The June ceremony that marked the induction of Philip S. Gutierrez ‘81 to the federal bench in California’s central district was filled with a round of relaxed remembrance and storytelling by touchstone figures in his life.

There was the federal judge who had hired Philip’s mother, a divorced mother of four, to be his courtroom clerk and had known Philip as a youngster. There was an old law partner, now a judge, who, after noting what she called “a real spark in this man,” had encouraged him to become a judge. Then came others who hailed him for his penetrating legal mind, his devotion to his family and his work as chairman of the California Judges Association’s Committee on Judicial Ethics.

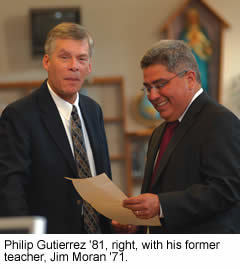

The most eloquent and elegant speaker had had nothing to do with the legal profession. He was Jim Moran ‘71. During their four years together at Cantwell High School in the 1970s, Moran had become Philip’s teacher of a lifetime.

Stepping to a podium at the front of the courtroom, Moran recalled a pattern of life at the Los Angeles high school, where Gutierrez was in his English classes for three years.

“Usually, the echoes of the dismissal bell hadn’t even subsided before he was in my room, standing politely for often an hour or more to the side of my desk—to badger, to listen, to argue, to persuade—to do all that was necessary to nurture a developing intellect of the range and depth that I know characterize him to this day,” Moran said.

Thirty years earlier Gutierrez had talked of Moran’s importance as he gave the salutatorian speech at the graduation of the Cantwell class of 1977. He talked of how Moran had enlarged the imaginations of young men who had grown up in the turbulent barrios of East Los Angeles, where gangs marked their territory in graffiti and blood.

“I sincerely love this man,‘’ Gutierrez said in that long ago speech. “He has been a father to me. But to all of us he has given dreams never known to us.” He went on to note the college destinations of some of his classmates, who at Moran’s urging had looked far beyond California schools and had won acceptance at Yale, Cornell, Penn and Notre Dame.

Turning toward his high school teacher, he said. “Mr. Moran, you’ve told us we can do it, and we will. But most importantly, you’ve told us never to stop living, never to get smothered into something unwanted.”

The day after his induction ceremony, Judge Gutierrez recalled Moran and Notre Dame during a conversation in his L.A. office, which looks out across Interstate 5, past historic Union Station and up to the San Gabriel Mountains.

On the shelves around him were photos of his wife, daughter and son, and books that included a biography of Earl Warren and Father Ted Hesburgh’s God, Country, Notre Dame. He pointed to a framed poster just given to him by his brother, urging him to “Judge Like a Champion Today.”

A world through books

He marveled at the effect that Moran’s English classes, with their heavy concentration on American writers, had on his world view. He fondly remembered Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage, Emerson’s The American Scholar.

“The way he taught them really had the effect of bringing the heartland of America into this Latino community,” Gutierrez said. “I think it made us want to buy into the idea of really being a part of this country, with an understanding of its traditions through its literature.”

He recalled Moran’s talent at making literary themes come alive with personal narratives. When teaching Red Badge for example, Moran would relate the stories of his own visits to Antietam and Gettysburg, the sites of battles whose heroes and turning points he recalled with a thrilling vividness and immediacy.

Those stories often took tangents that involved Moran’s days at Notre Dame. At Gettysburg, for example, there is a statue of Holy Cross Father William Corby blessing the troops. A replica of that statue on the Notre Dame campus is nicknamed “Fair Catch Corby.” That tangent took Moran to his encyclopedic knowledge of Notre Dame football, from Rockne through Parseghian.

And that took him to tales of life at Farley Hall, including the story of the Gerbil Circus. Moran tethered a friend’s pet gerbils to the plastic chariots of his 1959 Ben Hur toy set, threw a towel across his back as he declared himself the Caesar and improvised chariot races in Room 304 of Farley Hall.

“It was one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen,” recalled Farley dorm mate Jack Candon ‘72. Candon also recalled Moran’s penchant for cranking out 15-page papers—in a single draft hours before they were due—which inevitably received As from his admiring professors.

“Jim’s mind was always racing ahead of everyone else,” said Candon, who says that even today, after their occasional reunions, his wife says in awe: “Imagine having Jim Moran for a teacher!”

The young Gutierrez was enthralled by Moran’s stories, by their sense of the possibility of physical and moral adventure, of fellowship at a campus in faraway Indiana.

“What most impressed me was that he became so close to the people there,” he said. “I wanted to have that experience. That’s why I went to Notre Dame.”

So Gutierrez turned down Stanford and Yale and headed to South Bend. Moran was thrilled. As he recalled at the induction ceremony, “I felt that sending this dynamo of energy and questions into the heart of a bastion of white, traditional Middle American Catholicism would be good for both him and the institution.”

There, after struggling through his first winter, Gutierrez also became attached to the place. He majored in English and spent his sophomore year in Ireland, an experience whose joy is reflected in the names of his children, Connor, 13, and Erin, 10.

Then it was off to UCLA law school, private practice, elevation to managing partner and his 1997 appointment to the state bench by Governor Pete Wilson. Late last year, Gutierrez, a Republican, was nominated to the federal bench by President Bush; early this year he received Senate approval.

Possibilities

Gutierrez has long sought to enlarge the sense of possibility among young Latinos, many of them immigrants or children of immigrants, who fill the schools of Southern California. He has addressed school assemblies, sometimes with Cantwell classmate Joe Cepeda, a gifted artist who has achieved success as the illustrator of children’s books.

Cepeda was also touched by Moran. As graduation approached in 1977, he wrote in Moran’s copy of the yearbook: “All those stories, talks and bits of advice have been something that have settled in my mind as to create dreams. That part of you will be with me.”

From his Whittier, California, studio, Cepeda said of Moran, who continues to teach, both at Mayfield Senior School in Pasadena and East Los Angeles College: “I’ve been to a lot of schools, and what I find is that it usually comes down to people who have a special gift. In the middle of what can be perceived as a blight, with a lot of closed doors, there are people out there who can inspire. Jim is one of those people.”

At the Gutierrez induction ceremony, Moran had brought the story full circle, invoking the last poem he taught to each of his honors English classes. Written by Stephen Spender, it urged emulation of “those who in their lives fought for life,/Who wore at their hearts the fire’s center./Born of the sun, they traveled a short while towards the sun,/And left the vivid air signed with their honor.”

Then he concluded by expressing confidence that Judge Gutierrez would carry on in that tradition. He turned, bowed slightly and said, “Congratulations, your honor.”

The audience, after a moment of awed silence, broke into loud and prolonged applause for the teacher and the judge who had been his student.

Jerry Kammer, a Notre Dame classmate of Jim Moran’s, is a Washington correspondent for the Copley News Service.