When I was in high school, I decided that because on the one hand there wasn’t anything else that I could possibly think of doing for a living, and on the other I needed to find a way to be beloved and famous without ever having to do anything dreary like make a living, I’d be a writer. So that’s what I did, and I kept doing and doing and doing until, bit by bit, when people asked me, “What do you do?” I could say something other than, at first, “I change diapers,” and then, “a lot of carpool,” and finally, “I sit in front of a computer all day trying not to slit my wrists.” One oughtn’t make jokes about suicide, but I figured that because joking about it is better than doing it, it was OK if I allowed myself various permutations of suicide metaphors when describing how I spend most of my waking hours.

And that’s because, at least in part, writing is so central to my very being that when I can’t do it, when the words don’t flow and, instead of walking away, I write endless amounts of pretty, puffed-up, poetic bullshit, I feel like my soul is dying. Also, suicide for me isn’t really an abstraction so much as a phantom, something I can sense but never really catch hold of from the corner of my eye. As a kid, I spent a lot of time thinking about it, both for its efficacy in ending my own misery and as a giant eff-you to my family, in keeping with my adolescent narcissism. Instead of ingesting a bottle of aspirin, though, I got help, which in turn provided me with enough ballast to pursue my dreams, such that by the time, in the summer of 2014, when my brother remarked that at times he was so down that he understood the attraction of suicide, I’d long since attained enough common sense to simply listen.

My two sisters, my father and I (my mother died of cancer in 2004) spend a lot of time discussing my brother: Why has he, among my parents’ four children, been so desperately plagued? What kind of demons drive him? I don’t know, but I do know about my own multifarious demons, and while I readily take my place among the highly functional female contingent of the sibling group, I know it’s a lie, a fib, a con. I can walk and chew gum at the same time with the best of them, but I do it on quicksand. One wrong footfall, one wrong shadow falling across my path, and that’s it: Like my brother, I’m consumed.

Sooner or later, though, I claw my way out. Usually with words. I sit in front of my computer and write. When the words don’t come, I feel abandoned. When they do, it all melts away: the roaring anxiety, my sense of inadequacy, my conviction that I’m not and never will be good enough, my terror of insignificance, and my fear of having been made wrong from the get-go simply vanish. Writing is what psychotherapists call my “safe space,” a place I go where the demons of my fraught childhood can’t follow. I have other safe spaces, too — my garden, for example — but nothing brings me peace like writing does when it’s going well. When that happens, it’s like I’m taking dictation from God.

Still, I’m pretty sure that, though he may not have me in the palm of his hand, it’s God and not me who’s in charge.

Speaking of God, he is, and always has been, a major player in my life. The two of us, we have a relationship, or at least I think we do. He can be pretty quiet, but I chatter on and on. Who’s to say whether he’s listening or not? (I don’t think God has a gender, but like many Jews I have been raised with a tradition that refers to the Divine in the masculine singular, and I will continue to do that in this essay).

Still, I’m pretty sure that, though he may not have me in the palm of his hand, it’s God and not me who’s in charge. What’s more, both my intuitions and the leanings of my heart tell me that my best shot at making a life that adds up to more than a string of days punctuated by events is to cleave to him as best I can, to lay myself at his mercy, to ask to be worthy of his love, and, most of all, to open myself up to his guidance. The way I see it is that God probably doesn’t much care whether I manage to lose a little weight. But he might just care a good deal about how I treat my loved ones, including my dogs.

This is all a back way into saying that, though I can’t imagine what my life would be without my pressing need to write and the satisfactions writing often brings, I also believe in the willful and nonadult part of me that still clings to the delusion that if I can just do it better — win the footrace, get the trophy, graduate summa cum laude, get the big promotion, be asked to be the keynote speaker — the family that I grew up in will see me for who I am and love me for it. Instead of being the family malcontent (my long-term role), I’ll be celebrated as a truth-teller, a seer, a person of great depth and moral sensitivities.

What this translates into is that I tend to feel like a failure except when I have a current (today!) byline or, better yet, book. If a publication includes the words “by Jennifer Moses,” I am, for the time being, fully alive. How do I know? Because it says so, right there in the newspaper — see? My name, in bold print. In 12-step circles this delusion is called “trying to fill a God-shaped hole” — the aching void, the gaping soul-wound — with something other than God. For addicts and alcoholics, it’s drugs and booze; for sex addicts, sex; for shopaholics — well, you get the idea. For me, it’s bylines, a product I don’t really have much control over, particularly since I haven’t had a regular job since 1989, the year I gave birth to our eldest son and quit my job at Bon Appétit, where I indeed did have a monthly byline, albeit for a column that amounted to no more than regional advertising copy.

