Editor’s Note: On a peaceful Saturday morning in early September I sat in my backyard, savoring the scene before me: the grass and trees and black-eyed Susans, all feeling different now — as the sunlight and scents took on an autumn mood. It reminded me of a memorable essay from years back, and that got me to conjuring a list of all-time personal favorites published in the magazine over the years. I decided to share them with you, a new one each Saturday morning until the calendar reaches 2024. This week we have the painful and inspiring account, as told to Abby Pesta ’91, of Reverend Sharon Risher as she struggles to resolve her feelings toward the 21-year-old white supremacist Dylann Roof, who, on June 17, 2015, shot and killed nine African American congregants at Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston, South Carolina — including her mother. —Kerry Temple ’74

I was busy working as a chaplain at a hospital in Dallas, comforting a family who had lost their beloved grandpa, when my daughter started calling and calling. There had been an incident at Mother Emanuel Church, back in my hometown of Charleston, South Carolina. She didn’t know any details.

I knew something terrible had happened, something tragic. I said to myself: Sharon, think like a chaplain. You already know, without hearing the news, that people in that church are dead. You know it because you see it all the time at work. You’re always the one warning people: “The doctors are gonna come and speak with you now.” Later I got through to my baby sister, Nadine, in Charleston. She hadn’t heard anything, but she said, “I’m putting on some clothes and going down there to the church.”

Driving home that night, I faced the fact that my momma, Ethel Lance, would have been at the church that evening. There was a prayer meeting, and she would have been there. My mom loved that church. She worked as a sexton there, keeping the place tidy, seven days a week. Unless she was unable to get out of her bed, Momma would be at that church — you could count on it.

In my heart, I knew she was gone. I had to stop driving twice because I was crying so hard that I couldn’t stay on the road. Usually it takes about 25 minutes to get home, but that night it took an hour. I was trying to see through my tear-soaked eyes, straining to focus my vision. I kept calling everyone. Nobody knew.

When I got home, I saw the news on television. My heart stopped. A gunman had entered the church and started shooting. I never imagined such a thing. A man had murdered nine people at that historic black church. He had shown up at the door, and the worshippers invited him in. He targeted them because of the color of their skin.

My niece called around 3 a.m. and confirmed what I already knew: Momma was gone. In that moment, a scream came out of me. My dog started barking in confusion; he had never heard a sound like that from me. I learned that two of my cousins were gone too: Tywanza Sanders, a young man with an infectious smile and all the promise in the world, and Susie Jackson, a matriarch of the family and the church.

For the next two days, waiting for the coroner to release Momma’s body so we could plan the funeral, I could barely move. I sat in my apartment. I stayed in my pajamas. I couldn’t pull myself away from the TV — I wanted to see everything. In my state of shock, I kept thinking, maybe it was all a mistake.

During that time, there was a hearing for the killer, Dylann Roof; I hate to even say his name. Many family members of the victims attended the hearing. One by one, they stood up, faced him, and said, “I forgive you.” My sister Nadine was among them. I was watching all of this unfold on TV. When I heard Nadine say those words, I screamed again. Her words went through me like an electric shock. I was not yet ready to forgive. I felt as if she were speaking for the family, and I thought, How dare she?

I knew that, as a reverend, I should be one of the first to forgive. Instead, I was thinking like a brokenhearted daughter, angry at a heinous monster who had killed my mother. Why should I forgive? Yes, God commands us to forgive. But that’s not how I felt. I decided to take my time. I thought, People can judge me any way they want. I will get there when I get there.

My faith has carried me through many hurdles in life. But I did wonder, could it carry me through this? I loved my mother dearly. Her spirit flowed through every fiber of my being. She was killed in the most unimaginable of ways, in the most sacred of places.

Momma was 14 years old when she got pregnant with me. I never knew my biological father. My mom met my stepdad when I was about nine months old, then married him and gave birth to four more kids — Terrie, Gary, Esther and Nadine. I was the oldest, the only one who did not have the same father. But as a child, I was not aware of this. My mom never made me feel any different from anyone else. I always knew she would break her neck to help me do anything, to have anything, I wanted. It’s not that she went around saying, “You can do anything.” She didn’t broadcast it. She was not a warm and fuzzy-wuzzy kind of person. She was formidable. I just knew she was always beside me.

