Editor’s Note: On a peaceful Saturday morning in early September I sat in my backyard, savoring the scene before me: the grass and trees and black-eyed Susans, all feeling different now — as the sunlight and scents took on an autumn mood. It reminded me of a memorable essay from years back, and that got me to conjuring a list of all-time personal favorites published in the magazine over the years. I decided to share them with you, a new one each Saturday morning until the calendar reaches 2024. I did not go deep into the past to pull out this tale told by an inmate enrolled in the Moreau College Initiative at the Westville Correctional Facility. It's a remarkable narrative of intellect, insight and perseverance so compelling that it is not just a favorite of mine but was cited by the editor of the year's Best American Essays. —Kerry Temple ’74

In class we learned that John Milton hid the acrostic SATAN in his epic poem Paradise Lost. The poem recounts a heavenly battle between angels that results in the fall of man when the defeated Satan convinces Eve to eat from the forbidden tree. After class, I went straight back to the dorm and sat next to my bed. I intended to search the work for other acrostics — letters across lines of the poem that spell out a word or a phrase. With a ruler in one hand and Paradise Lost in the other, I dove in. I was dumbstruck when, 38 lines in, I discovered the acrostic THOTH alongside the first mention of Satan. I dropped the ruler and leaned back against my bunk in disbelief. Could it really be that easy? Scholars have been studying this poem for 350 years. Did I just discover something?

The officer yelled, “Chow, going out!” I was bewildered. The commotion of voices slowly funneled off the dorm as I struggled to regain my balance. The Son of God was meant to incarnate as Jesus. . . . Did Milton use an acrostic to reveal Satan’s incarnation as an Egyptian god?

My first semester with the Moreau College Initiative (MCI) was in the fall of 2017. MCI is a joint effort between Holy Cross College and the University of Notre Dame to offer degree programs to prisoners incarcerated at Westville Correctional Facility, an Indiana state prison for men. That summer, after my transfer to Westville, I had answered a call to apply for the program, one of many hopeful candidates sitting down in a crowded room to write an application essay. My submission got me to the second round. I then had to be interviewed by two professors before earning the opportunity. I almost jumped with joy when I was accepted. Only 25 of about 200 applicants made it.

Soon I was pursuing an associate degree in liberal arts. The workload worried me. MCI provides real professors and in-class experiences. Some professors drive more than 40 miles from South Bend to Westville for each class. And, although I am street smart, I lacked a lot of formal education. I had hardly made it into high school before my arrest at age 15 for robbing and pistol-whipping an acquaintance during a drug deal, and for an unrelated burglary. I earned my GED in a maximum security state prison. Then I simply read everything I could get my hands on while confined to a cell. I made it a principle to finish every book I started, and I turned every unfamiliar word I came across into a flashcard — including “Thoth,” which I found in a poem by Oscar Wilde. I was adequate in English, but the academic world presented new challenges. MCI was the big leagues, and the rules were all different. I didn’t know how to speak, how to write, how to be effective. I was a novice. But I had come a long way.

My first night in prison, in January 2010, felt like a graveyard. I was 16, lost to myself and the world. My guiding light came from a dream I’d had while still in county jail: A faceless figure showed me a long, meandering road and said, “If you do nothing, you become nothing.” It pushed me forward, but I was bound up in bad habits and had long been hiding my errancy. Before my arrest, sin had grown through my heart and head like weeds until it so thoroughly pervaded my identity that where I landed after my crimes reflected what I had already become: a prisoner. My lies had distorted my will so completely that disease was inevitable. Now, like a cancer patient taking radiation, I sacrificed the good of my being in hopes of eradicating the bad. I lived in anguish. Solitude was the best society for such a severance, for the tears of my shame were seen by none but God.

Reading Shakespeare was torturous. I couldn’t comprehend how anyone in their right mind would willingly subject themselves to Elizabethan English. I was learning a language I would never speak, though at one point I thought I might start dreaming in it.