That said, in the years since my days as an underling at Bon Appétit, I’ve published dozens of short stories, essays, criticism, opinion pieces and travel stories, as well as a bunch of books. (According to Google, I’m a “multigenre author.”) This at least is the stuff on my CV. I’ve also gotten gallons of rejections, so many rejections, in so many forms, including in 1981 from the then-famous Radcliffe Publishing Course and another that same year from several MFA programs, that I could wallpaper Versailles with them. That’s the stuff on my reverse CV, the one that exists only in my memory and is many times longer than the one I show people. And the rejections, the endless variations of “not for me, I’m afraid,” the doors slamming in my face: Even now, each one is a freshly brutal wound.

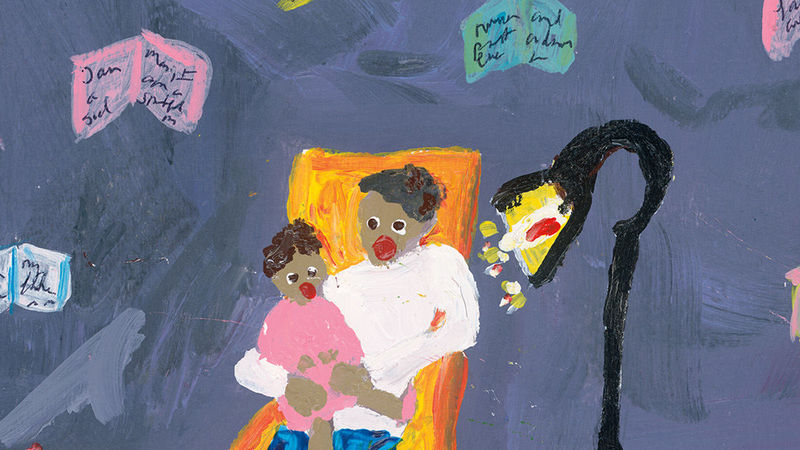

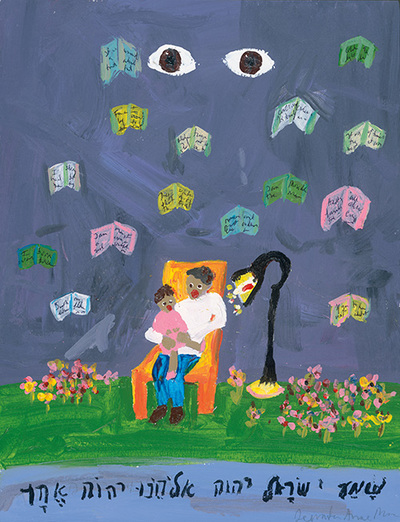

Hebrew text in artwork: ‘Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one.’ By Jennifer Anne Moses

Hebrew text in artwork: ‘Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one.’ By Jennifer Anne Moses

My husband is a professor of law who spends much of his own brain power writing his own books — which, unlike mine, have to do with the niceties and complexities of legal systems and the philosophical principles that underlie them. They’re scholarly works that treat inconsistencies in the legal system as philosophical problems in need of philosophical repair, and are read mostly by scholars, discussed on scholarly panels and argued over at scholarly conferences. He works from his brain, following one conundrum and its offspring to their logical ends, examining each section along the way with a Talmudist’s precision. Me, I write from my stomach. Or rather, it’s as if my brain is located in my stomach: it’s all hunches and associations and great leaps of inner music. Even so, each of us is a writer, and we frequently reference what we cornily call “the agony and the ecstasy” of our twinned pursuits, agreeing that there’s far more of the former than the latter. What are you working on?

We have, each of us and together, the ingredients of an almost ravishingly ideal life, including three now-grown children (and a daughter-in-law, courtesy of our eldest), two dogs, enough money to go to as many Broadway shows as we like, good health, fast metabolisms, a shared love of reading, scores of friends, a 100-year-old Arts and Crafts home in leafy, suburban New Jersey filled with an assortment of antique quilts, Oriental rugs, squishy sofas and, of course, piles of books. We have what almost no one else in our extended families and extended circles of friends has: control over our time. (Me more than my husband, of course, as he has to teach his classes, sit on committees, grade exams and so forth.)

Sometimes I look around and think that I’m living inside a New York Times lifestyles-of-the-fabulous-and-trendy spread. But I’m not living inside a home-fashion fantasy, and even if I were, behind the impress upon the retina that our collection of pretty things makes, I churn. I churn and burn and lie on the bed gripped by anxiety — and though I don’t go down the road to self-destruction in any tangible way, my brain, on fire, goes into its ritual, anti-self, anti-life anti-prayer: poseur, fake, third-rate hack.

Not always. Not even most of the time. The intonation, it comes and goes, and though it was more present than absent during the 20-plus years I spent raising my children as a stay-at-home mom, I managed to push the voices aside enough to be a reliable source of comfort, nurturance, rule-setting and love for the kids, or at least that’s what it seems like now, when they’re all postcollege and in the midst of launching themselves into their own future adult lives.

