The sun set hard that night, no more willing to give up the day than we were. We watched it wallow, fat and low, taking its time as it blazed over a steel sea greater than anything called a lake has the least right to be. We breathed in air so fresh and clean it seemed a crime we hadn’t paid for it, or for the right to be there at that time, in that place, just me and my eldest son, together with a chance to understand in a visceral way that stillness is not silence, and that time, however flexible, is finite.

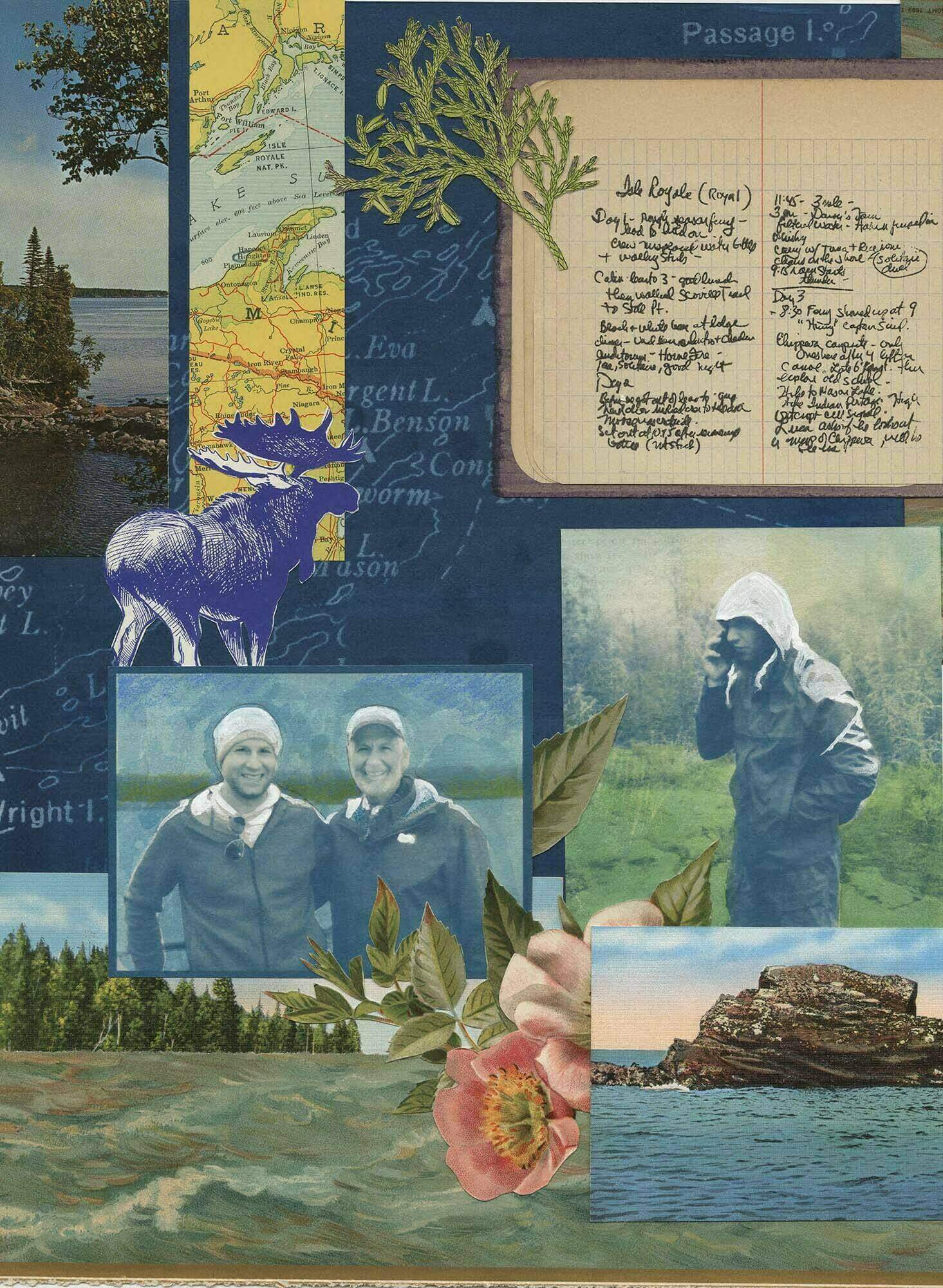

We were at Moskey Basin, Michigan, on the rugged, U.S.-facing flank of Isle Royale National Park, one of the most remote parts of America. After hiking since dawn our muscles throbbed, our feet ached and our backs begged for mercy. But the crystal waters of Lake Superior drew down our discomforts even as they chilled the flask of whiskey we had anchored in the shallows. With the ear of my heart set to the lakeside breeze I heard only the determined paddling of a family of ducks. I looked around and saw no one but my son, and I felt our bond fortifying as surely as if forged by fire.