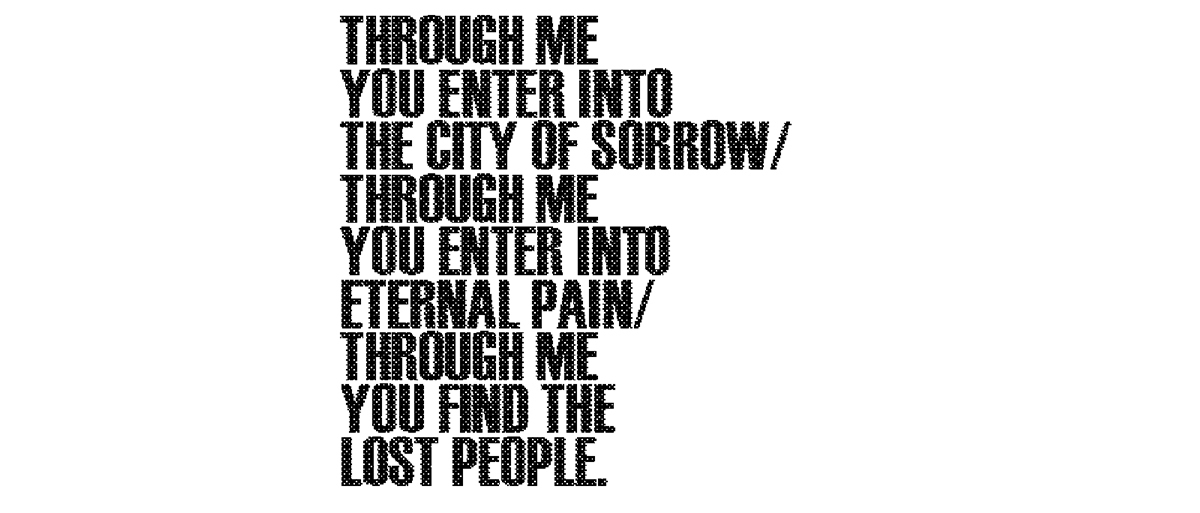

Working backwards, I got to the root of my words and actions, seeking out the causes of all effects. I was meticulous. Those knots that I couldn’t untie I slashed to pieces. I had faith that if I tried hard enough and persisted long enough, I would find order in my disorder. I stopped leaving my cell. In 4-inch high Italian, I inscribed the words of Dante on the inside of my cell door: Through me you enter into the city of sorrow / Through me you enter into eternal pain / Through me you find the lost people. The door, which led to the dayroom of that prison, transformed into hell’s gate, and I resisted walking through it. I turned my sight inward and sought to illuminate every cave, den and shade of death inside me; I left no rock unturned. Year after year after year, I fought to make good of evil. I slowly discovered the pattern of chaos and released myself from its bonds. The desire to become something, and the fear of being nothing, propelled me.

My first week of college was nerve-wracking. It felt like walking into high school all over again. People you see only in passing are now sitting next to you in class. You have to figure out where your classrooms are and get a feel for the professors. Everyone has new books, new folders, a full pen. Syllabi are passed around and the notetaking begins. It is thrilling and scary. As your stack of books grows, you wonder whether it wasn’t all a mistake and if you can hack it. In the middle of class you look up and realize, Hey, I’m a college student now. And a big smile stretches across your soul. That is, until you sit down in a class that threatens to overwhelm you.

The following spring I took my first 300-level course, English 327: Shakespeare’s Plays and Milton’s Paradise Lost. It checked my elation. The professor, Stephen Fallon, is an authority on John Milton. Seeing a once in a lifetime opportunity, I enrolled to challenge myself. He set the tone for the semester on day one, exuding experience and knowledge. He expected rigorous reading and discussion.

The class met once a week in an area of the prison set aside for the college. Without exception, I had to be on time to class, which meant being controlled and supervised at all times. Any deviation from such rules could result in disciplinary actions — being late is called a “Refusal,” and I could lose the ability to make phone calls for a week, use the prison email system or order commissary. It is important to me that I not take such a chance.

At Westville, breakfast is served at 4:30 a.m. People pull themselves out of bed to go eat. I usually sleep through it. Running down to a crowded dining hall before dawn gets old. When most people go back to bed after returning from breakfast, I get up. I order my own food from commissary so breakfast is peaceful. I make a bowl of cereal, drink a cup of coffee and ease into the day. Sitting next to my bunk, I look out across the open dorm filled with sleeping men nestled in their blankets. School doesn’t start until 8, so I have time to think while everyone is quiet.