We lived in a black neighborhood on the east side of Charleston. The streets had historic names like Washington and Calhoun. It was a pretty run-down area; everything looked beat up. Parents worked hard. Kids played in the yard, or in the park — kickball, softball, jump rope. I walked to school in the morning with my siblings, after Momma helped us get ready. The school was right across the street from Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church — Mother Emanuel. Our route was peppered with people who knew our parents, especially my stepdad, Nathaniel Lance, who was quite the popular guy. His nickname was “Lima Bean.” He loved lima beans and could cook the hell out of them. Nobody cooked like Daddy.

Momma worked in maintenance at a convention center; Daddy was a skilled brickmason who later worked as a longshoreman on the Charleston docks. My parents lived paycheck to paycheck, but as a kid, I never really felt it. I just remember that it seemed like we never had enough space. We had one bedroom for all the kids, and the girls had to double up in bed. My brother always got a bed all to himself. I shared my bed with Esther, and she was always peeing in the damn bed.

My mom wanted a better life for her kids. She didn’t have much schooling herself, but she wanted her children to be educated. She would find free things for us to do, often educational events. She’d take us to programs at a local museum, or to a zoo in nearby Hampton Park. And on special occasions, when we got all dressed up and put on our Sunday coats, she would spray us with one of her perfumes. Then she would hide the bottle because she knew we’d be spraying it all over the place. Oh, she loved her perfumes. One time I bought her a fragrance at the local drugstore, Edward’s Five and Dime. It was some eau de something. It was stinky, but it was all I could afford. I was proud of buying that bottle of perfume; I bought it with my own money, which I earned from running errands for the neighborhood ladies. When I gave it to Momma, she acted like it was the best thing in the world.

I must have been around 6 years old when I learned that I had a different father than my siblings. It happened one day when we were visiting my grandma — my stepdad’s mom. She lived on Johns Island, one of the islands off Charleston. I was there with my siblings, playing in the yard, and she was sitting on the porch with a friend. I heard the friend say, “Who dat little red girl?” She meant me. I was lighter skinned than my siblings. My grandma replied: “That’s Lima’s child. Well, that ain’t Lima’s child, but he’s raising her.” It was the first time I really looked at myself and realized I was different.

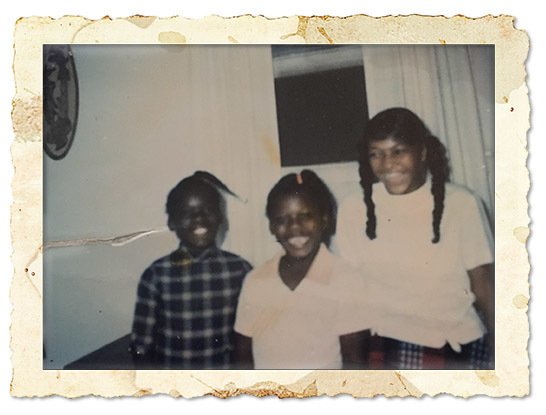

Sharon and her sisters, Terrie and Esther.

Sharon and her sisters, Terrie and Esther.

Around this time I started going to church. I went with my girlfriend Jewel from across the street. At the time my parents didn’t go to church, although they did encourage us to pray. Parents often sent their kids to church and stayed home themselves. Maybe that was the only time they could get any peace and quiet. Momma helped me get dressed, and I went with Jewel to the Macedonia African Methodist Episcopal Church. It was smaller than Mother Emanuel, with a relaxed vibe. I felt right at home there.

That church soon became a place where I felt peaceful and safe. I remember opening the doors and stepping inside, just feeling the warmth. I fell in love with the church, with its rollicking choir. Sometimes I would show up early for a choir performance and listen to the adults rehearsing in the back. I loved the sound of those voices, singing with such vigor. I realized that if I played it smart, I might get to join the choir, or read from Scripture. I didn’t know much about God. All I knew was that church was the place where people said God was. And I knew this God person was special. I wanted to please him.

Sometimes I wondered about my birth father. Who was he, really? There was this vague story I had heard from relatives: When Momma was 14, she had fallen for a young Puerto Rican man who wanted to marry her and move to New York. Her mother thought she was too young, and the couple split up. I believed this person to be my biological father. I tried a couple times to bring it up with my mom, but it was clear she did not want to go there. I just figured she had been so young when she got pregnant, she found it too sticky to discuss. But still I wondered.

