It’s been so long since I’ve been in Winslow, Arizona, that the last time I was here only Dick Tracy had a cell phone. In the 1970s, I often hitched rides back and forth from Notre Dame to my home state with one of my California classmates. Along the way we’d pick up Interstate 40, slip an Eagles cassette in the player and soon enough we’d be in the high desert standin’ on a corner in Winslow, Arizona. Naturally I’d fill out postcards, noting that Winslow was such a fine sight to see, whereupon I’d scurry on over to the post office for a hand stamp. An old hand at such requests, the postmaster would ever so carefully stamp each card so as to make a perfect impression.

My extraordinary efforts did not go unnoticed by my friends, who would then expect cards from other neat places in our travels. One year we even got our kicks on Route 66, sending cards from Amarillo, Gallup, New Mexico, Flagstaff, Arizona. We didn’t forget Winona, Kingman, Barstow, San Bernardino, either. Poor Winslow. Overlooked by Nat King Cole, it could have been famous in two songs, which would not have been bad for a mountain town of 10,000.

Traveling through small towns and deserts taught me to be attentive, to look for unexpected beauty. One road marker might lead to something as enduring as the dignified gnarl of a 2,000-year-old bristlecone pine, while a rest stop 700 miles down the road might reveal a moment as stunning and ephemeral as a gila woodpecker with its red zucchetto poking its head briefly from the black-crusted cavity of a saguaro. My grandparents lived their last decades in the Mojave, where delectable beauty might amount to something as simple as entering their front door to find the house suffused with the kitchen aromas of pyracantha berries and citrus simmering into Christmas jelly.

One August a couple years ago, I started off driving solo through California’s great Central Valley, hitting farm towns like Lodi, Turlock and Chowchilla, then turning east and crossing the Mojave Desert and Joshua Tree National Park before landing at Needles, California, on the border of Arizona. Two hard days on the road led me past cholla and greasewood to hills of scattered juniper and finally up into pine forests until I reached Flagstaff at nearly 7,000 feet. From there an easy descent took me back down into high desert scrub and Winslow once again.

For the record I will confirm that any stay in Winslow is better than getting stuck in Lodi again, for Winslow’s summer days, while comfortably hot, are seldom scorching. I have no idea what the residents of this idyllic town do other than, I hope, sit back and enjoy life. I hope they called it paradise. And so far as I know there are no songs about Turlock, Chowchilla or Needles.

So here I am sitting on a corner in Winslow, Arizona, texting all my friends of a certain age, playfully bemoaning the fact that no one is slowin’ down to take a look at me. Some cop somewhere should have given time a speeding ticket, for it cannot be that four-plus decades have passed since four guys who first worked together as Linda Ronstadt’s studio musicians and touring band began writing songs together. The Eagles’ first single, “Take It Easy,” has become one of the most lasting songs on American radio. Their Greatest Hits became the best-selling album of the 20th century for decades, outselling any album by Sinatra, Elvis, the Beatles, Barbara Streisand, Michael Jackson or Garth Brooks.

If no one’s slowing down to take a look at me I suspect it is because I am now more than 10 years older than the in-town speed limit, and I am thin of hair and have a paunch. So I was not really under the illusion that anyone other than a cop on the late swing shift would take a look at me. During my hour of texting, no girl — or middle-aged woman — slowed down, either. Still, in such moments one can’t help but think that it would have been nice.

My texting done, I decide I’ve still got some road left in me. It’s a perfect night to be a midnight flyer, to open the windows, crank up the music and rock on down the highway to the next town. The deer and the antelope might not like the Eagles, but it will bring me a peaceful, easy feeling to reminisce about yesteryear’s cross-country drives. A little over an hour later and road weary I pull into a charming adobe hotel in Holbrook, Arizona, and bunk down for the night.

Come the morning I am up early, a rarity in my life since I am an inveterate night owl and, as a professor of English and humanities, I’ve been able to avoid scheduling early morning classes. Today, though, I simply don’t want to miss out on a free breakfast.

At one table in the breakfast area, a young mother is in charge. Her two preschool boys, each with a blond Mohawk, have learned early on in life that a woman with Indian feathers tattooed around her arm and a three-inch Native American dream catcher dangling from her neck is not to be messed with. “Guys, can you sit still for just one minute?” she says, more gentle command than request. Her husband looks like he is on leave from the military. Having followed his marching orders he hands her plastic utensils for four, which she distributes. For but a second I catch the hint of a smile. If one is attentive to the moment, one might discern an aura of deep beauty here as this mother brings breakfast to her boys and order to her world.