I couldn’t have imagined the simple magnificence of this scene months earlier, in winter, when Aahren ’04 first told me about this trip, because I hadn’t then been part of the plan. He and a colleague in his corporate law office in St. Louis had put together a challenging itinerary to test their resilience, a week-long journey of endless walks beneath overloaded backpacks, eating industrial-grade, freeze-dried food, suffering through nights coiled in lumpy sleeping bags, and waging war with legions of mosquitoes and black flies so fierce that Aahren and his friend had been advised to drench their clothes in potent chemical repellents weeks before embarking.

Their destination? Isle Royale — despite the spelling, it’s pronounced “royal” — the least visited national park in the Lower 48. Only a few parks in Alaska and one in American Samoa attracted fewer visitors last year than the 25,454 who braved the trip to Isle Royale: a modest day’s attendance figure for more popular and accessible places like Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Grand Canyon.

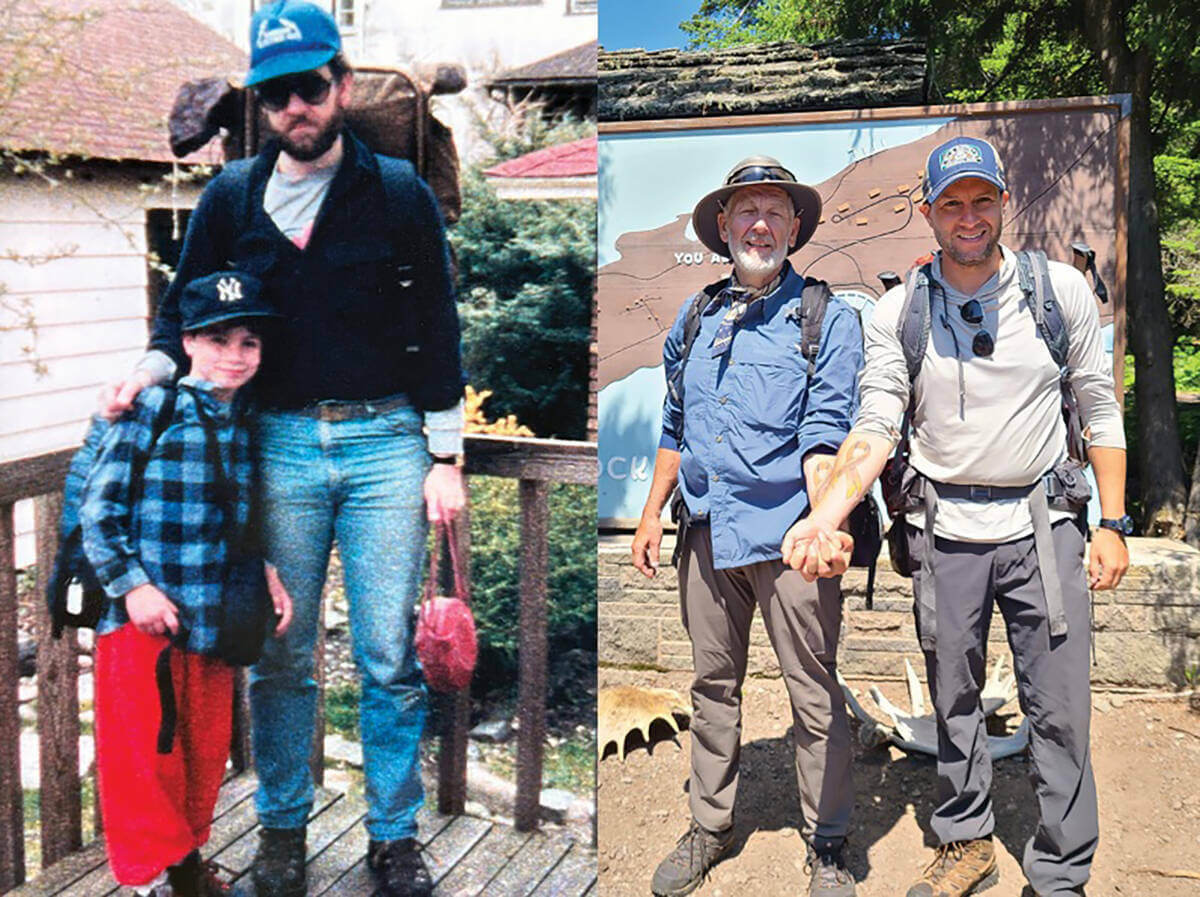

From the outset I could understand their motivation even if I didn’t share their desire. It’s what men do — taking the measure of yourself by pitting your energy, stamina and strength against the greatest challenges you can find. That’s essentially the lesson of scouting that Aahren had learned from Cub Scouts through Eagle Scout, earning that rare distinction after blazing the first public hiking trail in Mexico’s Ajusco Mountains while we lived in Mexico City.

I also thought I knew how much he needed to make this trip. He had just gone through a difficult divorce that was as disorienting as it was disturbing. He was handling it the way he’d handled other challenges, not the least of which was overcoming a devastating illness that was diagnosed during his first days as a freshman at Notre Dame. This latest setback had been a true reckoning for him, but also a kind of awakening to the real stuff he is made of. For the first time, he was willing to speak openly about the disease that had sidetracked him years before. He even went as far as to have his right forearm tattooed with the date of his diagnosis and the single word “Unstoppable” over the orange ribbon that symbolizes leukemia awareness.

I went with him to the tattoo parlor and, to show my support, had the artist give me the same tattoo on my left forearm. But I was relieved that I wasn’t going on his Isle Royale adventure. We’d hiked together from the time he was a Cub Scout, with him trying to keep up with me as we made our way through the New Jersey Pine Barrens or the bluestone mountains of the Western Catskills. On my own, I’d hiked across the Grand Canyon and many sections of the Appalachian Trail.