In 1974, when I was a teenager, my mom got Jesus. That’s what we all used to say: “She got Jesus.” She started going to Mother Emanuel with my grandmother. Oh, she loved the church, which has one of the oldest black congregations in the country. I started going with her. The church was bigger and more formal than the little church I had been attending. Mother Emanuel catered to the more educated black people in Charleston, lots of teachers and lawyers. There, you dressed to impress. I would wear a fancy dress with stockings — a church dress. Our Sunday clothes and our school clothes did not intermingle, other than socks. I would sit in the back of the church and chat with my girlfriends — unless an usher noticed us. They were the side-eye people. You did not want the side-eye from an usher.

I remember the pride Momma felt when she became a member of the usher board. Ushers are an important part of the church. They are the gatekeepers. They’re the first people you see when you walk in the door. They help you find a seat; they collect the money and keep things in order. They wear a uniform: white or black, depending on the occasion, and white gloves — the whole deal. It’s all very organized, all about protocol. Momma was so proud to put on that uniform. She was an usher there for decades, and when she retired, she worked as a sexton, in order to help raise money for my niece Najee’s education when Najee’s mom got sick.

Perhaps Momma joined the church to help her escape from troubles at home. Daddy had become a functioning alcoholic. Sometimes they would fight, and he would get physical with her, or throw dishes. I was the oldest, so I would have to pick up the broken plates. The next morning, my parents would get up and act like nothing had happened. It was hard to watch my mom go through that, and I wondered why she would stay with him. She never wanted to talk about the bad things, though. She always said, “It’s okay. It’s okay.”

At school, our teachers were all black, and they instilled in us the belief that the way to succeed was to learn. I took that to heart. I knew I wanted to go to college, and would find a way to get there, even though my family couldn’t afford it. My teachers saw that thirst in me. They pushed me to excel. They told me I could get grants for college one day. And I did. After high school, I headed off to Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, North Carolina. I dreamed of becoming a lawyer. My parents drove me to the campus in their station wagon. We cried up a bucket when we said goodbye.

Risher as a high school senior.

Risher as a high school senior.

My senior year, I met Howard Bernard Risher. He was the brother of a girl I knew, and we met when I was home from school. Bernard was working on his master’s degree in psychology at The Citadel. He asked me for my number, and we went on a date — to see the movie Superman — before I went back to school. We stayed in touch over the months, talking on the phone. He came from a good family, had a solid education and played the saxophone in a band. I thought, Wow, I’m coming up in the world. Pretty soon, we fell in love. We wanted to spend all our time together. We talked about living together that summer, but our parents didn’t want us shacking up — especially his daddy, a pastor. I told Bernard, “Well, we might as well get married so we can shut them up.” He said, “Cool.” We wed before the end of my senior year, in June 1979.

I didn’t become a lawyer, and Bernard didn’t become a psychologist. We were young, and we thought love was enough to carry us through. And so we got a place in Charlotte and found jobs to pay the bills. I worked as a clerk at a Trailways bus station, then later in a one-woman law office for Miss Patricia King, where I learned to be a paralegal. Bernard worked for UPS. Within five years we had two kids — my son, Brandon, and daughter, Aja. We did all right, at least at first.

Tragedy struck my family a few years later. It was a Wednesday down on the docks in Charleston — payday for the longshoremen — and my father picked up his paycheck and got robbed. Someone hit him so hard that he fell to the ground and lay there, unconscious. A passerby reported there was a drunk man lying in the street. He wasn’t drunk. He was paralyzed. He would never move again.

He and my mom were separated at that point, but she offered to take him back. He said no, he could live with his mother. But my sister Terrie, who had been living in Charlotte, moved to Charleston to care for him. I begged her not to move back — I knew Charleston would not be fruitful for her. She was smart as a damn whip and had a computer science degree, and there were very few women in that field.

Sadly, my fears came true. Daddy was terribly depressed. For Terrie, something snapped, and she began to suffer from mental-health issues of her own. Doctors prescribed a drug to treat mood disorders, and she said it made her feel like a zombie. She continued to spiral downward, self-medicating with drugs. But eventually, something wonderful happened: Terrie started going to Mother Emanuel. She managed to get it together. She pulled herself up. You always knew, no matter what happened, the church was gonna keep you going. And it did.

