On February 5, I flew to Pennsylvania to see my father, who was hospitalized after falling a few days earlier. Because of COVID-19 restrictions, I was not allowed to visit him in the hospital. For three days, I begged and begged, but could not see him. I called many times and talked with the nurse in charge. No luck.

On February 8, I went to the hospital again. No one was at the front desk, so I just slipped by, took the elevator to the third floor and went to see Dad. I was so happy to see him and spent about three hours with him. I took a selfie of us and sent it to my brother and sister. My brother, who lives nearby, also came to the hospital. When he got there, no one was sitting at the front desk, so he came up to Dad’s room.

After my brother left, a nurse charged into the room and scolded me for being in the hospital. At one point she said, “You were told twice that you are not allowed in the hospital.” I corrected her and said, “That is not true. I was told five times that I was not allowed in the hospital.” She didn’t laugh. It’s so sad when people don’t know how funny I am.

Since it was clear that I was not going to get back into that hospital, I returned to Notre Dame on February 9. A few days later, I learned that the hospital was now open to visitors, so on February 17, I flew home and went directly to see my father. February 17 was Ash Wednesday, the beginning of a Lent I never could have imagined.

My brother and I met with the hospital’s palliative care team. They told us that Dad was classified as “failure to thrive.” He had not taken in more than 200 calories a day for three weeks and his organs were shutting down. He probably had only seven to 10 days left, so they were recommending hospice care.

Since Dad’s admission to the hospital, we were planning for him to go to Holy Family Manor, a Catholic nursing home run by the Diocese of Allentown. It has an outstanding rehabilitation program.

I asked him, “Dad, do you want to go to Holy Family Manor for rehab, or do you want to go back to your apartment?” He looked at me and, like a child, he said, “To my apartment, Son. I’m comfortable there.” Even as I write these words months later, I cry when I hear him say, “To my apartment, Son. I’m comfortable there.”

St. Luke’s Hospice mobilized everything — hospital bed, bedside tray, nurse, medicine, oxygen tank — for Dad to return home on February 20.

I notified his siblings, nieces and nephews of the short time he had left and, the next day, Dad had 20 visitors. It was abundantly clear the role that friends and family and visitors play in a person’s healing. He also began to eat. After a few more days with visits from family and friends, he began to eat more and more. Those seven to 10 days extended to 47 days that I will treasure for eternity.

Dad had visitors every day. Friends he worked with 30 years ago, golfing buddies, his siblings, nieces and nephews, neighbors. Until the last week of his life, Dad interacted with everyone who visited. And everyone who came brought him food — homemade gnocchi, grapes, chicken cutlets, Italian wedding soup, lasagna. This explains why I gained 13 pounds during the days I was with him.

My brother, Jim, and his wife, Kathy, stopped by every day. Jim brought Italian ice many days. Dad loved the red ice and ate it readily. My sister, Mary Grace, and her husband, Bruce, came from South Bend three times, each time for a week, during those 47 days. My dad was always so happy to see his children.

“Son, are Nonnie and Grandpop dead?”

During those 47 days, Dad asked me that question about his parents countless times.

“Yes, Dad.”

Then he would say the dates of their deaths: “Grandpop, February 23, 1968, and Nonnie, December 2, 1990.”

He would look at me with a question mark on his face and ask, “Well, if they are dead why do I keep seeing them with me?” He would explain that they were on the front porch of their home, and he was at the bottom of the stairs. “They look at me and I look at them. And though we do not talk with each other, they are always so happy to see me. They smile at me.

“If they know that I am sick, why don’t they stop by my apartment to see me?”

One time I woke him up to give him medicine.

“Son, how did you find me here?”

“Where are you, Dad?”

“I’m here with your Mom and with Tom and Evelyn and Bobby and Anne.” These five people are dead. Tom, Evelyn, Bobby and Anne were lifelong friends. “We’re having such a good time talking and visiting. Why did you wake me up?”

Was Dad going between two worlds? Did the veil that separates life from death start to be lifted? Was it the medicine? Was it the end of life? Was it a combination of all three? I don’t know and might never know. All I do know is that it was very real. And I believe that Dad was going between life and death, that the veil that separates life from death was being lifted.

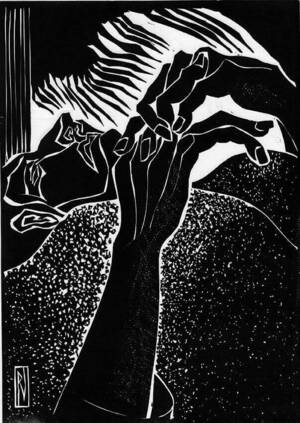

I sat in the chair next to Dad’s bed for hours on end. He mostly slept, and I sat there. Sometimes I prayed. Sometimes I opened my laptop and read my students’ essays. But more than anything, I held my father’s hand.

We “shook” hands, so to speak. Dad had a strong, firm grip until the very end. I loved holding and shaking his hand. With my thumb I would rub the back of his hand. I hope that it was as comforting to him as it was to me.

He would often say, “Son, get me up.”