Another table seats a lively foursome. Two girls appear to be sisters, big sister in her mid-20s, little sister around 15 or 16. Big Sister’s boyfriend looks like he’s headed to a weightlifters convention. He stands quietly at the breakfast bar waiting for his waffle to finish cooking. A younger fellow is sitting next to Little Sister, though I cannot tell if he is Little Sister’s boyfriend or brother or perhaps the weightlifter’s younger brother. He jokes around a lot, plays with packets of sugar, and Little Sister laughs. I feel out of place, like the new kid in town.

I set my writer’s journal on a table and head over to scout out my breakfast options. Toast-your-own English muffins. Check. Biscuits and gravy. A possibility. Fruit cups. I snag the last one with peaches. The waffle machine in front of the weightlifter beeps twice. He rotates a handle, which turns the griddle upside down, allegedly making it easier to remove the waffle from the skillet. I’ve never seen such a contraption before, but I gather that’s the theory.

“It looks tricky,” I say.

“There’s a set of instructions on the back,” he says, pointing. He’s guessed I can read, I think with some weird kind of satisfaction, until he re-aims his finger and points further back saying, “There’s even pictures.” I’m deflated. This is not a good start to my morning.

At that instant the 15-year-old girl shoves out her chair, pops up and steps over. “I can do it,” she says. “Let me make your waffles!” I glance over at Big Sister, who smiles. Muscle Man steps aside, and before I can say a word my new friend says, “It’s really pretty easy. I can show you.”

Given the world we live in today, I do not want to seem as thrilled as I am, and I am fully enchanted. “I’ll go make my tea while you take care of the waffles,” I tell her. “How’s that sound?” If I could have, I would have dunked this sweet girl in my cup and my tea would have been perfect.

Tea in hand, I plop two biscuits on my Styrofoam plate, add a scoop of gravy, pick up a pair of paper packets of pepper and return to my table. A minute later my newfound friend places four neatly arranged mini-waffles before me. “Here you go — perfect waffles,” she says. “I didn’t know if you wanted butter or not.”

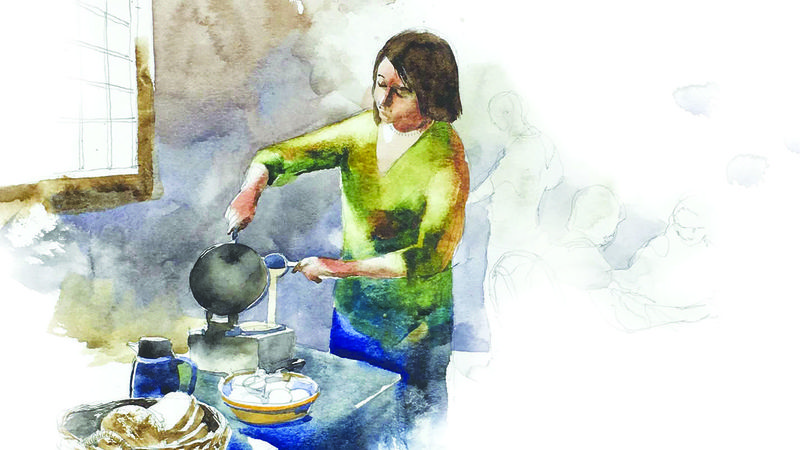

“You can’t beat the service here,” I reply. Big Sister smiles. But what I really wanted to say was, “Yes, they are the most perfect, most glorious, most wonderful waffles ever,” for that was the real truth of the moment. I also wanted to offer this beautiful girl in Holbrook, Arizona, a bequest: “Someday in your life, please go online and look up a painting called The Milkmaid by Jan Vermeer. Or, better yet, go out into the world to a place called Amsterdam and see that painting in person. Something inside you will stir. I can’t tell you why, but somehow you will feel things you understand yet cannot quite put into words, at least not at first.”

An image becomes sacred when it points beyond itself to what it might mean for something important, like love, to be ‘incarnated.’ This beauty that points beyond itself accomplishes something other, something more than mere decoration.

Yes, that is what I want to say. That will be my gift to her, my payment for these most perfect waffles, these waffles without butter. But I fear to say such a thing, and it’s of no matter for she is already gone, returned to her table where the young man again seeks her attention. In a moment they scoot out their chairs, clear the table and depart.