As for my father, he died about a year after he was attacked. I think he willed himself to die. He would always say to me, “If I can’t be who I am, there’s no reason to live.” I would say, “Daddy, don’t talk like that!” But I know he wanted out.

Bernard and I made it through 19 years together before we fell apart. That was much longer than anyone had expected. Over the years, he was often out at night, playing the sax in local bands, and sometimes I thought he did it just to get out of the house. Along the way, we both became involved in recreational drug use; we started getting high to cope with stress. We had married so young, before we really knew each other, or ourselves, and then jumped right into parenthood. We often argued, and finally, we divorced.

Oh my, that was hard. I knew I had to get myself together for the kids, so I started going to a rehab program. My children needed me more than ever. My behavior weighed on my heart. God told me: You can do better than this.

That year, living in Charlotte, I turned to the church for real. Like my momma, I got Jesus. I had lost touch with my childhood enthusiasm for God over the years. After the divorce, my friend Anita invited me to a small, black Presbyterian church. I went with her and I felt the same warm embrace I had felt as a girl back home in Charleston. I started singing in the choir. I taught Sunday school. I became the president of the church’s women’s group. I felt like I belonged. Then I got a job as a receptionist in the Presbytery of Charlotte, the regional office of the church. I relished my role. A reverend, Dr. James Thomas, noticed, and he took me under his wing. He said, “Girl, you ever thought about the ministry?” No, I had never thought about it. You grow up thinking that people who are preachers are high and mighty. I started thinking about it.

When I entered the courtroom for the first time and sat 15 feet from the killer, it felt like pure evil.

And then, in 2002, a reverend named James Lee came to town, recruiting for the Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Texas. He said to me, “Come check out my school.” I went for a weekend, and I loved the leafy, serene campus. My soul said, Wow, this is the most peaceful place in the world. But my brain told me, You can’t do this. Reverend Lee told me, “Yes, you can.” And so I did. I applied for admission to the seminary, writing essays and gathering letters of recommendation. I still had my doubts, but God worked everything out. Every time I told myself I couldn’t do it, God stood there in the door and said, “What now? Just do it.” I got a scholarship and financial aid, and headed off to Texas. I felt like I was saving my life.

I never worked so hard for something, ever. I struggled through Greek and Hebrew. Four years later, at the age of 49, I graduated from the seminary with a master’s degree in theology. Momma came to Texas for my graduation, so proud. She knew that if I put my mind to something, I would do it. She’s the one who taught me I could.

Risher, graduating from seminary, and her mother, Ethel Lance.

Risher, graduating from seminary, and her mother, Ethel Lance.

I began training to work as a chaplain in a hospital. I thought I could put my life experience to use there, helping people deal with trauma. First, I got an internship at a Veterans Affairs hospital, focusing on substance abuse and mental health. I understood addictive behavior since I had gone through it myself. I spoke to people on the real. The hospital had a Sunday worship service, and in my first sermon I preached about how faith in God can help you stay steady in life’s storms. I also began preaching at a church in Dallas, again using my life experiences. In 2011, I flew home to Charleston to give a sermon at Nadine’s wedding — at Mother Emanuel. Of course, I wanted to preach the best sermon I had ever preached, to make Momma proud. Well, I went into that church and turned it out. My mom sat in the front row, crying and saying “Hallelujah.” I knew then that she really understood my calling. I felt like the prodigal daughter come home.

I got ordained, and in 2012 I started a job as a chaplain at Parkland Hospital in Dallas. I worked a second shift there, from 3 in the afternoon to 11 at night, in the trauma unit. I saw so many things. I saw people broken so bad, you wonder how they’ll ever recover. I was there, holding their hands.

And then my family suffered another trauma. In 2013, my sister Terrie died of cancer. Her death took a toll on all of us. After the funeral, when I was back in Dallas, I decided to ask my mom about my biological father, straight-up. I felt I needed to know the truth. I called her and asked, “Momma, do you know who my father is?”

She went quiet for a moment. Then she said, “I thought I would take this to my grave.” She proceeded to tell me something I could hardly wrap my head around. When she was a teenager, she had been raped by three white men. The year was 1958. Rape wasn’t something you talked about then — especially a black girl raped by white men. She was afraid to tell her own mom. And that’s how I came into the world. I was born of violence.

