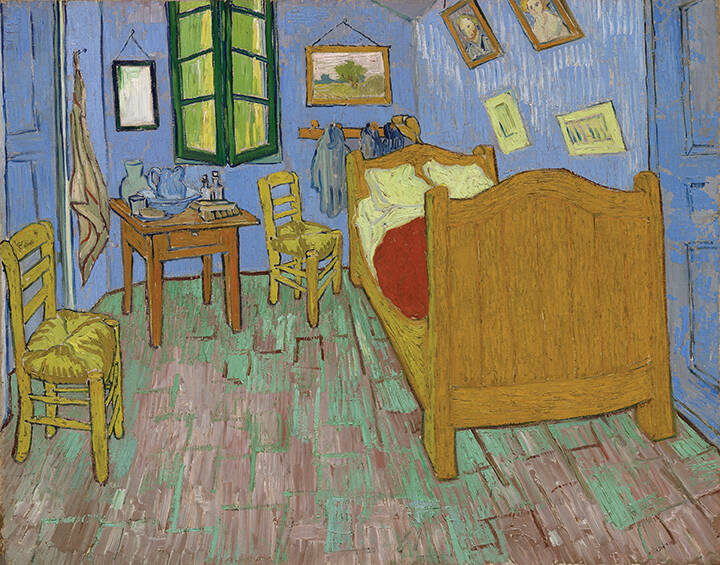

Vincent van Gogh, The Bedroom, 1889, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection, Chicago Art Institute

Vincent van Gogh, The Bedroom, 1889, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection, Chicago Art Institute

In the spring of 1890, Vincent van Gogh fled the busy, intense life of Paris. He wrote his friend, Paul Gauguin: “The noise . . . of Paris had such a bad effect on me that I thought it wise for my head’s sake to flee to the country.” Van Gogh settled in Auvers-sur-Oise, a simple village of several thousand people. Shops, cafés and quaint houses, many with window boxes filled with geraniums, lined the narrow streets.

In letters to his brother, Theo, the struggling artist wrote: “Here one is far enough from Paris for it to be the real country,” and “Auvers is very beautiful, among other things many old thatched roofs, which are getting rare. . . . Really it is profoundly beautiful . . . characteristic and picturesque.”

During those final months of his tormented life, van Gogh rented a small room at the Ravoux Inn. Over time, after one of the world’s most celebrated artists died in the obscurity of this drab space, the hotel fell into disrepair, just as the fame of its former lodger continued to rise.

Several decades ago, a Monsieur Janssens was in an auto accident directly in front of the defunct hotel. While recovering, he read a history of the place. Then he bought it. He carefully restored the building as it was when van Gogh lived and died there at age 37. Janssens converted the little hotel into a museum that began to attract visitors from all over Europe.

I read the story of how this new museum came to be. I wrote to Janssens, who thought I was a famous American writer. When I arrived in Auvers in early 1995, I went directly to the museum. Janssens graciously closed the facility for 20 minutes so I could sit alone in the room where van Gogh died.

Entering the room I was filled with emotion. As I looked around, I experienced a shortness of breath and felt on the verge of tears. It was as if I had somehow mystically connected with the struggles that took place here inside van Gogh’s heart and head, and I became deeply saddened. I was struck by the irony of such an unpretentious room housing such an immense artistic spirit. I imagined how some of his biggest and best canvases sat unceremoniously in the corner or under the bed, their creator unaware that someday they would grace the world’s finest museums, attracting art lovers from around the globe. The room looked more like the cell of an anonymous monk, not the last home of a world-renowned artist.

Van Gogh moved into the hotel on May 20, 1890, paying three and a half francs per day. Every morning, he left the inn to paint in locations around Auvers, not returning until dusk. For two months he bravely battled his demons and painted with amazing lucidity and speed. He almost survived. Almost.