But that was a long time ago. My backpack is as old as Aahren, and most of my kit is hopelessly outdated. Around the time that he planned to be hiking I would be marking my 70th year on Earth, and the notion of Isle Royale and all Aahren had told me about it made me eager simply to hear from him how it went.

Then, well along in the preparations for their odyssey, his friend apologized and backed out. Aahren was determined to go on his own. I had not the least doubt he possessed the skills and the strength to handle whatever Isle Royale could hurl at him. But hiking with a partner is a standard precaution. Moreover, it hurt me to think of him out there alone, especially when he was getting back on his feet. So I swallowed hard before I called to tell him that if he would have me, I’d like to come along.

He agreed, and as soon as he did, I started to feel differently about the idea. I reveled in the anticipation of being with Aahren for an entire week without distractions, with no mission but to be out in the woods under star and sky, keeping our presence in the forest as ethereal as possible. More than anything, I realized what a blessing it was that he wanted to be with me.

As most fathers eventually find out, keeping up a relationship with adult offspring takes effort, especially over long distances. It’s not exactly Harry Chapin’s “Cat’s in the Cradle,” but it’s not easy. Both of you are busy. There are duties and commitments to spouses, kids, bosses. You can try to bridge the distance using FaceTime or Zoom, but it will never substitute for physical closeness or make up for time lost. There’s something about being in the same place, doing the same thing, that simply cannot be duplicated.

Aahren took care of the plans, securing passage on the ferry from the Michigan side of Superior. He even borrowed new, high-tech equipment from the same friend who couldn’t make it so that I wouldn’t have to struggle with the stuff gathering dust in my attic. He had a fancy self-inflating air mattress, a sophisticated internal frame backpack and a ridiculously small camp chair that hardly seemed worth carrying. I cleared my schedule, booked a flight to St. Louis and made a few trips to REI to top off my gear. As the getaway drew closer, we huddled often on the phone or in emails, going over the finer points of backcountry meals, sharing hints on boots and socks and insect repellent, and agreeing to split the food so our packs would weigh the same.

