It’s rare for a historian to see her work make any sort of impact outside the classroom, let alone evoke tears of gratitude. So I was surprised when my research into a Second World War resistance network set off deep emotional reverberations.

Between 1942 and 1944, the Dutch-Paris escape line, what Americans would call an underground railroad, rescued approximately 3,000 people from the Nazis. The 330 men and women in Dutch-Paris had very little in common other than a refusal to accept the hate-filled demands of the Nazi occupation. They lived across Western Europe, spoke several languages, belonged to a variety of faiths and represented the range of social strata. Yet together they hid Jews in occupied Belgium and France, smuggled Jews, resisters and downed Allied aviators to safety in neutral Switzerland or Spain, and operated as a clandestine courier service for people of goodwill.

Even without arrests or reprisals, the double life of resistance took an insidious toll. Most Dutch-Paris resisters stayed in their homes and jobs in order to do the illegal work of rescue. A banker, for instance, could not move money around for the network if he did not go to his bank. A civil servant could not forge identity papers without using the forms and rubber stamps kept in the town hall. To be of help, these otherwise ordinary people had to lie routinely to the authorities and their neighbors, use false identities, buy food on the black market, exchange currency outside legal channels, ignore the curfew and commit other crimes. Although the goal of rescuing the persecuted justified these lives of falsehood and dissimulation, it corroded the resisters’ sense of themselves as honest citizens. So many months of maintaining a respectable façade, when every act of kindness toward a fugitive counted as a crime and threatened danger, could not help but leave psychological scars.We may now recognize resisters as the great moral heroes of the 20th century, but during the war they were hunted as criminals by an array of Nazi and German authorities, paramilitary collaborators and national and local police. The men and women of Dutch-Paris rescued anyone who needed help, but in doing so they put themselves and their families at risk. The posted punishment for assisting an Allied aviator was the execution of all the men in the resister’s extended family and the deportation of all the women to concentration camps.