Once a professor arrives, the dorm officer gets a phone call from the school. She yells the class name. “English! With Dr. Fallon!” The students line up at the door. Sometimes the professors are early, and sometimes they are late. A lot depends on how expedient the search process is when they come through the front gate. The way things operate seems to change by the day. Prison is a microcosm of life; inhabitants become especially dependent on time. Being early or late disrupts an internal order we all carry. The atmosphere is so authoritarian that one grows fearful of missing a callout, then anxious at its uneventful passing: “Did they call out class? Did they leave already? What class went out?”

When I near the dormitory door I pray there hasn’t been an error in the custody officers’ prisoner movement sheets that would prevent me from going to class; sometimes information is missing or incorrect. It creates havoc. If you don’t know you’ve been added somewhere or dropped off, the line of questioning put to you by an officer when you are found “out of place” is hard. Most days pass without any disruption, but the possibility sparks anxiety.

I depart the sanctuary of the dorm to get to the safe haven of a classroom. As I jog down the stairs and out of the building, I keep my head on a swivel. I’m housed in the worst part of the prison, the disciplinary side where people are usually moved for getting in trouble. Paranoia is a legit protection. The college dorm is here because this side of the prison has the space to house the school. The distance in between the dorm and the classrooms, although no more than a couple hundred feet, holds the awful unknown. I walk through a prison yard penned in by buildings that form a pentagon. Twelve-foot fences topped with barbed wire border the sidewalks.

Getting to class through the formal checkpoints and informal stop-checks emotionally unscathed is difficult. When I approach these checkpoints, my whistling chokes down to a hum, and then the hum dies to angst. Sometimes the mere presence of an officer is enough to throw off my melody — I never know if I will be stopped and ordered up against the wall for a frisk. Even though I never provide a reason to be stopped, I’m always fearful of these encounters. A good day sees me get to school with the class topic still on my mind.

When I reach the classrooms, I check in with an officer then go about my business. The school comprises two individual libraries — fiction and nonfiction — one computer lab and four classrooms. Classes last up to three hours and meet once a week. Study halls offer the only access to a computer. The lab is strictly a place to type papers. No internet. Limited features. No printer. And all papers are sent back to the college through the director’s flash drive.

I sign up for as many study halls as I can. They keep me off the dorm. And although I’ve handwritten my fair share of prison letters, a handwritten academic paper always seems lousy compared to its typed version.

After the morning session, classes dismiss for lunch. We walk back to the dorm debating contested points. We have 30 minutes to scarf down food while preparing to return. The time burns like a wick. Before I know it, I’m headed back with a different set of books. Monday through Friday, the only thing that changes is the class.

The first day of Dr. Fallon’s course left me sick. In the pit of my stomach, I felt like I’d made a mistake. There I sat before the most educated man I’d ever met in awe and envy. The moment was overwhelming. I didn’t know what to expect. I knew so little that dropping the course wasn’t an option. I’d never heard of such a thing, so I couldn’t have run even if I wanted to. Instead I hung on.

The class was split in half: two months for Shakespeare and two for Milton. Reading Shakespeare was torturous. I couldn’t comprehend how anyone in their right mind would willingly subject themselves to Elizabethan English. I was learning a language I would never speak, though at one point I thought I might start dreaming in it. Hamlet, King Lear and The Winter’s Tale were assigned. I am no stranger to reading, but this was another level. I had to pick these works apart thematically. I relied on the class discussions. Bouncing ideas off of other students became an essential source of inspiration and enlightenment.

I gained confidence, but despite my tenacity, it didn’t take long for the old uncertainty to reappear. Halfway through the semester I realized I didn’t know how to write an academic paper. The first critique shocked my ego; what I thought I knew was trash. The professor didn’t say as much, but I read through the formality. I had summarized too much. My sentences were too lengthy. My paragraphs were choked with ideas. Awkward. Wordy. The thought sat on my mind: I was failing to meet my own expectations.

Milton was no easier, though I was learning to glean more from the passages by slowing my reading. The years I’d spent on self-analysis had left me with a robust capacity to think critically. Dr. Fallon taught me how to repurpose it. He sparked my real appreciation for the work and revealed meanings within the texts that astounded me. Paradise Lost has layers, and he taught me to see beneath the surface.

I spent all of Tuesday and half of Wednesday rewriting my paper. I dressed in thermals, sweats, fleece shorts, a khaki jumpsuit, a Department of Corrections winter jacket, a sock hat and fleece gloves. I drank hot water. It took all this just to make sitting in the dayroom bearable.

