarthy and his paranoid witch hunts, J. Edgar Hoover and his use of the FBI as a secret police, Robert Moses and his paving of New York City.

Consider Ray Kroc’s politics of the franchised hamburger business, a view expressed best in his own words, “The organization cannot trust the individual; the individual must trust the organization.” Kroc’s statement defines the new creature coming into being in the ’50s, what William H. Whyte titled Organization Man. Mechanized standardization bestowed by benevolent bureaucracies would be the means by which mobilized citizens could drive themselves in their new autos on their new highways with their new motels and their new fast food joints, and eventually their new privatized public shopping zones, to the New Jerusalem of conformist Megatechnic America. But if you make a world more and more machine-like, you run the risk of making yourself more and more machine-like. What was so perplexing for organization man, as Whyte noted, was that, “[I]t is not the evils of organization life that puzzle him, but its very beneficence . . . What it does, in soothing him, is to rob him of the intellectual armor he so badly needs.” Megatechnic Russia brutally terrorized its people into submission, but Megatechnic America would reward its people into submission, through an unprecedented material abundance. Consider one example from the “plowshare” project to use nuclear bombs for peace and prosperity.

Teller propagandized heavily for a demented project cooked up at his Livermore laboratory in the late ’50s to set off a series of detonations in Alaska near Point Hope and create a new international harbor. The test also secretly intended to study the effects of fallout on the ecosystem — which would include the Native American “elements” of that ecosystem, the people of Point Hope, 30 miles north.

Documents uncovered decades later by Daniel T. O’Neill reveal that the Atomic Energy Commission poured in more than $100,000 in grants for biological studies to the University of Alaska — big bucks in 1959. But as those studies pointed to the devastating effects the explosions would have, university officials pressured, censored and fired researchers, and rewrote their reports.

The many impracticalities of Teller’s Project Chariot, not to mention the human costs that the Atomic Energy Commission and Livermore officials sought to suppress, failed to attract the funds needed. Though the project officially fizzed, a few scientists working for the AEC secretly released almost 45 pounds of highly radioactive waste, from a recent Nevada test, along the creek that ran into the proposed harbor, “to determine the extent to which irradiated soil would dissolve the fallout radionuclides and transport them to aquifers, streams, and ponds,” writes Paul Boyer in Fallout: A Historian Reflects on America’s Half-Century Encounter with Nuclear Weapons.

Test done, the efficient scientists buried the now 15,000 pounds of contaminated soil and left without a word of warning to the inhabitants. Presumably faraway Native American guinea pigs would not become as visible as the inhabitants of, say, Saint George, Utah, where heavy fallout fell even when weather conditions were “good” at the Nevada test site. John Wayne, Susan Hayward, Agnes Moorehead, Dick Powell and an abnormally high percentage of other cast and crew members of the 1956 film The Conquerer, shot in the desert outside Saint George, died of cancers, statistical casualties of the American nuclear war on itself.

Current estimates of deaths due to nuclear bomb testing in the United States easily exceed the number of Americans killed in the Korean and Vietnam wars combined, including significant numbers of children. A recent book, Atomic Audit, gives what is likely a conservative range of 70,000 to 800,000 deaths worldwide due to American fallout alone, to which must be added deaths in high risk populations and their offspring, such as the almost 600,000 workers in the nuclear weapons complex, the 220,000 military personnel who participated in atmospheric tests, those citizens who lived downwind from nuclear weapons plants, and the more than 23,000 men, women and children who were subjects of radiation studies, often unwittingly.

What one sees in the nuclear culture of the ’50s, in its arrogant scientism, in its effects on political, popular and commercial life, is the scientific materialization of ultimate power, of God. Early in the century, Henry Adams had shown the connection in The Virgin and the Dynamo, where he argued that the electric dynamo had taken the pivotal place in society that the virgin held for medieval Europe. As early as 1905, he sensed the implications of the release of increasing forms of power, unmatched by moral controls, saying that it would not take another half-century for there to be “bombs of cosmic violence.”

Godzilla or Guernica?

At the drive-in movies my parents took me to in the ’50s, as sunset gave way to darkness over New Jersey, all the children ran terrorized from the playground located just under the giant screen, knowing that momentarily Godzilla or Rodan or some other menacing prehistoric nuclear terror beast would be looming above them.