I flew to St. Louis, and we took turns driving the 12 hours to the King Copper Motel in Copper Harbor, Michigan, where we’d spend the night and pick up the ferry the following morning for the 60-mile voyage to the island. We woke to gauzy skies and whitecaps on Superior that brought back some of my initial worries about the trip. Before boarding the ferry, I asked one of the crew about conditions on the water. He just shook his head and said they sold Dramamine at the nearby concession. We bought some.

Good thing, too. By the time we boarded, the only seats we could find were backward-facing — the worst position to be in if you’re a landlubber like both of us. About an hour out, we took the pills. Aahren still turned green, and I had to shed my jacket. The crew passed out plastic bags, but thankfully neither of us needed them.

Two pretty rough hours later, our ferry slipped past Raspberry Island and through Smithwick Channel to dock gracefully at Rock Harbor. The only developed part of the island, it has a standard-issue National Park ranger station, gift shop and bathrooms. The rangers were outside collecting backwoods itineraries from all hikers because the island is so remote they need to know who hasn’t come back when expected. A cheery ranger gave everyone a quick orientation, urged plenty of caution and lots of water, and wished us all a good trip.

When John Steinbeck wrote about his search for America in Travels With Charley, he wisely observed: “We do not take a trip; a trip takes us.” As soon as we left Rock Harbor, the brawny serenity of the island took us in and didn’t let go for the entire week. There was something liberating in a soul sense about being on a primitive island in the middle of that ocean of a lake, without roads or cars or most of what is the stock of our lives back home. Once we got on the trail, we’d be isolated from every other human being, relying entirely on the supplies on our backs and each other.

We dropped our packs at a screened-in lean-to and took a short introductory hike along the Stoll Trail to Scoville Point, around four miles there and back, with enough rock and water, brush and sky, wildness and wet, to leave us eager to hit the trail for good.

We woke the next morning to the rustling of a moose as it lumbered through our campsite. Moose would be our constant though mostly invisible companions, their ubiquitous droppings documenting their endless wandering. Wolves inhabit the island, too, and though we never saw one, there were times when we sensed them watching.

Finally it was time to hike. We hoisted our packs and I heard myself grunt like an old mule. The backpack Aahren’s buddy had lent me was beautiful — a work of art, really — but fully loaded it felt like I was hauling a side of beef. I adjusted the straps to pull it closer to the curve of my back, but with each footfall the dead weight bore down on my shoulders, squashing my back and punishing my knees. When Aahren said, “You lead,” I was ready to insist that I should take the sweep position that I had always had when we hiked, keeping him in sight and letting him set the pace. But the load forced me to reconsider, and reason soon trumped vanity. I moved to the front determined to set a brisk pace that showed no weakness.

Our trail skirted Superior’s jagged shoreline, a long series of deceptively difficult twists and rocky, haphazard turns. I’d stop for a minute to catch my breath and Aahren would pull out his water bottle, take a swig and wiggle it at me until I shook my head no. Even with a crisp breeze whipping off the lake, we were drenched by the time we stopped for a few bites of the 2-foot-long pepperoni sticks that would be lunch for the week.

Back on the trail I tried changing my gait, taking longer strides and keeping my knees bent. I felt better, but it didn’t last. My pack seemed to be getting heavier and the unwelcome thought crept into my mind that I might not be able to finish. When my legs started to cramp, I had to swallow my pride and ask Aahren to hold up.

“You OK?” he asked me, concern he couldn’t hide in his face. I was as disappointed as I was embarrassed, worrying that with so many miles to go that day, and through the remainder of the week, I’d let him down.

It was then that it hit me: We had switched roles. He had my back just as I used to keep an eye on his when he was small. He is stronger than me now, smarter and tougher, too, which is every father’s wish, but not one we necessarily want our sons to see.

By the time we reached Daisy Farm, our first scheduled campsite, we both knew that I had allowed myself to become dehydrated. But when Aahren dropped his pack, I could see that he seemed fresh and strong. He stayed with me just long enough to hector me about not drinking enough water before declaring he was ready to fulfill another one of his goals for the trip. I followed as he bounded down to the water’s edge and jumped in. At that time of year, the water is no warmer than 50 degrees. I thought for a second about joining him, but my ankles were already blue.