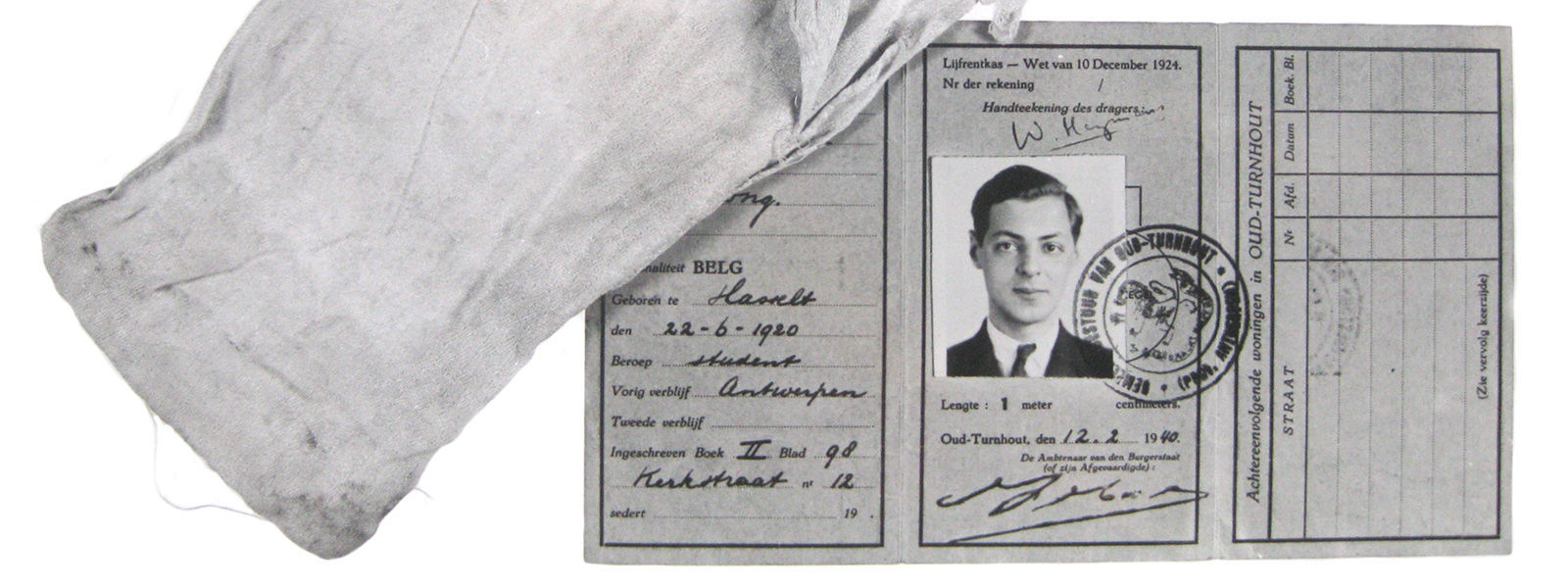

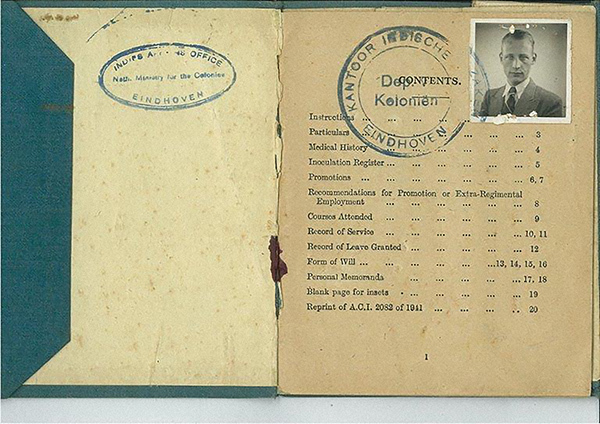

The peril escalated for the leaders, couriers and guides who had to go underground. These men and women traveled around occupied Europe for months or years with assumed identities, using false documents and constantly changing addresses. They did not carry ration cards at a time when it was illegal to buy a meal without one. They could not openly visit their families. Despite careful planning and unremitting courage, a few of the fugitives they were helping were caught. Starting in February 1944, many of the resisters themselves were captured.

German police would arrest 68 men, women and teenagers belonging to Dutch-Paris, torturing most of them and deporting over half to the concentration camps. Those who survived would return in miserable health, in some cases to homes the Nazis had stripped bare of anything of value, including the wiring. A few had left behind children who had been cared for by friends or had weathered the last year of the war on their own. One resister’s teenage son got lost while his father was in the camps and remains on the Dutch list of wartime missing persons to this day.

Being a resister during the Second World War could be as traumatic as being an infantryman. Yet for the most part, their traumas have remained unacknowledged. No one offered these heroes emotional counseling. After all, the world lay in physical and economic tatters all around them, and millions of people were displaced or dead. At most, resisters received medals or pensions. Only the most politically astute received any public recognition, because resisters made the majority who had not stood up to the Nazis uncomfortable.

Like many combat veterans, the survivors of Dutch-Paris rarely spoke about the war for complex reasons. Willy Hijmans explained the most common to me. He had been a medical student until the occupation authorities shut down the Dutch universities, leaving him more time to find hiding places for Jews and to join the line as a courier and guide between Holland and Belgium. He stopped his resistance activities only when a faulty V-2 rocket landed in his home in The Hague, putting him in the hospital until the Allies arrived. By 1945, he and his friends wanted to be done with the war. They wanted to finish their educations, start families and live their lives.

Joke (pronounced YO-ka) Folmer told me she had wanted to live for the future, not the past. As a teenager she guided hundreds of downed Allied aviators across occupied Holland, passing a few of them to a schoolmate in Dutch-Paris. She might not ever have told her children what she’d done if some of those airmen had not later made public efforts to thank her.

Hijmans, who saved many lives, also told me that he hadn’t done anything worth mentioning, that he should have done more. Similarly, Anna Zurcher said she had done only what was “normal.” The mother of an infant, she had welcomed Jewish refugees into her home near the Swiss border while her husband, Jean, served as a border guide and a courier for illegal documents. The family knows of three occasions when he escaped arrest by a hairsbreadth.

Needless to say, what they did for strangers was anything but the norm. Anna Zurcher meant that it was what any decent person would have done, but then she had an optimistic view of human nature.

The resisters who survived torture and imprisonment had more painful reasons for their silence. Some simply could not endure remembering or speaking of those experiences. Others had learned harsh lessons. Alain Souloumiac told me that his mother’s closest friends were other resisters she had met in the concentration camp at Ravensbrück. Those women survived the Gestapo and the SS because they had trained themselves to lock their minds. They never escaped that burden of secrecy. For them talking was dangerous, possibly even an act of betrayal.

The official narrative of victory over Hitler reinforced these nonviolent resisters’ disinclination to talk about their illegal work. Escape lines like Dutch-Paris had opposed the Nazis by defending the value of all human life and specifically by rescuing the persecuted. But that story did not interest those who shaped public memory. Political agendas required that people think of the war and the resistance as purely military endeavors. Rescuers like an unmarried, middle-aged secretary who hid Jewish families in her apartment had no place in that story.

