The naturalist Clarence Birdseye never met an animal that he didn’t want to devour.

Working for the U.S. Biological Survey out West in the first decade of the 20th century, Birdseye learned to trap and cook field mice, chipmunks, gophers. He dined on woodchuck, beaver and porcupine. Among his favorite meals was rattlesnake fried in pork fat, which tasted, according to Birdseye, “much like frog legs.” When he wanted a real treat, he might cook up some skunk.

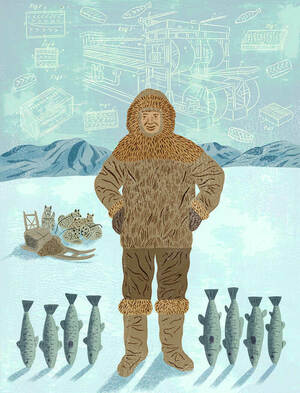

The eating got even better when Birdseye relocated to Labrador in 1912 to seek his fortune in the fox-fur trade. He and his wife built a house in Muddy Bay, and Birdseye began traveling by dog sled up and down the Labrador coast, learning all he could from the self-reliant locals about fox breeding and the rugged North. The long subarctic nights he spent writing in his journal. He wrote, more than anything else, about what he ate. Otters. Martens. Muskrats. Any kind of bird he could stick a fork in. “Good Lord,” he enthused in a letter, “how fine gull gravy tastes!”

Birdseye had some of the qualities of a 21st-century foodie — adventurous tastes, an appetite for the local, a compulsion to talk at length to anyone who would listen about what he had just eaten for dinner.

“I arrived by dog team at the North West River,” he wrote to a friend, “and, after thawing out, sat down to one of the most scrumptious meals I ever ate. The pièce de résistance was lynx meat, which had been soaked for a month in sherry, pan-stewed, and served in a brown gravy.”

But for all the wild stuff Birdseye happily consumed, it was his Labrador encounters with cod — that most homely and common of staples — that would forever change his life, and ours. Birdseye had noticed that Labrador’s indigenous fishermen froze their catch in the frigid open air. When it was truly cold — say, minus 35 degrees Celsius — the cod were “frozen in mid-flip,” Birdseye marveled. He also noticed the fish tasted great when thawed days or even weeks later.

As Mark Kurlansky notes in his excellent 2013 biography of Birdseye, that deliciousness was a surprising contrast to the frozen foods Birdseye had encountered back in New York, which tended to turn mushy and unpalatable, if not outright dangerous, upon thawing.

How did the locals do it? How did they produce a frozen fish better than anything he had eaten in the big city? In working out the answers to those questions, Birdseye helped change the way the world ate. You don’t often find his name among A-list world-changers; he’s seldom ranked with the likes of Edison or Ford. As titles go, Father of Frozen Food is less than heroic.

But by making food a product that could be preserved, packaged, shipped and sold on an industrial scale, Birdseye did something singularly impressive and very American. He gave us a way of eating that satisfied both our appetites and our Puritan fear of wasting time. Birdseye made food that most modern of things. He made it convenient.

I was born into the great midcentury flowering of convenience foods, the age of the TV dinner, instant coffee and Cool Whip. My parents still practiced that quaintest of rituals, the nightly family dinner, and it occurs to me now that I have never given them enough credit for this expression of devotion to the family, because sharing a table with four ill-mannered kids after a full day at work couldn’t have been their idea of fun. Getting everyone fed in a timely manner and avoiding major inter-kid disturbances meant sometimes giving in to the lure of convenience. Frozen fish sticks were an occasional offering at our dinner table, especially during Lent. The association between the season and frozen food remains so strong for me that to this day, I cannot open a freezer door without feeling residual pangs of self-reproach and contrition.

Those fish sticks were the direct culinary descendants of the frozen cod fillets that Birdseye first produced, inspired by his experiences in Labrador. But the convenience-food industry has in the intervening years only grown more ambitious. Where Birdseye was interested mainly in preserving perishable food so that it would maintain its flavor, the goal now is often to alter the very shape and character of food, to make it more portable for consumers on the move. Americans now eat most of their meals away from home or on the go, a fact that explains the popularity of products like Go-Gurt. One in five American meals is consumed in a moving car, so entire repasts are now packaged to fit in cup holders (the category is called cup-holder cuisine, of course). Birds Eye, the brand fathered by Clarence a century ago, recently offered an applesauce that could be squeezed from a tube like Play-Doh, presumably directly into one’s mouth. With convenience food, one has no need for a dining room table, no need for a knife and fork and, for that matter, no need for other people.