Those monstrous beasts were the primal, reptilian darkness that civilization was supposed to repress, now suddenly released into consciousness. The Japanese released the gigantic repressed prehistoric beasts — tyrannosaur and pterodactyl — while postwar America tended to release horrendously enlarged insects — ants in the film Them! or grasshoppers attacking Chicago in The Beginning of the End — and radioactively enlarged or shrunken humans. The Incredible Shrinking Man began his shrink after a nuclear cloud passed by his boat — an event strikingly similar to the thermonuclear dousing of the Japanese fishing boat The Lucky Dragon during the hydrogen bomb tests on Bikini Atoll. The Amazing Colossal Man was titled after an American soldier who began to grow uncontrollably after being overdosed at a nuclear test site while trying to rescue civilians, ultimately enlarging into a demented monstrosity. This film expressed in crude grade-B form what the U.S. government could never admit: Soldiers really were disastrously overdosed, unlimited power really was like an uncontrolled cancerous growth.

These films were pop culture versions of what much of modern art itself was all about: the release of those extremes of emotion in the outburst of modernism in the early 20th century. In those years avant-garde music ruptured its connections to tonality and painting broke out of the traditions of perspective and representation. Though this art may still seem abstruse to traditionalists, these artists were revealing the explosive energies of the new century, in the barbarian forces of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, Picasso’s cubism — and later, of his epic painting of the first use of saturation bombing by the Nazis, Guernica. But both in these artistic breakthroughs of modernism and in the pop low-budget effusions of the ’50s films there was a picturing of energies released that transcended pure power per se: Stravinsky and Picasso harnessed the energies in their showing of them, the sci-fi films were morality plays about the dangers of unharnessed power.

Return from Pleasantville

Why do the 1950s represent a golden age to many Americans? There was a genuine flush of optimism from the postwar age of prosperity America had embarked on. But does that explain it? Or is it an overdose of ’50s sitcoms endlessly projecting those images of “swell times”?

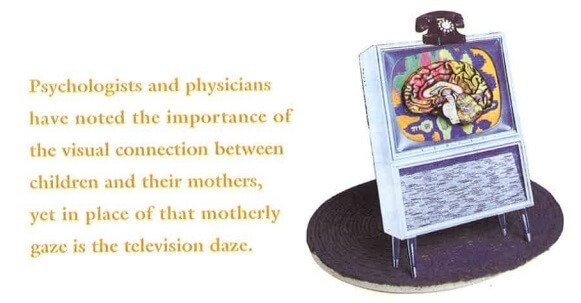

With the advent of television, viewers came to feel personal connections to images performed by actors, celebrities, politicians. Families gathered around their new televisions to watch projected images of families where all serious conflicts were removed and where the problems that remained could be cheerily resolved at the end of the half-hour. Swell times.

The recent film Pleasantville explores this nostalgic view of the ’50s, and of how its idealized self-image of perfection, portrayed in reruns of TV sitcoms, is not what it was cracked up to be. Dave, a self-conscious teenager, finds refuge from the arguments of his divorced parents and from the traumas of high school in the ’90s through his fascination with reruns of a ’50s sitcom. With his mom gone for the weekend and his dad refusing to visit, Dave wants to watch the all-weekend rerun festival of the show. But a fight with his popular sister, who wants to watch MTV, ends with both of them projected into the black-and-white world of the series. Now they are “Bud” and “Mary Sue,” an unbearable situation for his sister but clearly relished by “Bud.”

In this kitsch-world, the families are all intact and all white, the high school basketball team never loses, there is no sex and there is no real feeling. It is a kind of reverse version of the film Invasion of the Body Snatchers, in which the citizens of a small town are gradually replaced by alien pod-spawned versions of themselves, physically exact but emotionally neutered. In Pleasantville, thanks to the intrusion of Bud and Mary Sue and their ’90s view of things, people begin to change from a condition in which they are shielded from experience to one in which they are emotionally present. They literally become “colored,” changing from black-and-white, manikin-like conformists, to being able to see and feel the world for all its color — a process that causes “racial” resentments to explode by the black-and-whites. Interestingly, however, Bud and Mary Sue are among the last to change, showing that even the sexual liberty that Mary Sue exhibits and the worldly savvy Bud possesses are forms of conformity. The teens are every bit as alienated from true feelings as the Pleasantville people.

This is a movie that highlights the meaning of the spectatorial world TV has made. It beautifully unmasks in comedic form the tragic substitution of the motherly gaze by the mechanical eye of television. Psychologists and physicians have noted the importance of the visual connection between children and their mothers in the earliest stages of development, especially for the emergence of the self and of empathy. Yet in place of that motherly gaze is the television daze, the development of a relationship based on the apparent attention the TV projects on to the viewer. Ultimately Bud, the TV junkie, discovers that feelings, even painful ones, are better than TV fantasy anesthesia, and he brings this insight back to his real-world life.

In the 1946 film It’s a Wonderful Life, Jimmy Stewart’s character, depressed and suicidal, experiences a vision of what it would be life if he had never been born. His small town becomes a glittery sin-city, Pottersville, named after the heartless town millionaire. Stewart’s character sees that his job as town banker has been crucial not only for the economic welfare of his neighbors but in keeping the community spirit alive. He returns from his hopelessness, renewed as the solid-guy-who-holds-the-town-together, and succeeds in the end in staving off Pottersville. Decency overcomes unbounded capitalistic greed and human baseness.

