The guy in the spiky wig answers to the name Frank. Depending on the situation, that could refer to Detroit juvenile court judge Frank Szymanski ’74 or to Franklin Sane, lead singer of a tribute band that plays homage to the Psychedelic Furs and David Bowie.

Tonight he’s got a show — hence the early-MTV hairpiece — so it’s Mr. Sane, I presume. Either way, Frank suffices. Szymanski’s not particular, and both identities represent essential aspects of an indivisible self.

Interrupted on the way to set up onstage, Szymanski doubles back to introduce two band members at the bar finishing dinner. That abrupt shift itself is characteristic of the man: Whether out of curiosity, uncertainty or necessity, he’s tried on numerous identities, changes of direction in a life that he relates in his inimitable, winding way. Friends have learned to serve as “bookmarks,” holding a place in whatever story Szymanski’s telling to remind him, when he returns from a narrative detour, where he was headed in the first place.

His discoveries about himself along the way have coalesced into insights he dispenses in presentations and a book, Identity Design, intended to help people figure themselves out. Unhappiness, he says, doesn’t come from not having what you want, “it’s because you don’t know who you are.”

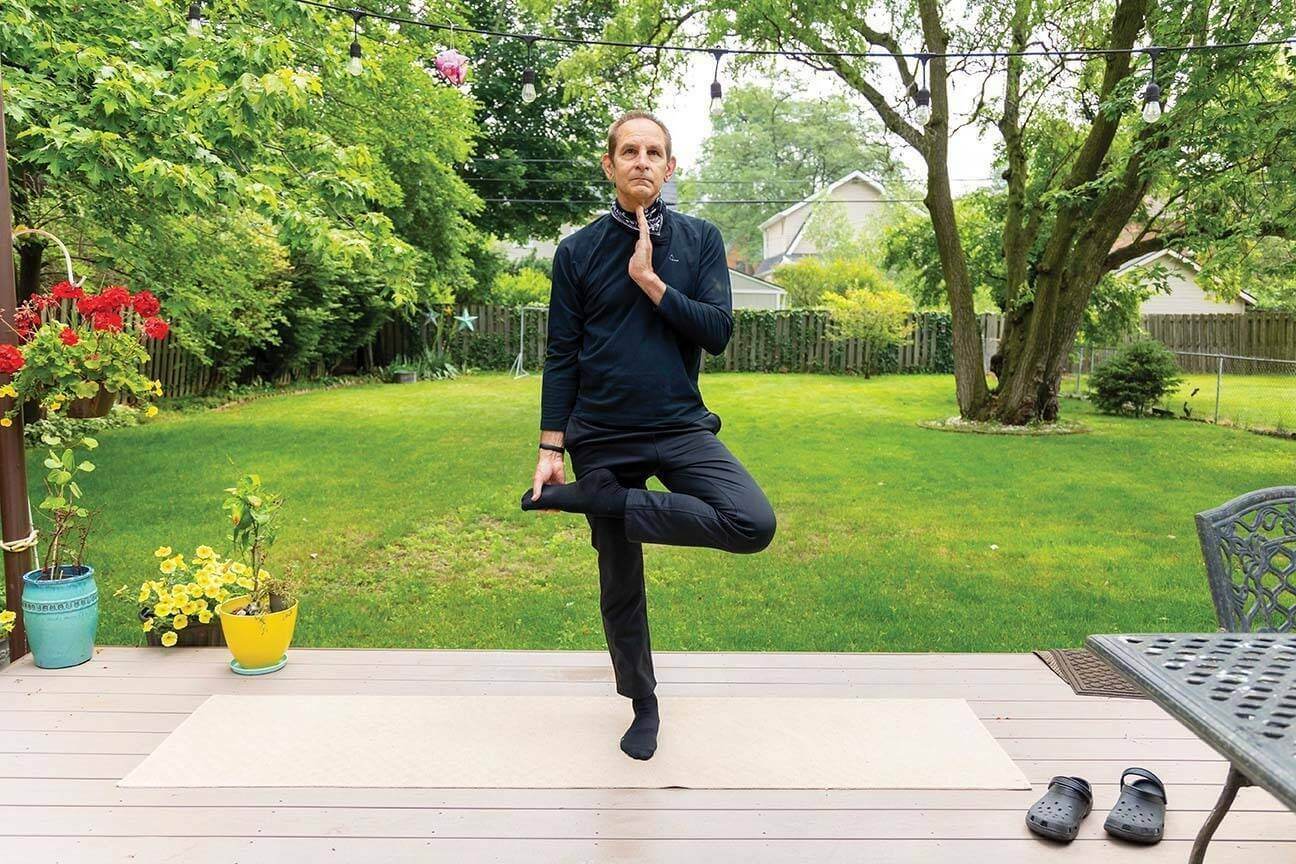

At first glance, Szymanski encompasses multiple identities not obviously connected to one another. There’s the big-hearted judge and the big-haired rocker, the purveyor of self-help wisdom and the performer of ’80s new-wave throwback music, the hockey player who grew up scrapping with five rambunctious brothers and the meditative yogi seeking peace within.

Where were we? Right. Back at the bar, meeting some of the band, which is, in fact, two bands, The Cinematic Furs and Ziggy Moondust & The Spiders from Mars. Over the years, Franklin Sane has led various ensembles on the mic, playing with numerous musicians who have come and gone.

In tonight’s lineup, guitarist Dave Landry has been jamming with the judge for more than four decades, dating back to the first stirrings of Szymanski’s glam-rock alter ego in law school.

“I like to call it ‘art school’ because it sounds cooler,” Szymanski says. “Because all the cool musicians come from art school, right? And the law’s an art, so,” — he roundabouts into the British accent of his stage persona — “we’re going to give me poetic license.”