So I cannot give my tribute to the 15-year-old girl. But I realize I can still give this gift. I will return to school in the fall and forevermore in my Intro to the Humanities course I will tell this story to my students. I will tell it to them when we look at Vermeer’s The Milkmaid, a painting students usually encounter with a “That’s nice, but so what?” reaction. Since I teach in a public community college, many of my students are parents. They juggle work, family, school, life. They want to know why things matter. Every day I teach, the question “So what?” is important to my audience.

Once back in class, I turn out the lights, go online and project onto a big screen The Milkmaid, which saturates the room with its color and presence. “It’s nice,” they say. Nothing more. Pens move, fingers tap. The Milkmaid. Vermeer. 1657-58. They’re ready for the next image; they’re ready for the test question. Or so they think.

“This is not ho-hum stuff.” I pause. “What’s really going on here?”

Students describe the obvious: a young woman leans slightly over a table; she is pouring milk. Ho-hum. That’s still all they see.

“Can you say anything about her attitude?” I ask. Thirty looks of bafflement stare back at me. “If she were pouring the milk for us, which she is in fact doing, what could you say about the way she is pouring? Give her a job evaluation.” Education comes down to the job market these days, it seems. Someone hesitantly offers that the milkmaid pours the milk with exquisite care, then adds, “as if what she is doing in that moment really matters.”

“It does matter.”

Someone else makes a connection. “Maybe this is an image of love.” Then there is an eruption of recognition. Vesuvius has just blown its top! Vermeer has shown us one of life’s great insights: If we love, many of our mundane acts of love will go forever unrecognized.

The students with children instantly relate. Every day they pour milk for their own small children, who will play with their cereal and splatter the liquid on the high-chair tray or on the floor. They know the mess on the floor does not clean itself up, and The Milkmaid becomes something more than just a “nice” picture.

One student might point to the breaking of the bread on this table; another might note the dominance of purples in the painting, purple like grapes and wine, and the round purple nodules, suggestive of grapes, decorating the container to the left. For my secular students I note that Vermeer was Catholic and that Catholicism emphasizes its beliefs and spirituality in concrete ways. It’s why Catholic churches are full of statues and icons, I tell them. An image becomes sacred when it points beyond itself to what it might mean for something important, like love, to be “incarnated.” This beauty that points beyond itself accomplishes something other, something more than mere decoration.

“If the deepest part of yourself were a piano,” I say, “a work of art is the hammer that strikes the wire string that makes the sound that resonates in your soul. When perfectly struck, that sound compels you to stop whatever you are doing and listen. Sometimes you hear a command that says only ‘pay attention’; sometimes you hear a command that says ‘dance!’”

This distinction between the “niceness” of decoration and the deepest levels of meaning, especially of meaning that arcs from the temporal to the ethereal, is a new concept for students who have never set foot in any church. It is an eye-opener for those who have come through 12 years of public education, often without much if any exposure to art. Suddenly art begins to make sense in a new way, and symbolism is something more than just playing “the hidden meaning game.” Vermeer opens wide a whole new world; Vermeer changes them. We have moved from ho-hum to wow.

Our discussion invariably leads me to Mother Teresa’s famous line about doing small things with great love. We pour milk. We break bread. We share wine. We serve one another, sometimes with the humility of love, oftentimes without hope of recognition or reward. We intuitively feel that acts of love are of intrinsic worth.

At this point I bemoan the fact, again, that I missed the opportunity to say all of these things to the lovely young woman at the adobe hotel in Holbrook, Arizona, as if this whole discourse was really all about her and about how I sure blew it that morning. And then, because teaching, like great art, should not be too heavy-handed, and because I would not want my students to think I am as serious as I am about this moment — for that would make it all seem too much like a lecture — I break into song: “So I’m sittin’ at a table in Holbrook, Arizona, such a fine sight to see, when a girl, my lord, at a flapjack board, slows down to make some waffles for me. Come on bay-ay-by, don’t say may-ay-by, ’cause I know that your sweet love is going to save me.”

The class will groan. One person will quip, “Berberich, better not give up your day job.” Another will throw in, “You wouldn’t last 10 seconds into your audition for The Voice.”

But it’s a set-up. I will reply, “But it’s true; it’s all really true. Remember that the next time you’re on I-40 in Arizona. Stop for a while in Winslow. Send me a card. Text me. Tweet me. Email. Call if you want. But if you call, I’ll expect you to sing. Because from this classroom, from this college, from this moment on your job in life is to go out into the world and sing. Or if not that, at least pour milk like it matters. Or make every waffle a most perfect waffle. Find a place to make your stand.” That’s all you need to know. Everyone who learns that much gets an A.

Michael Berberich teaches writing, literature and humanities at Galveston College, Galveston, Texas.