In our second-to-last class, we discussed an acrostic Milton had implanted in his poem. A footnote in Book 9 of our edition pointed to the SATAN acrostic discovered by a Milton scholar. We all assumed that if there were others they would have been noted, too, so we were surprised when a student pointed out the acrostic SLOW in lines 643 to 646.

Now I was conscious of the Miltonic acrostics. I made my first discovery in that same class, as we approached the point in the poem where Adam must choose whether to follow Eve. She has eaten from the tree of knowledge of good and evil. Just before he decides, starting in line 911, an acrostic appears: SAW THE BONE. It warns Adam to separate himself from Eve before it is too late. God had created Eve from Adam’s rib. In the line following this acrostic, Adam decides to fall with Eve — the flesh of his flesh and bone of his bone.

Dr. Fallon’s face lit up when I pointed this out. Sure, SLOW was notable, but this, at such a critical juncture in the poem, well, this was veritable gold. Now that I was aware, the acrostics stood out to me like Christmas lights in July, and I realized I possessed an advantage. The decade I’d spent in confinement, pulling order from disorder, making sense of the senselessness, had conditioned me.

I was swimming in acrostics by the next afternoon. Almost 60 in total. Without internet access, I didn’t know how many were new discoveries. I found more with each search. I tried to share my excitement with neighbors, but that elicited only strange looks and conspiracy-theory remarks. Quietly and contentedly, I kept my own counsel. Finally the nervousness surrounding the originality of my discoveries got the best of me. I made a couple of collect calls. I asked my friends to Google “Milton acrostics.” Although I lost claim to most of the minor discoveries like LOST, BOAT and DOG, my major findings were new. My mind raced at light speed. From the receiver I heard, “Miles . . . are you still there?” My thesis and argument were already taking shape in my head.

That next week was finals. Searching the text so thoroughly for acrostics would help me survive the exam. I knew the book from front to back. So I split my study time between writing my final paper and crafting an extra one on Miltonic acrostics. On the exam day, I raced through the test, hoping to get a private moment with Dr. Fallon before class ended. I had one chance to discuss my findings. I wasn’t going to miss it.

With so little time, I’m sure I sounded insane putting forth such a momentous claim on one of literature’s most studied texts. I felt like a madman. Understandably, my claim to have found Satan’s incarnation as the Egyptian god Thoth was met with an encouraging skepticism. I could see that I needed a better argument. I asked, “If I write the paper, will you help me?” Dr. Fallon cheerfully agreed. He did what any scholar would do: He sent me away with some big questions and the understanding that I must support my claims. I left that day on high, but I soon hit an impasse. MCI lacked a research assistant that summer semester, and Notre Dame’s library is closed to requests from MCI students between terms. I had to wait for the fall.

I turned through my thoughts all summer. The heat was unbearable. The college dorm needed repair, so we were moved into an empty cell house. It was nice to have a room, but with no door, no air conditioning, bad ventilation and a bricked-up window to boot, life was tough. I lay on my bunk nearly nude, earplugs in, eyes closed, and I thought. The story unfolded before me like sheet music. The more I thought about it, the clearer it became. I just needed to find my support.

When the fall semester began, I rushed to begin. I skimmed the “works cited” sections of two Paradise Lost editions and chose sources I suspected would be helpful. Articles and books poured in. The more I read, the surer I became. I wrote by day and read by night. “Lights out” was at 11 p.m., so I read in the dark. I chewed through material, my notebook slowly filling. I took a break only when my eyes tired; even then, I’d just stare at the walls and envision the end result. A familiar feeling of being trapped propelled me.

After four months of research and writing, I sent Dr. Fallon a 33-page rough draft. I had grown too familiar with my own work to be productive. I nitpicked issues that weren’t issues at all. I grew weary of my arguments and wary of my thesis. It was time to let other eyes scrutinize it. With winter break looming, I wouldn’t get a response for a while. I tried to stop thinking about it.

By the start of the spring semester I had my answer. I’d gone on a couple of tangents and was a bit wordy in spots, but the evidence was there. Dr. Fallon suggested I clean up the paper and submit a truncated version to the Journal of Undergraduate Research at Notre Dame. I was ecstatic. However, I checked myself: A tremendous amount of editing still needed to be done. With five courses on my plate in the new semester, I let the paper sit.