No recordings survive from those “art school” days, he’s pleased to say. He had no previous training and didn’t then play an instrument. Always envisioning himself as a lead singer, he brought a frontman’s energy, if little else, to their idle noodling.

“I had the attitude — I always had the attitude,” he says. “The only thing I lacked was talent.”

Franklin Sane’s true origin story came a couple years after law school when life dealt Szymanski a combination of stinging blows — a bad breakup, an injury that meant no hockey, a legal career adrift. Ordinary problems, to be sure, especially when considered from his perch today as a judge encountering young people under relentless assault from but-for-the-grace-of-God circumstances.

Helping those kids, not just sentencing them from on high, has become a central focus of Szymanski’s life. He’s working to resuscitate a powerful Youth Deterrent Program in Detroit that the COVID-19 pandemic hampered. Adult inmates serving life sentences offer young people the benefit of their hard-won wisdom. They speak of regrets, of life lessons they’ll never have the chance to apply, but not in the “scared straight” tradition of instilling fear of consequences.

“Our children don’t need no one threatening them, cussing them out. They need more love in their life,” Darryl Woods says in a video about the program. He was an inmate at the time, serving a life sentence for murder before his 2019 release after nearly 30 years in prison. While locked up he became an ordained minister and now works with numerous groups to help young people avoid his fate and reduce recidivism among parolees.

James Hill-El, another since-paroled inmate featured in the video, expected to die in prison. He had served a decade for manslaughter and concealed weapon convictions before receiving a 50-year sentence in 1988 for cocaine and weapons possession. Like the other prisoners involved, he felt the rewards of the deterrent program deep in his own heart, his cautionary experience and caregiving example benefiting society far beyond the debt paid in time and confinement.

“This is probably the most fulfilling thing that I’ve done,” says Hill-El, who was released in March 2023. “You reach a certain part of your own humanity while you’re trying to give yourself.”

A serpentine personal journey, though more comfortable and sheltered than those of the men in the Youth Deterrent Program, has shown Szymanski the wisdom in that insight.

In the early 1980s, any sense of a calling to serve was a long way off. Back then, Szymanski just felt lost in an expanse of empty space, searching for a north star.