Unfortunately Main Street in Megatechnic America has been replaced by malls and other versions of Pottersville. In place of the gaze and its empathy, the world of television has produced a Pleasantville of the soul in America, a culture in which one’s identity is supposed to be completed by acts of consumption.

The other side of optimism

It is easy to understand how the cult of perpetual, unlimited progress could flourish in postwar 1950s America, given the outpourings of scientific discoveries, the unprecedented economic prosperity, and the political superpower status the country had reached. But how does one explain the widespread hope that things will get better shared by disenfranchised African Americans in the South yearning for the “promised land” of the North?

In the 1940s and ’50s, millions of African Americans moved north to escape the Jim Crow slave conditions of the South. Chicago, the North more generally, was the “promised land.” In the Deep South a black man was either called boy, or, if older, uncle, but never a man, and could neither expect political or economic justice nor do anything to seek it without fear of severe retribution.

A drummer from South Bend, Bill Nicks, who in the mid-’50s founded the band that would later record on Motown as Junior Walker and the All-Stars, told me how his family moved to South Bend from Greenwood, Mississippi. One day the owner of the plantation threatened to beat his father, and his father stood up to him, forcing the owner to back off. His father also knew that if they did not move that very night, he would likely be killed.

Some of these struggles were also recorded in the blues that found expression in Chicago in the 1950s. If Jimmy Reed’s song Big Boss Man called attention to racism (“Big boss man, can’t you hear me when I call?”) and ironic ways of answering it (“Well you ain’t so big, you just tall, that’s all”), then Muddy Waters’ Hoochie Coochie Man and Bo Diddley’s I’m a Man celebrated the relatively freer conditions. At least in the North a man could call himself a man while still being subjected to racial prejudice.

The success of the Muddy Waters band, whose members all came to Chicago from the Deep South, was unexpected — no one imagined that the raw country sounds of the delta would catch on in the sophisticated Chicago scene. But with the flow of immigrants from the delta after the war, the earthy intensity of delta life was transformed into the music of the promised land.

In the ’50s there was an unprecedented flowering of blues and jazz and rhythm ’n’ blues. Perhaps it was simply the energies released by the war and by the massive migrations, but whatever the case, the effect was sheer vital efflorescence, and it occurred, interestingly enough, when avant-garde “classical” music (which highbrows unfortunately call “serious music”) was going belly up.

Jazz also blossomed in the 1950s. Begun by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and others in the 1940s, developed further by Miles Davis, John Coltrane and many others in the ’50s, bebop jazz found whole new means and moods of expression. Through unselfconscious collective improvisation — the very lifeblood of African-American tradition — it managed to speak a new language that was a genuine emergent of American culture. Perhaps of all the avant-garde art movements after World War II, bebop jazz best exemplifies the aesthetic of spontaneity, particularly “spontaneous bop prosody,” the ways words speak musically.

Segue to spontaneity

There was a powerful influence of jazz on well-known beat writer Jack Kerouac, and he and other beats drank heavily from the Dionysian fountain of bebop phrasing, breathing and being.

The spontaneity that jazz embodied also found its form in avant-garde painters, writers and poets in the ’50s, such as poet Charles Olson (and other Black Mountain College artists), and in beats Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. Kerouac and Ginsberg, plus beat from the street, Neal Cassady, formed an unlikely trio of the ’50s.

Cassady, the street kid from Denver, appeared to the beats as a natural born con man and felon, mesmerized, I believe, by the literary versions of himself he found first in Kerouac and then, in the 1960s, in Ken Kesey. Cassady was like the dark mirror Kerouac could hold up to see himself in anti-idealized and even a kind of gregarious, anti-social form.

If Kerouac showed Cassady the higher life of writing, then Cassady showed Kerouac the high life he never knew could exist in such intense, supercharged form. Cassady, who as a 13-year-old once hitchhiked and joyrode his way to visit Notre Dame, was the fast-talking, street-wise hipster who found his doppelganger in Kerouac’s football-playing, athletic-literary fusion.

I suspect that Cassady found this same connection later with Kesey’s wrestler-writer fusion: Here were guys as nimble on their feet as he was, who also could sweat those vitalities into their writings, producing visceral, palpitating depictions of America released from the dead Puritan grip. These were New World V-8 explorers, racing and conniving and screwing their way past all known speed limits, drugged with desire to live in the New Jerusalem of the uninhibited Holy Now: a no-holds barred, free-style wrestling match with the demons of the fates.