So I would put the railing down on the side of the hospital bed that hospice provided, scoop him up into my arms and turn him so his legs dangled over the bed. He would usually say nothing, but I could see that he was trying to push up on his legs. He could not do it. He would just stare out into space. I would sit next to him and put my arm around him. Or I would massage his back.

Sometimes he would say, “Get me my walker.”

“But Dad, you are not able to walk.”

“Yes I am. Get me the walker.”

Back and forth until one of us gave in. If I gave him the walker, he soon realized he couldn’t stand up.

Then he would say, “I want to go back to bed.” I would scoop him up in my arms, swing him around, put up the railing and then boost him up in the bed.

One night we did the “sit me up, Son” routine 14 times, almost consecutively. I don’t know if he didn’t remember that we had just done it or what. That night I said to him, “But Dad, we’ve already done this 14 times,” to which he responded, “Well, then, what’s 15?” How could I not love him? How much he wanted to walk again.

Sometimes while sitting on the edge of the bed, he would say, “Stand me up, Son.” I would get him in a bear hug and he would hold me, and I would stand him up. But after a few seconds, he would start to yell that I was going to drop him and he was going to fall. I assured him I would not let him fall, and then I would sit him back down on the edge of the bed.

Almost like clockwork, around 5:30 p.m., Dad would go from congenial and kind to angry and disagreeable. He would fight about anything. He would not want to take his medicine. He would yell and scream and make all sorts of unreasonable demands. He wanted this. No, he didn’t. He wanted that. No, not that.

We often argued. Then I would feel terrible and apologize. And he would say, “Well, Son, we’re like two old Italian men. We fight and fight, and it will make us stronger.”

After several evenings like this, I told the hospice nurse. She said some patients change personalities around sunset. They call them “sundowners.” She assured me that my father most likely did not remember the arguing the next morning. And he certainly never acted like he did, but I have to admit that I was at my wit’s end several times.

Eventually I was able to give him an anti-anxiety drug called Haldol that would calm him. How I hated to give him that medicine. I always felt like the guy at the zoo with a stun gun trying to soothe the lion.

Haldol would make him a bit loopy. Within 20 minutes of a dose, he would say, “Son, there’s something not right with my head. It feels weird.” I would often go to another room and cry. The medicine would also make him groggy, and I would feel bad about welcoming his grogginess so I could get some sleep. Without the medicine, he would be uncomfortable, constantly moving, anxious. With it, he would be calm and restful. On one level, Haldol obviously made life easier on me, the caregiver. At the same time, I hated, hated, hated giving him that drug.

Even though his health was declining, he became more human.

One night I decided not to give it to him. Mistake. He had a fitful night, throwing the pillows — all six of them — out of the bed, and the covers and the pad out from under him onto the floor. He kept trying to climb out of bed, throwing his legs over the railing. I saw firsthand what it was like when he did not have Haldol.

I also had to give him oxycodone, an opioid, to help with his pain. When he would cry out, I would ask him, “Dad, what hurts?” He would always say, “Me.”

My head understands that I had to give Dad those drugs. My heart is still torn. I will probably go to my grave wondering if I hastened his death by giving him Haldol and oxycodone. Whenever I mention this, people say, “Would you have wanted him to have a terrible and painful death?” Of course not. But when you are the one giving the medicine, it’s hard to be at peace.

It was not always so difficult. He mixed up his days and nights, often waking at odd hours, and we would have late-night conversations. Those talks were one of the graces of spending Dad’s final weeks with him.

His most common theme was gratitude. Gratitude for all that God had given him, for his family, for his friends, for his work.

He became more and more transparent as the end drew closer. There was nothing to hide — not that I learned any dark secret from his life. Rather, he was more comfortable being himself, the person who God created him to be. Even though his health was declining, he became more human.

On Easter Tuesday, April 6, I celebrated Mass using the table next to Dad’s bed. Two of my cousins, Patty Ann and Mitz, had stopped by, so we all celebrated Mass together. Dad had already been asleep since Easter Sunday, not awakening at all.

During the Mass, however, when I prayed the words of consecration — “This is my Body” — over the bread, Dad moved his hands from his sides, put them on his chest and folded them in prayer. I had not noticed, but Patty and Mitz pointed it out.

On Easter Thursday I decided to celebrate Mass early in the day. Dad had not been able to swallow for several days, so I could not give him Holy Communion. I had the idea to put a bit of the Precious Blood in a syringe and offer it to Dad sublingually. That was around 10 a.m.

About an hour later, his breathing became slower. I went to the kitchen and told my sister and brother, “Dad is about to die.” All of us surrounded his bed, and at 11:17 a.m. he took his last breath.

I was so grateful that the last thing he had taken was the Blood of Christ. Thanks be to God for this gift and for somehow inspiring me to celebrate Mass early that day.

Since the Church understands Easter Sunday until the following Sunday as one day, we can say that our father died on Easter Day. What a beautiful day to die.

May his soul rest in peace.

Father Joe Corpora works in Campus Ministry and the Alliance for Catholic Education. He is priest-in-residence at Dillon Hall and is one of 700 priests whom Pope Francis appointed in 2016 to serve as Missionaries of Mercy. His most recent book about this latter experience is Doing Mercy: A Path to Contemplation.