By the time I started researching the war in 1989, this official military version had seeped into the common understanding. The French villagers I met were surprised anyone would want to know about their experiences. For them, the “war” meant the soldiers and partisans who were lauded in political speeches and written about in military history books. It was not housewives finding food to put on the table, or children missing school because there was no coal to heat the building. This same public narrative of what counted as war — the military fight — muffled public understanding and discussion of the resistance. Few nonmilitary resisters protested this sidelining. It was enough that they knew they had done the right thing.

But traumas so deep find expression even if the only voice a person will give them is silence and the only audience is the person’s family. Such silences can take many forms. Some resisters transformed their experiences into black holes — compelling but empty — that their families orbited around. Others told stories but kept hidden their most painful memories. Their children might not have known exactly what happened, but they could tell that certain subjects were off limits. They realized that the anniversaries of unknown events made their parents sad. They could hear that Dad had nightmares. They could see that Mom trembled at border crossings and avoided trains. They learned how to contort themselves to the shapes of those silences.

The pain shimmering in the silences could have a powerful effect on children’s imaginations. Indeed, they could become burdens on children who did not want to add more suffering to what their parents had already faced. This anxiety sometimes led them to impose a crushing perfectionism on themselves in their attempts to be model children who could somehow fix their parents. Some tried to act as parents to their mothers and fathers, often with debilitating effects.

The rise of neo-Nazism and Holocaust denial in the 1980s compelled some Dutch-Paris resisters to break their own silences. Willy Hijmans and Piet Henry, for instance, contributed to an anthology of wartime memories written for Dutch schoolchildren. Another courier, Anna Neyssel, spoke and wrote widely in her adopted country of Sweden about her resistance work, her capture by the Gestapo and her tribulations in Ravensbrück as testimony to the evil of Nazism.

There were those resisters who were not silent, who told their survival stories over and over, even taking their children to the important places of hiding or escape. And yet all of these stories were incomplete, because no one knew the full story.

Dutch-Paris was a clandestine and illegal network that opposed a ruthless occupation force. No one, not even the leaders, knew everything about how the network functioned, or who was involved. Imagine the consequences if someone who knew everything had been tortured. At a minimum, hundreds of Jewish men, women and children would have been discovered and killed. After the liberation, the leaders had the clout and resources to investigate the wave of arrests that decimated the line. But even they did not learn the complete story.

By the time I began my research into Dutch-Paris in 2009 the purely military narrative of the war had begun to crumple, in large part because the children of those involved, the “second generation,” had come into power. They wanted to know what really happened, so they opened the archives. When I researched my first book in France in the early 1990s, I needed special permission from the Ministry of Culture, the national police and the chief archivist to read any archival document from the years 1939-45. Any document. Today anyone may consult almost anything from the war years that does not impinge on the privacy of a living person.

This was certainly good news for me and made it possible to rely on archives and documents rather than on interviews with survivors or their families. After all, I reasoned, I would not likely find many people still alive with firsthand knowledge of Dutch-Paris. Even if I did, understanding and memory shift over time. Documents written in the 1940s, however, would always represent what people knew and thought in the historical moment.

Thirty-one archives in seven countries and four languages later, I had reconstructed most of the story.

Although I worked in solitude, my research kept gathering followers, starting with the archivists. Of course a historian always hopes that archivists will take enough interest in a project to offer a suggestion or two, but almost all of the archivists I spoke to put extra time and thought into helping me. The archivist at the Dutch Red Cross shared his desk with me for weeks while I read through files that he dug out of the vault. Then he called his counterpart in Brussels and got me into the inner sanctum of that archive. The archivist at the Bureau Résistance of the French defense archives, where researchers are permitted three files per day, let me come early, leave late, browse the card catalog reserved for staff and see as many files as I wanted.

Occasionally one or another of these archivists still refers someone to me or my blog, How to Flee the Gestapo. I started the blog as a place to tell the stories that didn’t make it into the book. Eventually I also used it to offer advice about how to research resisters and downed Allied airmen. In return I’ve received messages from people in Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Europe, the United States and Canada.

Every once in a while a correspondent shares information that never made it into the archives. Robert F. Anderson found my blog when he was looking for the address of Gestapo HQ in Brussels. He was one of the 10 Allied aviators arrested at the Dutch-Paris safe house there in February 1944. Without Anderson I would never have found the names of those captured aviators. Nor would I have known about the rogue jail and interrogation center that the Geheime Feldpolizei — the secret military police — operated on the Rue Travesière.

For the members of Dutch-Paris and their extended families, my book — published in Dutch translation as Gewone Helden, or “Ordinary Heroes,” in 2016 and in English as The Escape Line in 2018 — is much more than “history.” It is a key to their family and personal identities.