Despite the musical interlude in law school, he remained more jock than performer. One of seven children — six boys — he grew up thinking of himself as an athlete. He came by it honestly. His father, Frank Szymanski ’47, had been an All-American center at Notre Dame, winning the 1943 national championship under Frank Leahy and the 1948 NFL title with the Philadelphia Eagles.

The elder Szymanski was a judge in the same courthouse where his son now serves. A painting in the building reveals a family resemblance so striking that a friend thought the younger Szymanski had his own portrait mounted while still serving.

Along with the likeness, Frank inherited an affinity for sports — at Notre Dame, “hockey player” was the heart of his self-conception — but not for the law. History was his thing in school. As graduation neared, unsure about what to do with that general interest, he sent out a couple dozen inquiries about teaching positions with a might-as-well shrug. A high school in Marquette, Michigan, deep in the Upper Peninsula, hired him to teach history and help with the hockey program. When a millage referendum failed three years later, his lack of seniority landed him a pink slip and left him rudderless.

“I just didn’t know what to do,” Szymanski says.

Law school became the fallback. Once enrolled at the University of Detroit. Szymanski got swept up in the competitiveness and finished top-five in his class. That led to a wining-and-dining recruitment by one of the state’s biggest firms.

“They fed me roast duck — I mean, what the f---!” he says. “What’s a Polish American guy eating duck? How about duck’s blood soup?”

Maybe that should’ve signaled how out of his element he’d feel there. As low man on the firm’s totem pole, Szymanski spent his time bobbing among waves of memos, mired in corporate drudgery. “I’ve never felt so out of touch with who I am as a person as those two years that I worked there,” he says. “It was like a waste of who I am — or I wasn’t who I am, I don’t know.”

Other clouds settled over his life during that professional malaise — a three-year relationship down in flames, hockey playing lost to an injury. A ray of light appeared in, of all places, the music video for “I Ran (So Far Away)” by the British band A Flock of Seagulls. Lead singer Mike Score’s instrumental contribution on the synthesizer involved little more than holding one finger on one key at a time. “I could do that,” Szymanski thought.

Soon he had his own synth — the source of an emerging pop sound he loved — and signed up for keyboard lessons. He wrote original songs that he played for an audience of his brother and friends. Days later, they told him, his music was still stuck in their heads, a sign that maybe he was onto something.

Not a new career, exactly. He left the fancy firm to start his own probate practice that his father, a judge in that division, seeded to get up and running. But it was making music that awakened Szymanski from his “flatlined” life.

Auditions to be a keyboard player with local bands went nowhere, but he really wanted to sing anyway. Heeding wise advice, he started his own band, Civilize the Wild. They built a local following with original songs and glam-rock covers, but as a side hustle it lasted only until other priorities intervened and members started drifting away.

For Szymanski, that experience marked the birth of Franklin Sane, singer-songwriter, who found in composing music — and especially in performing live — the fulfillment of an impulse deep within him.

“This was something I could dig. I had to be made for this,” he writes in a reflection on his musical journey. “I really got to be myself, whoever that is.”

To Patrick Daley ’74, a college friend and off-campus housemate, Szymanski has always been “enthusiastically and joyfully himself.”

Not long after graduating from Notre Dame, Daley and a few friends visited Szymanski in Detroit. On their way out of town, they followed him on his motorcycle to find the right route. As they parted, Szymanski pointed them on their way and bounded off toward the highway.

“He just blasts down the ramp — of course, no helmet in those days,” Daley says. “It looked like he was going 100 miles an hour, and I remember thinking, ‘God, that guy knows how to have fun.’”

Once Szymanski unearthed Franklin Sane, writing and performing became his main source of fun, the thing he threw himself into at high speed. At moments it looked like music might morph into a career. He produced albums of originals and covers, had promising meetings with record execs, made an appearance on a network show called Saturday Night Music Machine. “Came out of makeup with a glam-bam blow dry,” he says, “looking like a refugee from a Duran Duran boot camp.”