It wasn’t until one of the MCI professors asked one Monday if my revisions were almost complete that I took alarm; I was unaware of the deadline that Friday. My stomach did a backflip. I was horrified to think I was about to miss my shot after working so hard. I hadn’t edited a single sentence, but I refused to fail. I devoted my study halls to the work. Only a force of nature could’ve deterred my will.

Then came the news: Polar vortex grips the nation, projecting record lows.

The prison locked down from Tuesday through Thursday: no school, no study hall. I was cut off from the computer — and my paper. It felt like I couldn’t catch a break. My only choice was to rewrite the paper by hand from a draft I had printed the semester before. Then, come Friday, I’d have to find a way to type it.

The polar vortex was no joke. With the wind chill, the temperature early Tuesday morning dropped to almost 50 below zero. It was hardly above freezing inside. The cell house’s dayroom is flanked by two long hallways with cells on either side. At the end of each hallway is a wall heater the size of a microwave. They were no match for the extreme cold.

I spent all of Tuesday and half of Wednesday rewriting my paper. I dressed in thermals, sweats, fleece shorts, a khaki jumpsuit, a Department of Corrections winter jacket, a sock hat and fleece gloves. I drank hot water. It took all this just to make sitting in the dayroom bearable. I wrote each paragraph on its own sheet of paper in pencil so I could work systematically. On Wednesday afternoon, I began editing. By this time, my hand was killing me. Having no time to stop, I removed my glove and let the air cool my aching hand.

By Thursday night I was frayed. I’d cut the paper down from 33 pages to 19. I rolled every sentence around in my mouth like a jawbreaker, testing its strength. Having to rework them by hand turned out to be an advantage. I accomplished the task in a much more detailed and careful manner than I would have had I used a computer. I achieved a clarity that revealed a better argument than I’d known was there: Through the acrostics, Milton links Satan to Thoth, Hermes, Mercury, Odin — he’s both the pervasive pagan evil and the ultimate epic hero, weaving himself into the legends of every culture. My paper was clear, concise and controlled. Only one complication remained: How on earth would I type it in time?

My Friday was booked. I had classes from 8 a.m. until 2:30 p.m. I wanted to pull my hair out. I thought about explaining myself to my professors and asking leave for the day. But what would I say? Hey, I need to ditch your class to type this article I hope to get published. What if they said no? What if they asked the officer and he said no simply because he didn’t want to make the call? I decided it was better to ask forgiveness than permission. For the first — and only — time in my college career, I skipped class. No one asked any questions. I slipped into the computer lab and went to work.

Within an hour that morning I knew I would need the afternoon as well. That meant I’d have to ditch Constitutional Law. And boy did I enjoy that class; I had even spent the night before preparing. Luckily, it was the professors who canceled; they were coming from the University of Chicago and the roads were still bad. It felt like a gift. I typed with all deliberate speed, without a second to spare. I finished at 2:31 p.m. The director immediately downloaded the paper onto her flash drive. I hadn’t even proofread it. It felt like I’d run a marathon. Mentally, I was doubled over in the heat of the finish.

Then came the wait to see if I’d be published. Once again I tried to put it out of my mind.

Ten weeks passed.

On Monday, April 8, 2019, I got a letter from the editor — I was in! The first word I saw was “Congratulations!” It continued, “After substantial review and deliberation, we have selected Miles’ paper, “‘Metacommentary in Milton’s Paradise Lost.’”

I couldn’t believe it. I walked back to class in disbelief. I caught many quizzical looks as people wondered how microeconomics could excite me so much. The rest of my professor’s lecture went out the window. Suddenly I remembered what it meant to be so happy that focusing on anything else was an impossibility.

For 10 years, I had struggled against my lesser nature. Once a high school dropout, I’d become by turns a youth incarcerated as an adult, a felon with an almost 40-year sentence, a college student published in a prestigious journal. I’d begun in the darkness of sin and fought my way into the light of grace. I withstood the sorrow of solitude by believing that my hermetic education would one day free me from my prison. Overcoming all the barriers and obstacles was an epic struggle, but I hadn’t shied away from the challenge. I finally felt like something more than a prisoner. And who I am is still nothing . . . compared to who I will become.

Miles Folsom completed his associate degree in December 2019 and is now working toward his bachelor’s degree through the Moreau College Initiative. He hopes to attend graduate school after his release from prison and to build “the most humane prison in the world,” a project he’s been designing for the last six years.