Convenience is so much a part of our lives that we tend not to think about it. (To the British, a “public convenience” is a bathroom, and it doesn’t get much more mundane than that.) We have become connoisseurs of convenience, seeking out and paying a premium for homes that are conveniently located, dinners that are convenient to prepare, flights that leave at the most convenient times. Convenience has a funny way of starting out as a means to an end and very quickly becoming the end itself. Similarly, convenience never satisfies us for long, because it soon becomes nothing more than an expectation, a necessity even. When, stranded at home by the pandemic, I learned that Amazon Prime would bring just about anything to my front door, and bring it now, I was briefly amazed. Now it just registers as the natural order of things.

For all its everydayness, convenience is also utopian. It claims to saves us time and labor, thus freeing us for more noble and enjoyable pursuits like, say, conversing with our children or (more realistically) binge-watching Fleabag. Life in the future is always imagined as more convenient. See The Jetsons, with its holograms, flying cars and robot housekeepers. The fact that much of the technological promise of The Jetsons has been realized, and yet we are still binge-watching Fleabag, should prompt skepticism about just how much convenience has to offer us.

Convenience’s etymological roots are in Latin. Convenire means “to agree or come together” and is the root of the English word convene. When it first appeared in English in the 14th century, “convenient” meant “fitting” or “appropriate.” Our modern sense of convenience emerged only later, and it took capitalism to make it one of our defining values. Saving time and labor, promoting comfort and ease — convenience in these senses comes to us as an inheritance of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the age of a fully matured industrial capitalism — and also the very years when Birdseye was roaming the wilds of the rugged West and frozen North, eating everything he could catch.

Industrial efficiency was the official philosophy of the time, the quasi-scientific notion (believers dispensed with the “quasi”) that precise measurement and management would boost productivity and therefore the general welfare. Frederick Winslow Taylor was then introducing scientific management to factories, and Henry Ford was adapting Taylor’s timesaving ideas to his assembly lines. It was Birdseye’s achievement to apply similarly modern factory principles to the stuff that we served our families for dinner.

It’s not surprising that the United States, with its vast spaces and enormous wealth, became the world capital of convenience. Convenience requires finding the fastest possible way to get across a continent (or even just your city at rush hour) and the easiest possible way to communicate with anyone, anywhere, anytime. Our national mania for hurrying could be traced all the way back to Ben Franklin, who warned us that “wasting time must be the greatest prodigality.” A couple centuries later, Bill Gates was heralding the birth of “friction-free capitalism” on the World Wide Web, the greatest timesaver yet.

Even when we’re just chilling, just killing time, we insist on saving time. Ever-faster Internet connections give us instant access to, for example, video of somebody else’s dog riding a Roomba. Some of us may be old enough to remember dial-up modems, but today not even I could muster the patience to sit through the old 10 or 15 seconds of screeching, multifrequency alien electro-noise just to Google something. Years ago, I frequented a tavern that kept a volume of The Baseball Encyclopedia among the dusty bottles behind the bar to settle sports-trivia-related disputes. I don’t know which is more quaint, the concept of turning to books for crucial information or the notion that late-afternoon dive-bar drinkers were once interested in talking to something other than their iPhones.

The drive for greater convenience is, though, by its nature self-defeating. Set a speed record for the delivery of some product or service and you’ve only created another standard that must be surpassed. And every convenience only creates another inconvenience. The car gave us all more mobility and greater vistas of economic opportunity, sure, but it also gave us lines at the DMV. Or consider the weirdness of shopping for clothes online. Say you like the looks of that sweater, but you’re not sure which size to go with. So you buy the same garment in two or three different sizes and try them all on at home! That free-returns policy of your favorite retailer means you can always send back the unwanted ones. The term for the popular practice of ordering a size up and a size down from the one you think you need is “bracketing,” and it’s one reason why American retailers took back more than $100 billion in stuff purchased online last year. Free returns are a convenience we would not have dreamed of a few decades ago, but along with it comes a glut of returned merchandise that retailers can’t afford to return to inventory, so an awful lot of it ends up in the landfill. Every convenience comes at a cost — and that cost is not always borne by the person enjoying the convenience.

In this way the pursuit of convenience can come to seem like a scam in which you spend all your time trying to save time, knowing you will, inevitably, run out of time, never quite sure what you are saving it for in the first place.

Birdseye had gone to work for the Biological Survey just as the international race to be first to reach the globe’s frozen poles was coming to a climax. Dozens of nations organized expeditions, and their efforts were covered in newspapers like sporting events. The world was becoming a little ice-obsessed, and also more than a little time-obsessed. Rail travel and telecommunications had changed our very concept of time, and the world seemed to be shrinking. The North and South poles remained as the two last terrestrial prizes for explorers, and reaching them seemed just a matter of time.