This is the good news, the news I cling to when I’m feeling particularly wretched, particularly in thrall to the chorus of who do you think you are? — when I’m convinced to my bones that the only way up and out of my utter nihility is by rising to the ranks of Shakespeare, of Moses, of Einstein or even of the late, great James Gandolfini.

The bad news is that I also cling to the desire to be among the genius ranks, my name, bathed in golden light, beloved. It’s not just 12-step programs that point out the delusional thinking behind my delusional conviction. It’s every faith path, every friend, every pond frond, every frog, The Book of Lamentations, The Book of Ecclesiastes, Woody Allen: “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work; I want to achieve immortality through not dying.” Every therapist, rabbi, teacher or, for that matter, priest I’ve ever consulted has told me that in the end, even Shakespeare ended up where we all end up, food for the worms, future trees, bits of recombined atoms floating in the infinity of the infinite. In the meantime, how to live? Which is to say, how to be alive while I’m still living?

Shabbat — the Jewish Sabbath, observed from sundown on Friday night to sundown on Saturday — is the worst day of the week for me. “Shabbat shalom!” I heartily say when I make my weekly call to my elderly father, who celebrates the day the way he always has, with a meal followed by his requisite eight-solid-hours followed by shul, in his case the Orthodox synagogue in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C., that he’s attended for more than 60 years. For a long time, I thought I hated Shabbat because it reminded me of all the things I hated about my childhood, including how my brother, being the only boy, was singled out, chosen, the rightful heir of the entire Judaic estate. In the decades since, my father and I have closed the old gap, and indeed one of the places we’ve landed, together, is in the Jewish way of being in the world, what my father refers to as “Jewish civilization,” which is not a civilization built in stone or studded with the remnants of a glorious past, but rather the millennia-long collection of shared history, belief, superstition, folk culture, high culture, philosophy, theology, mythmaking, prayer, ritual, food, music, literature, memory, language and, since 1948, haaretz — the land of Israel. Shabbat shalom!

Ah, the Sabbath day, with its clear-cut fourth commandment: “Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work; but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord God; in it you shall not do any work, you, or your son, or your daughter.” It goes on from there, but the message is clear: Cut it out. Everything that is non-God- or non-rest-oriented is a no-no. Prayer is OK. Reading is permissible. Taking a walk, with or without the dogs, why not? And with help from my rabbi, I do in fact bend all kinds of rules. Is gardening OK if, for me, it’s meditative? How about playing the piano? I’m working on a Bach prelude; like all Bach, it’s dedicated to God — is that OK? How about dancing? My very devout, very traditional rabbi has given me a pass, albeit it a soft one, for much of this, but I haven’t asked him about writing, because I know what he would say. He’d say no. He’d say that writing is my workaday work. He’d say: The seventh day shall be a Sabbath to the LORD. Only he’d say it in Hebrew.

But what if the writing that comes through me, when it does come through me, is a Sabbath to the Lord? If all those words pulsing through my innards and out through my hands somehow represent my small place in God’s great chorus and a gift that God has bestowed on me with the understanding that I am not to keep it wrapped up and shoved in a corner of my T-shirt and shorts drawer?

After they married, my father and mother settled in McLean, Virginia — then a semirural and extremely non-Jewish suburb, where they raised their children. For most of his career, my father practiced law in Washington. But his interests and expertise eventually took him into a variety of inside-the-Beltway jobs, including a stint as one of Jimmy Carter’s advisors and lawyers and another as Bill Clinton’s ambassador to Romania.

My two sisters have likewise made their careers in the law: my older sister as a partner at her New York law firm until, in 2015, she was appointed as a federal magistrate judge; my younger sister as in-house counsel at a multinational company. Both are graduates of Ivy League law schools. Or, as our father puts it, “Your sisters are superstars.” On my father’s side, the entire large, extended family boasts similar success stories, primarily in law and business, but also in academia and the work of bettering the world by protecting the planet from the vast degradations of human progress. Other than myself, no one — neither on my father’s side nor on my mother’s much funkier, much more flexible and less driven side — is a writer. To me go the bylines. To me goes the agony and the ecstasy.

So it was not without a certain amount of grim humor that I heard, from my father, that he planned to write a memoir of his years in Bucharest, and while he was at it, would I help him? I begged off. What do I know about the sticky business of being the ambassador to a small Eastern European country with a history of Stalinism, anti-Semitism and widespread corruption? Also, are you shitting me? After all my years of fighting off the urge to swallow gasoline as I struggled and prayed and suffered stomachaches at the hands of my overwhelming, life-giving and life-sucking need to write, to make something of myself, to say I’m here, I matter, my elderly father, whose way of understanding and processing the world is so different from mine that we may as well be members of different species, who had already enjoyed a kick-ass, inside-the-Beltway career, and for whom I’m still performing, hoping to at last (and on the brink of my own golden years) earn his two-thumbs-up, wants me to help him write a book about his diplomatic experiences in a tiny landlocked country tucked underneath Ukraine and above Bulgaria? What am I, chopped liver?

