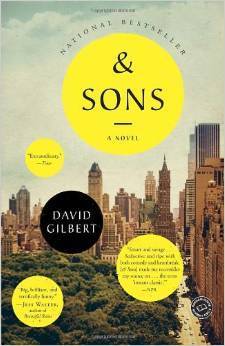

It’s a book title I have to explain when talking about & Sons by David Gilbert. It’s the ampersand. Not exactly “and” sons. And pretty vague about what precedes the sons, what the sons are attached to.

But this is a very fine novel that explores the deep, complicated and mysteriously threaded entanglements between fathers and sons. I sought it off the library shelf because it was named to a list of top fiction books of 2013 and because I am drawn to examinations of father-son dynamics.

The father in the text is a reclusive but celebrated author named A.N. Dyer who dedicated his life to writing books, not to his family. In a lifetime of literary achievement his early work Ampersand (partial ah-hah to that &) has long stood as a classic. Set in an elite East Coast private school, the story which explores teenage angst has been popular with generations of young readers and championed by literati. And yet its creator, despite further works of merit and an affectionate following, has retreated more deeply into himself, into his haunts, and has failed his wife and two older sons.

The book is their story, too — a tale of the broken parts that remain when children miss out on affection and parental affirmation.

While some critics suggest Dyer as a J.D. Salinger type, the themes are more broadly universal. We can all think of people who have succeeded in the public arena or professionally or who have altruistically devoted themselves to causes outside the home who have not succeeded as family members, as parents, or as human beings.

The author’s desire late in life to redeem himself with a third son, a special son — and one who does not share the same mother as the two elder sons — gives the novel a twist and an avenue for further examining favoritism and sibling rivalry.

Interestingly, the narrator is the son of Dyer’s lifelong friend, who yearns to be folded into the Dyer clan (with ambivalent feelings about his own father) and through whose eyes the narrative unfolds. The story is so well told and so masterfully written that you just might forget to question how the narrator reports on moments and conversations he was not present for.

The characters are real and flawed and finely drawn, the family dynamics true and incisive. The story telling and scene setting are engaging, sometimes captivating. The whole novel is wonderfully written, with sentences and moments smartly layered and richly meaningful.

Here’s one, Gilbert’s narrator speaking of his own father:

“At some point between the swimming and the exploring of dunes and the tossing of various discs and balls, I would gravitate to the doldrums, hoping for sympathy. My dad was always quiet yet genial, like a foreigner who could only respond with a few common expressions. By the age of twelve I had pretty much given up on him and even told my mother so in a moment rife I’m sure with Freudian overtones. ‘I don’t really love him,’ I said. She looked at me as if I had handed her something homemade and easily broken. ‘That’s okay,’ she told me, touching the back of my head. ‘You will someday.’”

Kerry Temple is the editor of this magazine.