No one has been more dedicated or enthusiastic about sharing the story than Maarten Eliasar. In 1942, Eliasar’s father and grandfather left their home in the Netherlands rather than report for deportation “to the east.” They made their own way almost as far as the Swiss border, where they found help from Dutch-Paris resisters. Maarten, born after the war, grew up calling the leaders of the line “Uncle Jean” and “Uncle Moen.” But all those stories of courage and sacrifice weighed heavily on him. He felt responsible for his parents’ happiness.

And there were holes in the narrative. The most gaping involved his grandfather, Simon Eliasar. In December 1943, Simon was captured by German troops in a mountain village in France not far from Switzerland weeks after arrangements had been made for his escape. He perished in Auschwitz within the month. A framed photograph of “Papa’s Father” stood prominently on the family mantel, but Maarten and his siblings were not supposed to talk about him or ask any questions.

In 2016, Sierk Plantinga, a Dutch archivist and historian who was helping Eliasar prepare the Dutch translation of my book, found a collection of photographs of the graffiti etched into the walls of the Drancy transit camp outside of Paris from which Simon and tens of thousands of other Jews were deported to their deaths. One of those photos revealed a message that found its recipient 72 years later: Simon had scratched his name and birthdate along with the initials O.Z.O. into a wall. “O.Z.O.,” for Oranje zal overwinnen — the Dutch royal House of Orange shall triumph — was a resistance slogan. Those three letters gave Maarten a sense of his grandfather as a real man with a positive spirit, a man who defied the Nazis. For the first time he could be proud of his courageous opa — his grandpa.

Later that year, Maarten Eliasar organized a minisymposium to launch Gewone Helden. We invited everyone he knew to be connected to the line or interested in the topic and everyone I had encountered through my research. On a blustery day in November, nearly 300 people ate cookies and drank coffee in the lobby of the Amsterdam Hilton while the Israeli ambassador’s security detail swept one of the ballrooms.

The plate glass windows that line the outer wall of that ballroom look out over the grassy bank of a canal, but those gathered were focused on the wartime photos of people and places I displayed to illustrate the Dutch-Paris story. They listened intently as four well-known Dutch intellectuals commented on the line’s legacy. We finished by presenting copies of the book to representatives of the families of 13 resisters and to Joke Folmer, that intrepid guide of downed Allied airmen. When the last of the 14 received the book, everyone in that ballroom stood up and applauded thunderously. It was a testament to the heroism of the men and women of Dutch-Paris and to how the war had shaped the lives of everyone present.

The guests then returned to the lobby for the reception I missed while signing books. One gentleman purchased 17 copies so that everyone in his extended family would understand what their father, grandfather or uncle had done. But I did make it to the private dinner for “Children of Dutch-Paris,” by which we mean anyone with a family connection to the line. Not every relative I met that day chose to attend, but some 60 people sat among the linen tablecloths and softly gleaming cutlery. It was an elegant dinner made memorable by the emotion filling the room.

These people had come from the Netherlands, of course, but also from the U.S., Sweden, France, Germany, Spain, England and Switzerland. Even though they spoke different languages at home and had lived vastly different lives, they felt a kinship to one another. In the snatches of conversation I heard, people were establishing their connections through mothers who had exchanged Christmas cards for decades, or through vaguely remembered childhood visits. My talk had given them the context for the family stories that had shaped their lives.

A Frenchman captured the mood in a toast he made to what he called his long-lost (and possibly never-suspected) family: the Children of Dutch-Paris. This man had ignored more than one politely formal letter from me during my research. His grandfather had died young from the lingering effects of imprisonment in a concentration camp, and his grandmother bitterly resented what she felt had happened because of his involvement in the escape line. A historian did not interest her grandson, but meeting other people who’d grown up in the line’s shadow did. The realization that he shared a childhood of odd silences and volatile memories with the people around him was overwhelming.

Shortly after the book party, Dorine Starink told me that she and her brothers traveled to Paris to look at the places where, according to my research, their father had lived and worked as a resister. He had written a memoir for his family, but it needed the context of my book to come alive. Following in his footsteps with pride and a fuller understanding of his wartime adventures, Starink said, drew the siblings closer together.

Most poignantly, the book helped two unrelated people come to terms with the war.

