The greatest gift my father may have ever given me came as a byproduct of a wish — he wanted me to be a hunter. Scratch that; he wanted us to hunt together as father and son. Which we did for many years, until puberty and interests such as girls, tennis, guitar and my peer group drew me from his world into another. I was fishing with him as early as age 3; at 7 carrying a BB gun as we skirted a cornfield for doves; by 9 crouching in a duck blind with my pint-sized 410 shotgun at the ready; and at 11 sitting next to him up high in a tree blind as we hunted deer.

People who have issues with hunting do not understand hunting as I experienced it. For our family it was nothing out of the ordinary that at 3 I could be quiet and still in a boat, understanding if I dropped my soda or banged my rod, the boat’s metal hull would conduct the sound through the water and send the fish scurrying. By first grade I knew how to scan a trail for snakes, for copperheads and rattlers. I was never afraid of them because my father taught me how to see them, but also because I knew he would see them first.

In the third grade I was carrying a firearm that could kill my father. I remember the weight of that knowledge as I followed him down a path, realizing if I made a mistake, followed a dove’s arc toward him, I could pull the trigger at the worst possible moment. Picture me, tiny for my age, in camouflaged hunter’s gear and hunting boots, stepping after him down some tracing of a path, already skilled in walking softly and freezing at the sight of incoming birds.

But the biggest test of my skills as a hunter — which more than anything is really the skill of being still, of blending in, of waiting — was deer hunting. When I was 11 my father drove us from our home in Grand Prairie, one of the suburbs of Dallas-Fort Worth, down to his lease in the Texas hill country. I carried my 410 shotgun for show; it would be useless for deer.

A few years later he bought me a rifle small enough to manage, a Winchester lever-action 30-30. Although we often saw deer from the blind, I never witnessed him firing a shot, though I would fire one at 14 years of age, a stunning, perfect, single bullet that would drop my only deer some 30 feet from where I hit him. The deer was young, antlers just sprouting. Somehow with this event my time as a hunter ended. At least that’s how my memory frames it. I may have gone hunting a few times afterward, but I know my heart wasn’t in it. I’m certain my separation wasn’t for regrets or feelings of guilt at taking the life of this creature. The shooting of the deer seemed more of a conclusion. My focus shifted. I still would not take the shot back.

But I’ve jumped ahead. I want to go back to age 5. Or 6 or 7. To consider the hours I spent fishing in the boat with my father, walking beside him hunting doves, hunkered in the duck blind waiting for the birds to fly in. I sat beside him in the tree blind and never saw him shoot, or shoot at, a deer.

Deer season lasts, more or less, 12 weeks, and my father hauled his gear down to the lease almost every weekend, taking me with him once or twice. By the end of the season he would have brought home three deer — two does and one buck, the limit allowed by law. The older bucks with trophy racks tend to lie low. They move from brush to brush. They know they’re being hunted and will hang back and let the does cross a clearing first to draw fire. During an entire season you may see only two or three deer with trophy racks, and my father sat in the blind passing up good shots, waiting for the right deer, usually bringing him in on one of the last weekends.

Mornings at the lease I would wake to my father nudging me at 4:30 a.m. as he set a cup of coffee beside my bed in the cabin or trailer or whatever he and his deer-lease pals had rented. On particularly cold nights water might freeze in our glasses, but by the time I crawled out of my bed and my feet hit the freezing floor he would’ve already fired up the stove and cooked breakfast — scrambled eggs and toast and more coffee. Soon we were driving in an open-top Jeep, a tiny green thing, an army toy, the headlights feeling their way through the darkness as it rocked across the dirt and grass, and the stars overhead ridiculous in their number, unbelievable, gaudy except for their beauty. We left our cabin so early and in total darkness because we had to park the Jeep, walk many yards away from it to clear ourselves of its presence, climb up the trunk of a tree, and situate ourselves atop a flat wooden platform at least 30 minutes before the sun rose to let the dust we’d kicked up settle and our scent dissipate. Otherwise we would see no animals.

I think now, more than anything, my father was there to see animals.

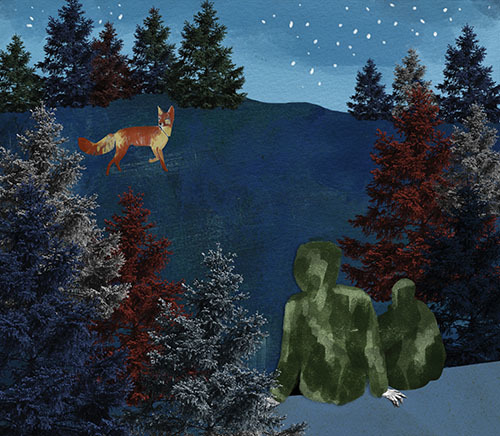

Picture me beside him, our feet hanging off the platform’s edge. The sun starts to rise. The blues streak through the black, and the sky opens. This is the best, most beautiful moment of the day, and the next hour will provide the most likely shot we will have.

Here is how you manage your presence on the deer blind: You scan from side to side in the smallest increments possible looking for movement. You don’t move your hands, your arms, your legs. You’re bundled, but your face is freezing. At some point your nose will start to run. You let it run if you can stand it, but if you can’t, you move your gloved hand in the slowest possible increments to your face to capture the effluvia. You do not sniff, as any deer would pick up that sound. You press your glove to your nose, then, in increments, lower it back to your side.