Even these last grand endeavors of the Heroic Age of Polar Exploration were imbued with the emerging industrial values of efficiency and time management. At about the time Birdseye arrived in icy Labrador, the British Antarctic expedition led by Sir Robert Falcon Scott, brave but ill-prepared, was discovering that the coolly practical Norwegian Roald Amundsen had beaten it to the South Pole by 34 days. On the return trip, Scott and his men, faltering under deadly weather conditions and suffering from poor planning, perished of exposure and starvation just 11 miles short of the shelter and supply depot they had established. Days earlier, an expedition member named Lawrence Oates, fearing that his worsening frostbite was slowing his companion’s progress, had left his tent and walked alone to his death in a blizzard. He told his companions that he was going out for a walk. He added, “I may be some time.”

Birdseye’s experiments in food preservation were themselves concerned with time — with how to stop it, or at least arrest its effects. There was nothing particularly novel, even then, about freezing food to preserve it. People had been storing food in icehouses for centuries. The 17th-century philosopher and experimentalist Francis Bacon is said to have died of pneumonia brought on when he stopped mid-carriage ride to see whether stuffing a chicken with snow would preserve it. Even in the New York City of Birdseye’s childhood, tin-lined wooden iceboxes were already commonplace, one of the first generation of household conveniences that would later seem indispensable.

I was born into the great midcentury flowering of convenience foods, the age of the TV dinner, instant coffee and Cool Whip.

What Birdseye hit on in his post-Labrador experimentation was a way to freeze food that wouldn’t spoil the product — and just as important, the methods for packaging and transporting it for convenience-minded consumers. Pre-Birdseye preservation methods froze food relatively slowly at temperatures not much below freezing. The large ice crystals produced by slow freezing robbed food of flavor and texture, resulting in mushy products prone to rotting. Birdseye’s quick-freezing method produced smaller ice crystals that did less damage to perishable food and worked to preserve flavor and freshness. “The fresh-from-the-ocean flavor is sealed right in!” he promised customers.

The frozen-foods company that Birdseye founded based on these methods became literally a household name. Birds Eye Frosted Foods, as the brand was once known, filled freezers across America. By midcentury, time-pressed Americans were eating 800 million pounds of fast-frozen food annually. I remember the supermarket freezer section of my 1970s childhood as a tundra to be braved on the way to the cookies or Count Chocula. (The other great supermarket microclimate is, of course, the misty rainforest of the produce department.) Your local freezer aisle is now the locus of food innovation; frozen food is one of the fastest growing of grocery categories. Maybe we will one day honor the memory of the inventor of the pickle pop or whoever had the idea to flash-freeze pigs in a blanket. Of course it all started with Birdseye, but it’s funny that an eccentric and adventurous eater like him would have done so much to industrialize the food we consume. And strange also that the frozen-food aisles he pioneered keep expanding, even as the frozen bits at either of Earth’s poles continue to melt away.

The annals of inconvenience probably begin with Adam and Eve. They had all they could possibly want in abundance in Eden, including time, but of course they threw it all away. As punishment for their sin, we have been taught, they were burdened with lives of onerous work. No more ease and comfort, no more convenience. (Their misstep was grabbing an unauthorized snack, which I suppose makes them the first problem eaters.) Needless to say, the twin curses of having too much to do and too little time in which to do it continue to plague some of us. “Wasting time,” Max Weber wrote, “is the worst of sins.” Weber’s classic work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, famously linked religious concepts like original sin with a business culture that valorized efficiency, productivity and promptness.

But even as Weber was writing, others were offering the first critiques of the emerging time-obsessed culture and the conveniences that fed it. In 1905, the Journal of the American Medical Association warned that “modern conveniences” added to daily stress and alienated people from others. Face-to-face conversations were being replaced by hurried telephone calls, the article suggested, and labor- saving technology was only making us more sedentary. These trends, according to the authors, contributed to high blood pressure, obesity and “nervous strain.”

One of the knocks against conveniences has always been that even as they promise to save us time and trouble, they always seem to make us busier. That was Betty Friedan’s argument in her 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, in which she showed that household conveniences only created more demands and greater expectations for women. “Even with all the new labor-saving appliances,” she wrote, “the modern American housewife probably spends more time on housework than her grandmother.”

A healthy suspicion of convenience doesn’t necessarily make you a drudge or a workaholic. I like avoiding work as much as anyone. But it is no accident that so many of the avocations that we see as self-defining — gardening, do-it-yourself home repair, music-making, to name a few examples — are inherently inefficient and also demand the most patience, effort and focus. They seem authentic and personal to us precisely because they ask so much of us. Idioms like “marriage of convenience,” on the other hand, communicate our disapproval of arrangements that seem merely shadily expedient.