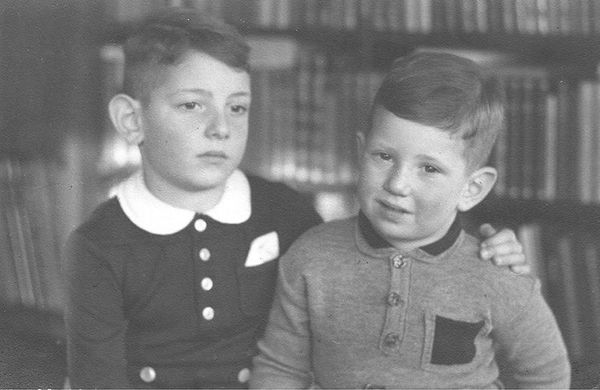

In January 1944 a young Dutch woman made a clandestine trip to occupied Holland on behalf of Dutch-Paris. When she left, Suzy Kraay took two little Jewish boys and their parents with her all the way through Belgium and France to the Swiss border. After a few weeks had passed, French police arrested her at a Paris café. Three days later, they turned her over to the Germans, who tortured the 22-year-old and threatened her family. After days of torment and fear for her parents, she broke down and did what she herself would find unforgivable: She answered her captors’ questions. Because they were extremely good at their jobs, the German interrogators used those clues to orchestrate a series of raids on many addresses in Dutch-Paris’ aviator-escape line.

Kraay survived the torture and a year at Ravensbrück. When she returned to the Netherlands in 1945, she took responsibility for the raids, even though she had given the Germans only the first pieces of information they needed. She married unhappily, moved away and refused to acknowledge her identity. At some point she returned to Amsterdam, but her children had no idea she had done anything the least bit unusual during the war. Needless to say, she did not attend the book launch.

Like many others, the brothers Reinold and Marcel Simon did not attend the book launch simply because we did not know how to contact them. Soon after the event, a neighbor asked

Reinold if he knew his name was in a new book. Several days later, someone else mentioned the same thing.

When Reinold read Gewone Helden, he learned the story of how his own family had come to be rescued, as well as the route they had taken from the Netherlands to Switzerland. All his parents had ever told him and his brother was that they had been rescued by the “Weidner group,” meaning Dutch-Paris. Other than that, they never spoke about the war, only about the happy times they had spent among friends as refugees in Geneva.

Now the Simons wanted to thank the woman who had guided them to safety. The message reached Maarten Eliasar, who knew who Kraay was — despite her denials — and even where she lived in his neighborhood. Eliasar arranged for the former resistance guide and the men she’d saved to have tea together. Kraay and the Simons became friends over a shared connection to a past that they had not spoken about but had haunted them for decades. Reinold’s wife, a retired psychotherapist, told Eliasar that her husband is a changed man — and all on the side of happiness.

Kraay also invited Eliasar over to answer questions about Dutch-Paris. Like so many others, she knew only what she had witnessed. My book explained what had happened to her as part of the line. The Simons reminded her of what she had accomplished as a resister. Now she could see past the horror of the Gestapo torture house to the good she had done. And her children discovered that their mother had served in the resistance.

As the history of Dutch-Paris makes its slow way out into the world through my book and talks, more Children of Dutch-Paris have found me. Some simply want to make themselves known. Others have stories or photos to share. They are all grateful, or relieved, to understand this context of their family lives.

As Americans we tend to think of World War II as a self-contained episode set squarely in the past. We were the good guys; our “greatest generation” won the war. It’s over.

Europeans, especially the Dutch, have no such delusions.

Indeed, the Dutch celebrate their liberation every five years with a big party. But every single year on May 4, the eve of their official Liberation Day, they remember their losses. I once stood in a line with thousands of Dutch men, women and children as they waited for hours without fidgeting or complaining in order to walk silently past a monument to resisters who were executed on the dunes outside The Hague 66 years earlier.

For most Europeans, the war was not battle but occupation. For civilians, occupation meant a constant struggle to survive morally as well as physically. The deprivation, compromises and anxieties of occupation molded every person who made it through the war.

The Children of Dutch-Paris have taught me that wars do not end when the weapons are stilled or the treaties are signed. They do not end even when the rubble is cleared and the last building is reconstructed. This is why World War I monuments still anchor every French village with the gravity of the community’s losses. These monuments list the local soldiers killed in the trenches, every name shadowed by the parents, siblings, wives, children and friends whose lives were scarred by that battlefield death.

Maybe a war ends when the last child stops suffering because of it. But when does that happen? The third generation? The fourth? How do we know when the memories of war cease actively shaping the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those who lived through them?

As a historian, I never expected my work to bring healing to families. If it also helps others to understand the realities of war and occupation, I have done well.

Megan Koreman is a historian and author of The Expectation of Justice: France, 1944-1946 (Duke University Press, 1999) and The Escape Line: How the Ordinary Heroes of Dutch-Paris Resisted the Nazi Occupation of Western Europe (Oxford University Press, 2018). More at dutchparisblog.com.