Visions of record deals, tours and groupies danced in his head. That’s where they remained.

He continued practicing law and led various bands that came and went on the Detroit club scene — The Bang Palace Orchestra, The Franklin Sane Seduction, Vision Town. If rock stardom never materialized, a sense of himself as an artist emerged in its place.

Songwriting and performing, first and foremost, were forms of self-expression, ends in themselves. But a mic plugged into an amp tethers singer and audience together, electricity that Szymanski feels with a jolt as a listener. Creating a similar sensation for enthusiastic crowds as a performer became its own motivation.

“I want them to feel like I felt when I was watching my favorite bands,” he says.

Which brings us back to where we started, a cool June night on an outdoor stage under the setting sun at the Cadieux Café in Detroit. Enthusiastically and joyfully himself, wearing a suit tinted purple by stage lights taking effect in the gathering darkness, he adopts another identity — that of Psychedelic Furs lead singer Richard Butler. A Furs aficionado in attendance says Szymanski has Butler’s vibes and mannerisms down. He stands knock-kneed, gripping the microphone stand as he sings, then bounds around the stage to boisterous whoops on tunes like “Love My Way” and “The Ghost in You.”

The band is its own opening act. After intermission, The Cinematic Furs give way to the Bowie-inspired headliner, Ziggy Moondust & The Spiders from Mars.

Night has fallen, drinks have flowed and the retro energy generated on stage — tech hiccups be damned — compel fans to their feet, calling out requests for songs they’ve long known by heart, dancing like they did when they were young and the music was new. It’s hard not to be struck by the juxtaposition of judge and showman. Bowie interpreted by a magistrate of the court. “Rebel Rebel” performed by The Man.

As Szymanski describes these parts of himself, distinct as they are in duty and demeanor, there’s a pay-it-forward refrain. He’s trying to move people in the same way others have moved him — musicians and motivational speakers and colleagues in the courts who value reconciliation over retribution.

“I want to do that for other people, too,” Szymanski says. “I want to share that level of difference-making, for want of a better term.”

Szymanski never wanted to be a judge. His brother Dave ’76 was elected to the bench in 1990. Frank helped the campaign, but he had established his probate practice by then and had music to make, so a judicial robe held little appeal.

Supporting his brother’s run introduced him to transcendent experiences in Detroit’s Black churches. Judge Szymanski, the patriarch, had supported Black attorneys and had personal relationships that Frank remembers as a United Nations of family friends and political allies. Because of their father, the Szymanski name carried respect in communities that seemed distant in culture and circumstance from their own.

Visiting the churches, ostensibly to meet constituents and distribute flyers, “was a really transformative experience for me,” Frank says. He’d stick the campaign literature on windshields and go inside for services, where the choir’s singing elevated his spirit like nothing he’d ever heard on a Sunday morning. “The music in Detroit churches? You gotta get out of town, man,” he effuses. “It’s sick.”

Those fervent spiritual sanctuaries and the staid judge’s chambers that his father and brother occupied would call to Frank in time.

Past age 50, when he married and started a family, Szymanski decided to move on after 26 years of shepherding probate cases through the legal system. “Transactional,” he calls that necessary if uninspiring work. “Somebody’s gotta do it.”

To become a judge would entail a pay cut, but freedom from the long hours of client service would offer flexibility to spend more time with his wife, Viktoriya, and their son, who was five months old when Szymanski was elected. Their daughter came along three years later.

“The way I describe it,” Szymanski says, and here comes that British accent again, “the Lord slapped me in the face and said, ‘Frank, your life is not about you anymore, you’re going to have to start opening your eyes to what’s going on in the rest of the world.’”

Probate was all he knew, but a judicial vacancy in the juvenile division looked like his best option. Elected in 2006, Szymanski expected to bide his time until a seat opened in probate. He issued campaign promises about making a difference for Detroit youth, which he meant from the heart and intended to keep, but he ran for his own family’s sake.