Convenience has an illusory quality. We always seem to be getting closer to the ease we seek, but it somehow always escapes us. Thus one convenience begets another, and another. With convenience, as with potato chips, you can never be satisfied with a little bit. You always want more.

Of all the natural forces harnessed by modern industrialized humanity, cold gets too little attention.

Heat is easier to understand as a creative force — all that forging, welding, brewing and burning not only fueled the Industrial Revolution, it also fed our language: When we are repeatedly successful, we are on a hot streak; when approaching a truth, we are getting warm.

But ice, too, played its part in making the modern world. Ice was the center of a global trade in the 19th century that transformed domestic life. Its premise sounds comical — harvest ice in Massachusetts and ship it to Martinique and India and New Orleans. But the entrepreneur behind this unlikely business plan, a Bostonian named Frederic Tudor, briefly turned New England into the world’s ice machine and created an industry that sold and shipped thousands of tons of sawdust-packed ice to the world’s sweltering locations. One of the reason Tudor’s venture was successful was that he saw the importance of creating demand for a product that people had no idea they could not live without. He taught resort-hotel bartenders, for example, how to use ice to create cold mixed drinks. If you have ever listened to a hipster mixologist discourse at length about the advantages of his boutique ice cubes, you have Tudor to blame.

The ice business also led directly to the birth of the convenience store, the defining landscape artifact of 20th-century America. The first such store, the Southland Ice Company in Dallas, run by a man called Uncle Johnny, began selling milk, bread and other groceries to make up for seasonal slumps in ice sales. His innovation was so successful that his corporate bosses took notice. They applied the strategy in stores around the country, and in 1946 gave them the name 7-Eleven.

The ice fields at either end of the globe, hundreds of feet deep, hold traces of the atmosphere of thousands of years past. In this sense, ice is a container of time. Embedded in the ice of Greenland or McMurdo Sound are small bubbles, the visible traces of air trapped millennia ago. Antarctic ice preserves even the century-old remains of Scott and his expedition, found by search parties a year later and “buried” in the only way possible on the Ross Ice Shelf — in a cairn of heaped snow. Because the ice shelf is fed by glaciers and accumulates more ice on the surface even as its underside thaws and freezes again, that cairn is now believed to be encased in about 55 feet of ice. The frozen regions of the world can be read like a clock that give us a view into the past. Its melting glaciers and rising seas provide a look into our future, too.

What would Clarence Birdseye have made of some of the products now offered by the industry he helped found? Would he have been happy to shop for cheesesteak eggrolls in the freezer aisle of Trader Joe’s? Remember, this is a guy with the patience and the gustatory bravado to prize a good gull gravy. A guy willing to let his lynx marinate for a month to get it just right. He would not seem to have been a person to value convenience above all.

But his innovations did help to create a new industry, and that industry doomed the old Labrador fisheries that once sold salt cod to Europe and South America. The new post-Birdseye business model processed cod and other fish as frozen goods for consumers in the U.S., and it was such a success that the industry expanded too rapidly. Doing so, it quickly depleted stocks of fish in the seas off Labrador, and by the end of the 20th century, a halt had to be called to cod fishing.

The problem with arguing against convenience is that it puts you on the side of inconvenience. And no one wants to be there. We may talk a fine game about the need for patience and fortitude, but put us in a slow-moving line for anything, and we will whine and protest like 5-year-olds. My doubts about convenience are not based on any sense of moral superiority. The easy way has always been the way for me. But the truth is that not even the most dedicated slacker could really thrive in a life that included only ease and convenience. The psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, in his work on the positive state of engagement that he called “flow,” wrote that people fully realized themselves only when immersed in a task that challenged them just enough but not too much. There could be no flow, he suggested, without a certain amount of friction.

The promise of convenience is that it will save us time and smooth out the many small frictions that complicate our days. It will make things easier. But convenience for its own sake leaves us empty. There is no sense saving time if we don’t know what to do with the time we have saved. The seas off Labrador’s shores are warming at unprecedented rates, its winters have grown shorter by weeks, and its ice cover has shrunk by one-third compared to a decade ago. This has produced an unsurprising adaptation from the coastal Inuit communities who can no longer safely access traditional hunting and fishing areas because of thin ice. They now instead rely more on grocery stores to provide expensive, processed food. Because it is more convenient.

Andrew Santella is the author of Soon: An Overdue History of Procrastination, From Leonardo and Darwin to You and Me. He lives in Brooklyn, where he is greatly inconvenienced.