“Sorry, Dad,” I said.

Every therapist, rabbi, teacher or, for that matter, priest I’ve ever consulted has told me that in the end, even Shakespeare ended up where we all end up, food for worms, future trees, bits of recombined atoms floating in the infinity of the infinite. In the meantime, how to live? Which is to say, how to be alive while I’m still living?

Given how hard it is to write anything, let alone an entire book, I kind of doubted that he’d pull it off, but he persisted. He persisted so much that he not only wrote the book, but just like that, he got it published. And then, it happened: the book in the world, followed by readings and appearances, including various talks at various Jewish institutions, capped off by one at Washington’s historic Sixth and I Synagogue, where he was joined on stage by Senator Chris Van Hollen of Maryland, who did the Qs for my father’s As in front of a large, paying audience.

Truth in advertising: I, too, have appeared at the Sixth and I. We have a family connection there. But no one has ever paid to hear me talk. Likewise, the audiences I’ve drawn have not been what anyone would call large. Various D.C.-based friends of mine called or emailed to tell me how great my dad was, how funny and with-it and articulate and insightful. Why shouldn’t he be? After all, he was not yet 90.

My father’s book is called Bucharest Diary: Romania’s Journey from Darkness to Light, and it recounts his experiences as ambassador there, many of which were familiar to me from years of conversation. In my narrow role of reader, there were no surprises. In my bigger role, as daughter, and as one of the moving parts in a complex, big and self-regarding family — an elite club of “we” all unto ourselves! — things were more complicated. But then again, aren’t they always?

My father called recently and said: “I don’t know, Jen, I have no experience with this. But people tell me the book is good, but what do I know about these things? I’m speaking next week in Tel Aviv.”

“Tel Aviv?”

“At the Museum of the Jewish People. Is that good?”

I assured him it was. Afterward my husband’s brother, a journalist who has lived in Israel for more than 30 years and attended the event, emailed to tell me that my dad had drawn a large audience composed of the crème de la crème of Israeli society — journalists, diplomats, businesspeople, government officials — and that he’d been astonishing. “He spoke without notes,” my brother-in-law wrote. “He remembers everything, every last date and detail. He knows his European history back and forth. We were blown away.”

When he returned from Israel, my father told me that he had another six or seven speaking engagements lined up for the book. “Who knows?” he said. “It may even sell.”

My go-to response, whenever confronted by a friend or relative’s or classmate’s or acquaintance’s success, particularly when such success occurs in my own avocational sliver, is envy spiced with the under-tang of resentment. In the case of my father and his book and his lectures and his fans, though, what I mainly felt was: Good one, God! As everyone knows, God has a sense of humor. I mean, why shouldn’t my then-nearly-90-year-old father go on a book tour? Why shouldn’t he (and not I) have a Wikipedia page and a bunch of honorary degrees and genes so robust that if anyone gets Woody Allen’s wish to become immortal through not having to die, it may well be my father?

My father is not immune to sorrow. He lost my mother. Most of his lifelong pals are gone. His own generation of siblings and cousins is rapidly disappearing. But not for him was a cancer like the one that killed my mother or the one that visited me for a year 15 years ago or the one that twice paid a brief call on my older sister. Not for him the howls into the unhearing and vast nightmare world the mentally ill inhabit, or the serial marriages of the romantically unlucky, or the everyday misery of economic uncertainty, or the anxiety that on occasion swallows my brother whole, or what I myself suffer from, that vast curdling gap in my guts and soul, the “God-shaped” hole I keep trying to fill with bylines.

What does one do with a family backstory like mine, so bright and successful on the outside, so afflicted with ordinary, inescapable human pain and imperfection elsewhere, all of it sealed in an impenetrable cone of silence? What does one do with one’s endless, unquenchable yearning? I read, I swim, I garden, I play the piano, I walk the dogs, I talk to my husband, I talk to my friends, I talk to my rabbi, I talk to the sky, but most of all, most of all, I talk to God, the author of all. Because I know that when my father really does die, as he like all mortals must, my grief will be so vast that only God will be able to bear it.

Jennifer Anne Moses is the author of six books, including Visiting Hours, a novel in stories, and The Art of Dumpster Diving, a novel which will appear in March 2020. Her essays, short stories and opinion pieces have been widely published. Find her at www.jenniferannemosesarts.com.