At some point during that first hour your toes will start to go to sleep. They will hurt, they will curl, they will sting. But you cannot wiggle your feet as that would wiggle your boots and alert any animal nearby to movement in the tree. But you can wiggle your toes inside your boots. And so you wiggle your toes, which at least slows down their falling asleep, and incrementally bring your glove to your nose again to wipe away the snot and lower it, also incrementally. You live incrementally for the longest time. It becomes your discipline, snot and extremities be damned.

Perhaps my most favorite moment (yes, I chose that construction): The birds had just erupted into sound with the first light, and by our tree, gullies claimed by the early fog creased the grass. My father had a way of tapping my knee with the back of his hand and gesturing toward something he wanted me to see, and as he tapped me I saw it, too — a fox, the only fox I’ve ever seen in the wild — bounding out of the fog and gullies and disappearing back into them, drawing reddish arcs with its body in the blue light.

The Germans have a word for the discipline it takes to hunt — sitzfleisch. It is translated variously as “The ability to endure or carry on with an activity”; “A person’s buttocks; the power to endure or to persevere in an activity; stamina”; “The fleshy part of the human body that one sits on.” You have to love the Germans. They can invent a word from anything through the pieces of their language. Length is of little importance as is sometimes elegance, but still they can name the thing that needs naming. There were, and are, many Germans in the Texas hill country where I hunted with my father.

Sitzfleisch has to do with being still, with waiting. It has to do with being able to maintain one’s focus through discomfort to the other side of discomfort; with learning that this is the work, and if you can do it, something surprising may appear. An animal.

So I learned to stay with discomfort in order that a deer might appear that I didn’t have to shoot, or a flock of ducks might lift the wind as they swept over my head, or a fox might arc through fog in the gullies. What astonishes me, in retrospect, is I had the discipline to do this as a child, from ages 3 to 14, withstanding boredom and discomfort. And because I was taught that this behavior was normal, expected, I learned sitzfleisch.

Years later the discipline came into play as I drove my little red car back and forth down I-35 from Grand Prairie to the University of Texas at Austin. The 200 miles seemed an immense distance, and I was miserable the first hour, bored, anxious, worries batting around in my head. I’d turn on the radio, then switch it off, then turn it on again, wondering how I was going to manage my irritation. Finally I would shut it off and just sit through the discomfort. Because on one of these drives I’d learned that at some point if I stayed with it, and it might take a damn long while, something would change. When it did, my experience was as if the world relaxed. And I’d take a breath and wonder at the colors in the sky and the hills, and at how I was traveling at 70 miles an hour down an open road. I’d see birds curling through the air and clouds shapeshifting. It was a kind of meditation, though I didn’t know it then, a kind of slowing down, and by slowing down I could witness things that moved deeper than the rat-a-tat firings of my brain. A lone tree on a hill could appear miraculous. And why not? Isn’t it?

I learned to meditate. People who’ve never tried it don’t understand that during each session anxieties and concerns are flying through your mind, and that the calming or releasing of this chatter can feel like a kind of work. What the experienced meditator knows is if you sit with the discomfort of the day’s thoughts pressing in at every angle, a moment usually comes when the mind slows down. Some days go easier than others, but that’s not what matters. What matters is your showing up and sitting down and beginning.

Late by most standards, at age 25 I discovered I was a writer. It was an accident. I was at The University of Texas, lost regarding who I was and what I might do; so lost, in fact, I’d majored in acting. But I was no actor, and after two years — we were juried — I was asked to find a career more suited to my talents, or lack thereof. Only because during my final semester a movement teacher had us recite poems while jumping around the dance studio, I discovered modern poetry. I was stunned by what was possible with words and incredulous as to why I’d been so underexposed to it.

When I followed this experience with a poetry-writing course, I knew I’d found my home. And the most obvious talent I had, or skill might be a better word, was this ability to sit through discomfort, to be still, to produce steady work, whether good or bad. It wasn’t until years later when I was getting my MFA in creative writing that I found out from classmates that sitzfleisch wasn’t second nature for many, if not most writers.

Being able to sit through discomfort is one of the most important skills a writer can develop. Day after day you must sit somewhere, public or private. You wait. You stare at the screen or paper. You try things. You chase leads and follow your characters and instincts. You try something else. You get coffee and come back, move words around on paper. You don’t push for an end, for completion, for relief. Or at least you try not to, because on some level there is no relief. On some level you don’t want relief. You want to sit with your process, your work, your story, your material. You scribble or tap away until your allotted time is up or you’ve put down your required word-count for that day. However you mark your progress. You walk away. The next day you begin again.

My experience coaching writers has shown me this can be learned at any point. As in hunting, you don’t look for a quick shot from the deer blind. You don’t look for completion and relief and the trip back to the cabin in the Jeep. Even if your toes go to sleep and your nose starts to run. You sit with the process day after day until it becomes habit. Until the time spent in your creative space becomes the goal. Until you’re not yourself without it. Blank page or no. Words moving or no. Story working or no. You sit. You scribble. You fill the page with nonsense if that’s what it takes to get things moving. You accept your discomfort. You practice this, over and over, and get better at it. Not perfect, but better. One day, after you’ve put in so much time that no one but another writer, or maybe a hunter, would understand, a character you’re working with makes a decision that surprises you. So you follow the decision to see where it might lead. Down the path that has opened unexpectedly. Down the storyline.

Suddenly, an animal appears.

Steve Adams lives in Austin, Texas, where he is a writing coach (steveadamswriting.com). His memoir, “Touch,” appeared in The Pushcart Prize XXXVIII. He also has been published in Glimmer Train, The Missouri Review, The Pinch and elsewhere. His plays and musicals have been produced in New York City.