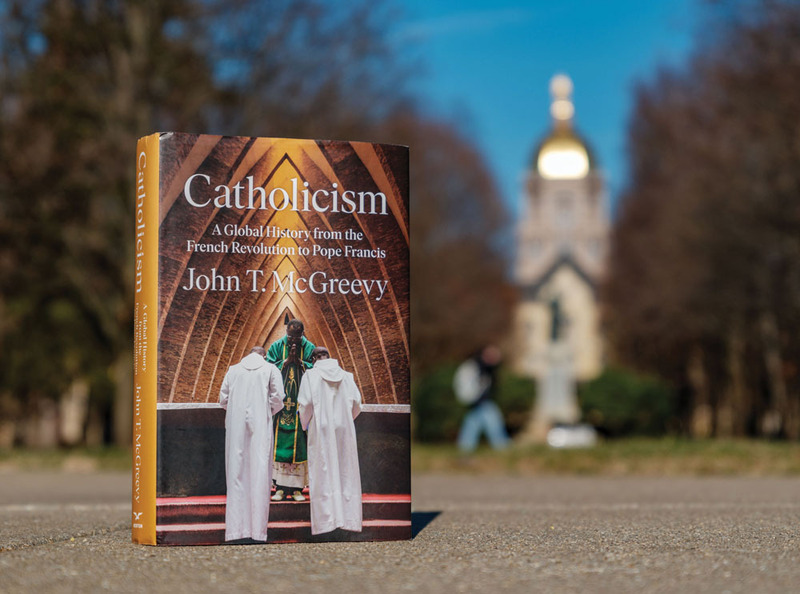

Matt Cashore ’94

Matt Cashore ’94

There’s nothing new about disagreement within Catholicism. Historian John T. McGreevy’s new book, Catholicism: A Global History from the French Revolution to Pope Francis, begins with a life-and-death disagreement during a most consequential event — one that defined the terms and tone of the 19th and 20th centuries.

In McGreevy’s telling, two Catholic priests stood on opposite sides of the rapacious violence that marked the Reign of Terror in Paris in 1793. The first, an Irish chaplain to the deposed King Louis XVI, blessed his patron at the scaffold and was sprinkled with his blood when the executioner showed the head to the mob.

The second, a Frenchman, chaired the assembly that voted to execute the king. Abbé Henri Grégoire had described as “based on the gospels” a French law passed two years earlier that gave citizens the authority to select bishops and priests and required all priests to take an oath of loyalty to the revolutionary government.

The two clerics exemplify for McGreevy “a debate about the relationship of Catholicism to the modern world that began in the early eighteenth century” and continues today. The ultramontanists, represented by the Irishman who fled to safety in England of all places, looked “over the mountains” to Rome and the papacy as “the primary source of Catholic authority.” Reform Catholics like Grégoire wanted a reasonable religion that conformed with “Enlightenment ideals of science and investigation” and preferred episcopal and even lay authority to that of the pope. They downplayed pious devotions and missionary efforts and looked askance at religious orders, especially the Jesuits, whose vow of obedience to the pope supposedly put them at odds with loyalty to the local.

These vast, adversarial inclinations were often fluid, sometimes overlapping, always hard to define. Further complicating matters, Catholicism’s uneasy relationship with itself mirrored the Church’s shaky relations with virtually every form of secular authority around the world during two centuries of political experimentation, revolution and war.

Several popes showed interest in certain kinds of reform, both within and outside the Church. And it was possible to be an ultramontane liberal — traditional in religious practice while embracing democratic government. Consider Father Edward Sorin — an example McGreevy doesn’t cite — who built a little piece of Catholic France in the American Midwest and visited Europe dozens of times and Pope Pius IX at least once, all while sending off chaplains and nurses to support the Union during the U.S. Civil War and dedicating a hall for theatrical and civic celebrations to George Washington.

This is not another book about the Christian West. McGreevy’s concern is Catholicism’s reckoning with global changes — wars, migration, the fall of monarchies, decolonization, evolving mores, interreligious competition, climate change, its own moral corruption — and the enduring responsibilities the Church accepted when the first missionaries left Christendom in earlier centuries.

McGreevy ’86, one of the leading Catholic historians of our time, spins the globe with every paragraph, often from one line to the next. He frames most chapters with the story of a Catholic whose life typified the moment. Mbange Akwa, the German-educated son of an elite Cameroonian family, became a sensation at the 1888 German Catholic Congress in Freiburg, an exemplar of a period when empire and evangelization seemed harmonious. Edith Stein, the German Jewish philosopher and convert today venerated as St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, illustrates the Church’s dilemma when the world the ultramontanists had momentarily won over descended into nationalistic darkness.

Jacques Maritain is a central figure. A scholar of St. Thomas Aquinas, Maritain left behind the far-right politics of his early career, followed Pius XI’s condemnation of France’s monarchist movement and began to make neo-Thomist arguments favoring democracy. His 1936 book Integral Humanism became “one of the key documents of twentieth-century political thought,” a bible of sorts for Christian Democrats in Europe, Africa, Asia and Latin America for decades after World War II.

By the time the Second Vatican Council convened in 1962, reform-minded theologians like the young Joseph Ratzinger believed that, in McGreevy’s words, “Europe’s plunge into the abyss of two world wars had discredited any notion of Western superiority.” After the council, with faith fading in the developed world and blossoming in the Global South, a different German theologian may have been channeling Senegal’s president Léopold Senghor or the Japanese novelist Shusaku Endo, both Catholics, when he wrote of a Church aware of itself as “no longer a European export.”

Disagreements over authenticity still flourish within the Catholic Church of 2023, but it has other problems. One is its confrontation with other religions as it grows in Africa and Asia. Another is the hierarchy’s repeated, profound abuses of authority and trust as it attempted to conceal clerical sexual misconduct the world over.

Catholicism demonstrates how the Church since 1789, even when living by its highest ideals, could not have hoped to stand on the right side of every issue all the time. The pace of change was too swift, the issues too complex. McGreevy makes those changes and the Church’s modern development understandable, the task he set for himself on page one. “No institution is as multicultural or multilingual, few touch as many people,” he points out. Other organizations may possess formidable influence; only Catholicism counts 1.2 billion baptized members, most of them “people of color living in the Global South.”

Last year, McGreevy became provost of a Catholic research university aspiring to global preeminence. Well over one-third of Notre Dame freshmen are Americans of color or have matriculated from abroad. In Catholicism, McGreevy has done his homework as the center of Catholic gravity shifts toward the equator and beyond.

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.