That night rain rolled in, cooling things off. Next morning a water taxi took us to Chippewa Harbor, which a ranger had told us is his favorite spot. From the side of the island we were on, it could only be reached by boat. Once we got there, the ranger’s judgment made absolute sense. This was that mystical mix of woods and water that I had imagined Isle Royale to be, a scene from James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales that had captivated me as a boy. A trail led from the dock up the side of a hill, and from there we looked down on the dark, calm water of the harbor, green-black under the overcast sky, and across to an unbroken citadel of noble white spruce and balsam firs, their limbs intertwined so densely that no light seeped through. We were the only people there, a cathedral in mid-week, silence echoing and reverent light sparking the shadows. The daylight was a prayer; I felt like we should kneel.

Aahren’s plan called for setting up camp there, then hiking several miles to Lake Richie and back. But first he was determined to look for something he’d read about — a long-abandoned one-room schoolhouse that a few pioneering families had used during the Depression. He led the way, and after a few wrong turns we found the dilapidated shack. Some attempt had been made to preserve it, but the forest was winning this battle. There wasn’t much information about the school inside the shack, but Aahren was delighted to have found it, putting real images to a tale.

We started on the trail in a warm drizzle that turned into a cold and steady rain. We pressed on through a forest primeval, beneath towering white cedar and lanky paper birch, around waist-high bearberry and prickly rose bushes that grabbed at us as we passed. Soon we were soaked, but it mattered none, because with no other destination that day, our pace slowed, allowing us time to take in every sight, to listen to every sound, to feel the freshness of each raindrop as it splashed our faces.

I know some hikers are obsessed with distance just as others focus on speed. But I follow the guidance of the 19th-century naturalist John Muir, who held that people ought to saunter through mountains. In a famous account, Muir told a friend that in the Middle Ages, when pilgrims passed through small villages on the way to the Holy Land, locals would ask where they were headed. “A la sainte terre,” they replied: “To the Holy Land.” Muir probably made up that etymology of the verb “saunter,” but he lived its meaning, usually being the last man back to camp whenever he walked. “These mountains are our Holy Land,” he told friends, “and we ought to saunter through them reverently, not ‘hike’ through them.”

Aahren and I walked in Muir-time, stopping to check side trails that led nowhere, comparing flowers and weird ferns, quietly sneaking up on Lake Richie in time to see a bald eagle alight from its nest.

By the time we returned to camp at Chippewa Harbor, the rain had stopped. As the sun worked its way back to us, we both understood that it was critical that our boots and socks dry out before we hit the trail again. We laid them on a rock. Then we set up the tiny folding chairs I had initially mocked. A foot high and weighing little more than a pound, they seemed too flimsy to be worth the effort. But as we settled in and opened the Basil Hayden Dark Rye we’d carried, no plush movie-theater recliners could have offered more comfort. We watched the colors change over Chippewa Harbor and talked easily about the trail, the rain and the old schoolhouse.

None of those words are here because I did not record them. Taking notes seemed a self-centered act during this time when we were sharing everything. Besides, it really was what went unsaid that turned out to be most meaningful, like when Aahren set out to make a fire to help dry our clothes. He pulled out of his pocket a piece of birch bark that he’d picked up along the trail. A curl of birch bark is the finest fire starter because it will catch like it’s been dipped in gasoline, even when wet. I’d passed that tip to him long ago, and he had clearly absorbed the lesson — a part of me that, I now saw, has become a part of him.

We set out early the next morning, retracing a stretch of the same trail we had taken in the rain. By now I was matching Aahren drink for drink every time he stopped for water, and I never suffered another cramp. We took the steep Indian Portage Trail that crosses the island and turned north. Occasionally, I even asked him to take the lead while I matched his pace. Walking behind, I could see how his heavy pack clung to his broad shoulders. Just how heavy it was I didn’t realize until one night when we were cleaning up after dinner and I moved it. I understood in an instant that we hadn’t shared the load equally as we had agreed before leaving St. Louis. All along he’d been carrying a good deal more weight than I was, but he’d never mentioned it.