Once on the bench, he was seized by a sense of meaning he had never experienced in his professional life. Only a state statute that prohibits judges from running after age 70 will nudge him out of juvenile court when his term ends next year.

His legal and musical selves intertwined when he started showing up at Greater Quinn African Methodist Episcopal, one of the churches where he had felt so moved, for more than just campaign purposes. He felt alive there, aloft, carried along on the choir’s soaring harmonies.

The pastor invited Szymanski to play for the congregation, and the judge readily accepted. Week after week he returned with his guitar, “and the next thing you know, I was a regular part of the music ministry of Greater Quinn.”

There was the matter of telling his Polish Catholic mother about his new religious observation. How would a faithful St. Albertus parishioner take the news of a son she had raised there tending to his soul elsewhere?

Relating her reaction always brings tears to his eyes. She remembered music emanating from Black churches the family passed on their way home from Mass.

“We could hear the singing coming through the walls. There was something glorious going on there,” she said. “If you’re telling me that you’re going to be part of something like that, you have my blessing.”

Add yoga and meditation to the revelations that have altered Szymanski’s life — and that he wants to share with others, especially the troubled young people he encounters in court.

“These kids need some peace,” Szymanski said to himself early in his tenure, despairing over so many stories of abuse and deprivation.

He had done yoga himself and asked teachers around town how the practice could be incorporated into youth programs in and out of the justice system. They said meditation could make an even bigger impact.

That introduced Szymanski to a new practice. He found it powerful for emotional regulation and mental calm, and he now advocates for meditation to counteract the stress and trauma that accumulates in the lives of the young people who end up in his courtroom. It may be enough to keep them off the docket in the first place. His presentation “A Thousand Years of Wisdom” delves into modern applications of the ancient tradition that has shown promising benefits even for at-risk kids facing acute and urgent needs.

His experience in the role he expected to be temporary has turned into a permanent mission that will continue after he ages out of the judge’s chambers. “Even though I feel like I’ve had a fraction of the influence that I hoped to have,” Szymanski says. “I’m still pulling in that direction.”

His old Notre Dame friend Patrick Daley, a physician, has seen that firsthand in court. Visiting Detroit for a concert years ago, Daley met up with Szymanski, who invited him to sit in on a hearing. Specifics have faded over time, but Daley recalls a boy maybe 10 or 12 years old and facing a serious charge, standing with his mother before this elevated, black-robed representative of a system they expected to spit them out with institutional indifference.

“They had this defensiveness, this hostility,” Daley says. “They felt no power, like they’re getting effed over again.”

The judge’s understanding and patience proved as resolute as their defensiveness and hostility. In time Daley came to relate the exchange to his own struggle to show the compassion his cardiology patients deserved. Through the red tape of health-care bureaucracy and the rush of medical urgency, that essential element of caregiving could be overlooked too easily.

That comparison did not occur to Daley then. All he thought at the time was, “I witnessed humanity in an intense way. Something happened here.”

Yet he almost missed what happened, losing patience with the boy and his mother over their stubborn resistance to Szymanski’s entreaties. The judge was trying to guide them toward a redemptive ending to the story that had landed them in his courtroom.

They weren’t having it. Daley tuned out, frustrated with them for not taking Szymanski’s figurative extended hand. The judge’s forbearance never wavered. Little by little they began to trust that he had their best interests at heart.

“You could sense their spirit elevating, their feeling of power.” Daley says. “I could tell for Frank — he doesn’t even recall the case — it was nothing special to him, just an everyday thing.”

Szymanski’s everyday thing will change soon — at least his day job will. He once supported an effort to repeal the age-limit law, but its failure feels like a welcome exit strategy now, freeing time for work on behalf of Detroit youth that will take shape as he completes his final term.

“I gotta find some way to do what I want to do,” he says, “which I know is really more valuable than anything I’ve ever done.”

When a plan presents itself, Szymanski’s past suggests he’ll barrel headlong into it, music blaring.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.