I could barely process what I heard. I didn’t talk to my mom for a couple days as I tried to digest the news. I wasn’t mad at her; she had been through hell. But I did feel hurt and confused. I was 55 years old; I had believed one thing for my whole life, and now I was hearing something different. My entire life was suddenly in question. I had always thought of my father as Puerto Rican. And it’s possible that he was — the man Momma was seeing back then could still be my father. Or my father could be a white man — a rapist. I will never know.

On June 17, 2015, Momma was struck by violence again. This time, at her beloved Mother Emanuel, when the gunman was welcomed inside. After two days of being flattened by shock and grief, I had to muster the strength to travel home to Charleston for the funeral. I told myself: Get up. Get yourself together. Shit gotta be done.

It was the longest plane ride I ever had. When I landed, I felt like I was in a fog. How could this be happening? Then things got even more surreal: At the memorial service for Reverend Clementa Pinckney, I met the Obamas. President Obama seemed like a regular kind of guy. With him being the highest officeholder of the United States, you might think he would be a little standoffish. But no. He’s very approachable. And he smelled good, too; I wish I knew what cologne he used. I thought about how Momma would have given her left eye to meet President Obama. And here I was, standing next to him, because of her.

When I returned to Dallas, I could not get back on my feet — literally. It turned out I had broken my ankle while trying to break up a family scuffle. My colleagues at the hospital were less understanding than I would have hoped. I needed to take some time off to recuperate, and they were eager for me to come back full-steam. I thought, How can you not understand what I have been through? We are supposed to be chaplains. Can’t you care for one of your own?

I thought all the time about Momma. I remembered how, the last time I talked to her, she had described a new perfume she wanted. She called and said, “Ooh, I smelled this Banana Republic perfume. I sure would like to have some of that.” So I bought it for her, but I didn’t send it right away. That bottle of perfume was delivered to her the day after she died. The thought of it haunted me.

My faith was put to the test in a more profound way than ever before. Sometimes I prayed so hard, and other times I couldn’t pray at all. For a time, I stopped going to church. I felt overwhelmed. I knew in my heart and in my head I would return because I had no other choice. But I kept thinking: Why, God? Why? I talked to my kids and to my sister Esther all the time. I talked to the other families who had lost loved ones at Mother Emanuel. Ultimately, because of my faith and the faith of the people in that church, I was able to continue to get out of bed.

As the rest of the country grieved the tragedy, the issue of the Confederate flag arose, in a big way. On my birthday, July 10, the flag came down from the Capitol in South Carolina. It came down on the backs of those nine people who were killed. My first thought was, OK, Momma, what a wonderful birthday present you gave me. Before that, I hadn’t given a whole lot of thought to the Confederate flag; I just knew it was something that should not have been up there. We had reached a point in America where that symbol wasn’t cutting it anymore. When the flag came down, I felt a wave of pride. Momma helped get that done.

I have never seen a Scripture passage that lays out how much time it takes — or how much time God allows us — to forgive.

In time a doctor told me I should take a little more time off to recuperate from everything. When I told my boss, she was not pleased. My brains exploded. And then, a calm came over me. I said, “After prayerful consideration, I’ve decided to hand in my resignation.” I could imagine Momma going nuts in heaven, jumping up and down, saying, “Girl, you gonna give up your good job?” Yes, I was.

I moved to Charlotte to live with my daughter. I began to rest, and to try to heal. I began speaking at events; I met Spike Lee. I traveled to Washington, D.C., for an event at the White House with Everytown for Gun Safety, an advocacy group. I met people who understood how I felt because they had been through it, too. I joined the ever-growing chorus of people calling for more common-sense laws to keep people safe.

The federal trial of the killer began in December 2016. I knew I had to go and represent Momma, even though it would be terrible to sit in the same room as the gunman. And so I traveled to Charleston. I felt like I was preparing for battle. The Feds talked to the families of the victims, preparing us for what to expect in the courtroom. I knew we would be hearing all this hideous stuff. You have to hold your head up. When you’re in a room with pure evil, you stand up with your head held high.

When I entered the courtroom for the first time and sat 15 feet from the killer, that’s what it felt like: pure evil. I sat with the families of the victims. As we listened to the details of what had happened to our loved ones, it felt as if scabs were being ripped from our bodies. But if you got emotional, you would feel a comforting hand on your back, or the person next to you would hold your hand. We had all formed such a bond. Nobody’s family was more important than anyone else’s. We were all in this together.