Take that wistful rhapsody which ends On the Road:

“So in America when the sun goes down and I sit on the old broken-down river pier watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls into one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast, and all that road going, all the people dreaming in the immensity of it, and in Iowa I know by now the children must be crying in the land where they let children cry, and tonight the stars’ll be out, and don’t you know that God is Pooh Bear? the evening star must be drooping and shedding her sparkler dims on the prairie, which is just before the coming of complete night that blesses the earth, darkens all rivers, cups the peaks and folds the final shore in, and nobody, nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old, I think of Dean Moriarity, I even think of Old Dean Moriarity the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarity.”

Kerouac and Cassady — “Sal” and “Dean” — were a buddy movie unto themselves in On the Road (1957), but Kerouac was a man of other moods and contradictions as well. When his spontaneous prose is on the mark, you feel the mood of his wild holy quest, whether it be a jumping jazz joint he is describing or the roadway epiphanies. He wrote from mania, often amphetamine or caffeine driven, but Kerouac seemed in the end to be trapped by his depressive demons, his alcohol, his lost youth.

Did the beats find the New Jerusalem, or were their very impulses to jettison the inner editor of consciousness to go go go fast fast fast, to live in a limitless present, simply the subjective side of what rational, progressive corporate structure was undertaking with its fast cars, fast food, fast information, fast housing, fast suburbs, and oh-so-fast missiles?

In the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock, painting, literally, as an activity rather than an image, took precedence. In a strange way Pollock “pictured” the culture of go! of go man go! of America on the move. But to my eyes, the vigor of abstract expressionism’s “energy field” paintings, developed in the ’40s, had dissipated by the 1950s at the very time the artists were being anointed with success. Abstract expressionism unnecessarily excluded other elements of what it means to paint; it proscribed the past and the image as possibilities. It could turn into a mere exercise of technique — of the technique of spontaneity — every bit as much as the culture of abstraction it was supposedly a reaction against did.

Perhaps the elevation of the very concept of “advance-guard” as a guiding ideal of modernism, rather than a fact that happens to occur in history, an ideal that took the progressive jettisoning of the past in the name of originality as historical necessity, had to culminate in something like abstract expressionism, in what could be called “the last gesture of painting.” It found its originality in the gesture of painting itself, and soon found itself painting into a corner by that very same gesture. True spontaneity, as the jazz musicians of the ’50s well knew, deeply involved past and future in the moment. But like the apocryphal story of the beatnik who when asked “How do you get to Carnegie Hall?” responded, “Practice, man, practice!” spontaneity involves repetitive, day-in-day-out crafting. Like the musical scales John Coltrane would play endlessly in rehearsal, even between sets at a gig, the spontaneous gesture is a culmination of a practice rather than a starting point.

That thing called freedom

When I remember that gig with Willie “Big Eyes” Smith and the twentysomething retro musicians two years ago, I think of that thing in America called freedom, of the great hopes and feelings in the 1950s that everything was possible, and the various ways the limits of those ideas showed themselves and will yet show themselves. Yes, those crazed, conformist, contradictory times of the ’50s have found their ways very much into the present, even if that message of freedom has been formatted all too fatally into an evaporating mirage.

In thinking of the ’50s, it may be good to remember that freedom was something very much in the air from a variety of perspectives — cold warriors, civil rights seekers, nascent feminists, teens cruising, artists seeking it or celebrating it through their work. Because today the very idea of freedom seems to have been reduced to that of the “freedom” to consume, to a consumption culture that truly found its form in the automaniacal, franchising ’50s.

Take the brainwashing of children and their parents by television — by thousands upon thousands of commercials, whose basic physiological stimulus-response formula consists of acts of anxiety relieved by the purchase of a commodity, and by thousands of acts of unfelt violence, by endless images of overflowing magical luxury, by a world of disposable celebrities who provide the children who identify with them substitute emotions the same way that drugs promise substitute feelings. Buy me, eat me, drink me, drive me, and you can be spontaneous, says the new Moloch of Megatechnic America. This is the reality of early education in America — mind-altering electro-chemical indoctrination — and why students too often can tell you everything about I Love Lucy and Friends, while remaining clueless about the whys and whens of real history.

The 1950s set into motion — with its autos and televisions and franchises and “military-industrial complex” — an increasingly Megatechnic America, a machine that rules today increasingly on automatic.

But there are those vast vitalities that poured out of the 1950s, producing in a Rosa Parks or a Robert Oppenheimer or a Jack Kerouac, enduring road maps of what America could be, “all the people dreaming in the immensity of it.”

Eugene Halton, a professor of sociology at Notre Dame, is the author of Bereft of Reason and Meaning and Modernity (both with University of Chicago Press), and co-author of The Meaning of Things (Cambridge University Press).