Even with our John Muir pace we arrived at Moskey Basin with plenty of sunlight left in the day. It’s an oddity of time management that although the island is so far west, it lies in the Eastern time zone with the rest of Michigan, meaning that daylight lingered until almost 11 during our visit: The sun, too, was on Muir time. We camped at Moskey’s magnificently isolated shoreline and changed into swimming trunks, even though we had no intention of jumping in. But we stuck our tired legs, feet and backs into the bracing water and dropped our whiskey bottle in to chill it. Later we set up those weird little chairs and simply enjoyed being there together. The whiskey went down a thimbleful at a time as we talked and talked — about Aahren’s kids, about the divorce, about his work and his happiness. He told me he was fine, that the disruptions in his life were temporary. Work was challenging and enjoyable, with raises and promotions ahead, and he felt his exercise regime had prepared him well for the hike. At times we said nothing, and it was OK. He was OK. Getting through it all. Unstoppable.

The week went like that, hiking, talking, luxuriating in each other’s company. It was easy to spend time together, easier in some ways than it had been since he wore that dark blue Cub Scout uniform. And I was awed as I watched him one day, step after step, mile after determined mile, with his cellphone in hand searching for a signal so he could call his kids. We were on the Greenstone Ridge Trail, walking some of the highest parts of the island, when he latched on to a signal from Canada and checked in with home, describing for them where we were and making sure they were all right.

On our next to last morning on the island, Aahren and I circled back to Rock Harbor, half a day ahead of schedule. I knew then that he must have eliminated the most grueling parts of the hike once he knew he’d be with me instead of his friend. He’d customized the trip to make it easier for me, just as I had undoubtedly done for him when he was a Cub Scout. Even so, the 50 miles of trail we had hiked tested me just as Aahren and his pal had expected it would test them. Our equipment had functioned flawlessly, our planning had been pinpoint accurate, we had outwitted the mosquitoes and black flies and, with the exception of a few blisters, neither Aahren’s youthful physique nor my besieged and scarred body had let us down.

A few months after the trip, I visited Aahren in St. Louis and he showed me a copy of a book he’d found online. It was The Diary of an Isle Royale School Teacher, written by a young woman who’d spent a Depression-era year teaching at that one-room schoolhouse we’d explored at Chippewa Harbor. It’s not great literature, but it evoked the ruggedness of existence on the island and its savage beauty. The teacher had admired it as much as we did, although after spending the winter there, she was desperate to leave and never went back. Reading about the places I visit is a secret joy I’ve long treasured. Seeing Aahren do the same made me realize how much more I’d passed along to him, sometimes without even trying.

Obviously he knows that as a writer, I have a special kinship to words. My books have come with us wherever we’ve lived. Besides the riches they hold, I like having them near me, as though I am in the company of family and friends. In much the same way, I’ve grown used to being near trees. To walk under their shade. To breathe in their scent. To contemplate their yearly cycle of death and life as their yellowed leaves drop around me on crisp autumn afternoons. For me, trees and books are connected because of the almost spiritual way both can teach, comfort, challenge and provide what I, at times, seem to need most. It was on Isle Royale that balsam firs and paper birches brought Aahren closer to me than we’d been in years. Sharing that small book helped me to look at him and see myself.

Aahren is different from me in many ways — and thank goodness for that — but we share this need to be outside, to be surrounded by trees, to appreciate the books that trees beget. We came to this trail from starting places so dissimilar they have almost nothing in common. I grew up in a congested city near New York where, even when you were outside, it always felt like you were inside, and I did not discover my affinity for the outdoors until I was an adult. Aahren was in diapers when my wife and I first brought him into the woods, always with his picture books in tow. Divergent trailheads, yet following the same trail.

He’s already planning our next great outdoor adventure, this time with me and his younger brother, Andrés. I’m extraordinarily proud to have the chance to share so much time with both of them, and with our daughter Laura, who also seeks out the woods and invites me along.

Aahren is the leader of his son Luca’s Cub Scout troop, and when his daughter Penny’s Girl Scouts need help, they call him. I look forward to the day we can bring them hiking with us. I’ll do my best to keep up, though I suspect I may need to offload more weight and buy some of that ultralight backpacking gear. If we follow trail rules and have the slowest set the pace, I’ll end up at the head of that three-generation pack, sauntering through some forest somewhere, still awestruck by trees that tower far above us, still scouting for trail markers and sunning snakes and stray curls of birch bark to tuck into my pocket as we wander along paths that take us far but never end.

Anthony DePalma, a former correspondent for The New York Times, is author of several books, most recently The Cubans: Ordinary Lives in Extraordinary Times.