I got up and forced myself to go to court every day. Sitting there in the stifling courtroom, reliving the nightmare, I would tell myself: Just hold on. It’s gonna be over with. You can go back to the hotel tonight. You can sit by the water and watch the boats. Then I would go to the water and cry. There were always guards around us everywhere; we were being protected.

To make the situation even crazier, the families of the victims were staying at the same hotel as the defense team. One day I was walking down the hall in the hotel when a defense lawyer stopped me. I had been all over the national news; I’d said I didn’t believe in the death penalty. The attorney said to me, “Reverend Risher, I just want you to know how much I appreciate your stance on the death penalty.” I didn’t reply. I felt he was representing evil. I figured he would use my words to help the killer, saying, “See, even the families of the victims don’t want the death penalty.” I walked away.

When I testified, I talked about how my mother’s murder had left the family in tatters, how the fabric of our family had been torn apart, how I prayed we would come back together. I didn’t look at the killer. I looked out into the crowd and tried to keep myself together and not sound like a blabbering idiot. Afterward, another defense lawyer spoke to me. She said, “Reverend Risher, your testimony was so powerful.” I came to realize that the defense lawyers were just doing their jobs, and of course they have emotions, too. They were reaching out to me as human beings, as people who have hearts, not as people who represent evil. You see, God works on you. He allows you to go through those human emotions. He knows you will come back to the spiritual side.

For weeks I endured the courtroom hell. I learned for the first time that, when Momma was shot, her cellphone fell out of her pocket and slid across the floor. That’s the phone that one of the survivors, Polly Sheppard, used to call 911. Even in death, Momma was still trying to help somebody. The families were given the opportunity to speak to the killer in court, and so I did. I spoke of the victims, saying, “I pray those nine people visit you every night and do Bible study with you.” I looked at him. He didn’t look back. I knew he wouldn’t. He didn’t look at anyone. That understandably bothered some people, and they would scream at him to look at them.

Throughout the trial, I kept my eye on the jury. I was afraid something insane would happen and he would go free. You never know. When they found him guilty and sentenced him to death, I felt like there was a party in my brain, with balloons and all kinds of craziness happening in there. And then, just as fast, I felt numb. People hugged and cried. It was over. Time to go home.

I went back to my daughter’s house in Charlotte and rested, giving myself time to try to heal. I started speaking at colleges and churches around the country, which has helped me to move forward. I preached about how violence and hate turned my world upside down, but hope and faith in God helped me keep going. As for forgiveness, I was not quite there yet. I continued to give myself the time it took. I knew I would forgive one day because God mandates us to forgive. I have never seen a Scripture passage that lays out how much time it takes — or how much time God allows us — to forgive. But I knew I was getting there, gradually. I could feel it. The anger was fading with each talk I gave. I felt surrounded by love and supported by the people who came to listen.

Last fall, while I was preaching at an interfaith service in Martinsville, Virginia, I finally said the words: “I forgive him.” Tears flowed down my face. I had to pause for a few moments to regain my composure. I hadn’t planned to say it. It just came out. But I had been thinking about it, and I knew I was ready. The time had come. Time to let it go. In saying the words, I felt freed from the grip of anger and grief.

The Rev. Sharon Risher speaks out against gun violence at a news conference in June 2016, at the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. Photo: Zach Gibson/The New York Times/Redux

The Rev. Sharon Risher speaks out against gun violence at a news conference in June 2016, at the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. Photo: Zach Gibson/The New York Times/Redux

I thought about my mom, about how I used to sleep in her bed with her when I went to visit in Charleston. We would lie there together and just talk. The thought of it made me smile. I remembered how I used to call her and chat about everyday things, the latest sermon at Mother Emanuel, the best way to cook gumbo. I thought about how, one day, when I get to heaven, oh, what a day it will be. What a day it will be when I get to see my momma again.

Reverend Sharon Risher continues to speak about gun violence and the Charleston church shooting that took her mother’s life. Abby Pesta, a former intern with this magazine, has written for a wide range of publications, including The Atlantic, Glamour, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and Newsweek. She is the co-author of How Dare the Sun Rise, which recounts a young woman’s escape from a massacre in Africa and her flight to America.