Suffering spiritual and mental anguish, van Gogh either shot himself with a small pistol or, as a recent controversial theory suggests, was shot accidentally by mischievous teenagers who were taunting him for his eccentric behavior. He wasn’t killed, but the bullet lodged so deeply in his chest that an infection set in. Two days later, on July 29, he died, lying in that dull, dreary room in pain and thinking himself an utter failure. But Theo was there. Vincent knew his brother’s love, and it must have comforted him, must have made his sad, slow slide into immortality a little easier. At least he wasn’t alone.

He still is not alone. A little over a century later, for instance, a writer born in Brooklyn, New York, who lived and worked in Hollywood, bedeviled by his own demons and searching for his own answers, visited the room and was deeply moved by van Gogh’s life, his struggles, his art.

The room was empty save for a small wooden chair with a straw seat that occupied a corner. I sat on it. I grabbed my notebook and jotted down my impressions:

It’s the humblest of tabernacles, housing a living presence that still has the power to inspire 105 years after the actual lifeless body was removed. . . . It’s an empty space, a quiet space. And a very small space. I counted eleven steps from the entrance to the back wall; from side to side, only ten steps. The floor is unvarnished wood: plain, worn. The walls are plastered two-tone: off-white on top, and an indistinguishable darker, lifeless color on the bottom. Part of the ceiling slopes, making the room feel even smaller. One tiny window, perhaps two feet by two feet, looks up rather than out because it is located on the slanted part of the ceiling. It lets in a little light, but offers no view of Auvers-sur-Oise.

Visions of the peaceful, little village were in Vincent’s head, his heart, his very soul. And they were visions only he had, but, fortunately, the artist was eager to share them with us. He produced 70 paintings in 70 days. He infused the little houses and narrow, winding streets of Auvers, along with some of the residents, the church of Notre Dame, and the wheat fields that encircle the village with his own colorful, imaginative vision of their reality. A vision that still haunts and inspires us over a century later.

Vincent died in this dingy room, in this cramped space, but he still lives here. He’s not in Arles or St. Remy or Amsterdam or even in any of the many museums around the world that house his masterpieces and hawk postcard duplicates of their treasures. Vincent is in Auvers-sur-Oise, in a little, unadorned, humble, empty attic room with no view, located just a short walk from the wheat fields that gave him deep but temporary comfort, just a short walk from where he is buried next to his beloved brother, Theo. Peaceful at last.

I closed my notebook, stood up, took a deep breath, and looked around the room one last time. The night before, I had read the letters Vincent wrote to Theo during his time in Auvers. A few lines from the letters reverberated through my mind: “I still love art and life very much” . . . “but my life is also threatened at the very root, and my steps are also wavering” . . . “but knowing exactly what I wanted, I have painted three more big canvases.” . . . “They are vast fields of wheat under troubled skies, and I did not need to go out of my way to express sadness and extreme loneliness.” . . . “Well, the truth is, we can only make our pictures speak.”

Van Gogh’s voice may have been silenced, but his art still speaks loudly and eloquently. I turned and left the room and headed for the wheat fields and Vincent’s grave, walking past Daubigny’s garden and the church of Notre Dame.

As I traversed the fields that encircle Auvers-sur-Oise, I felt as if I had been there before. In a way I had been, years earlier, during a trip to Pittsburgh of all places. The only thing I really wanted to see in the Steel City was the Carnegie Museum of Art. I had heard the museum had a decent collection of French Impressionist paintings, and I was hoping it included something from van Gogh’s oeuvre. As soon as I entered the largest exhibit hall, I immediately spotted on the far wall a van Gogh painting. I went directly to it, not bothering to look at paintings by Monet and other great artists.

Never before had I been so affected by a work of art. The painting was titled Wheat Fields after the Rain (The Plain of Auvers). It was certainly one of van Gogh’s last works. It is difficult to put into words what I felt, as I stood in front of this painting, transfixed by its simplicity, harmony and emotion. I don’t like using the words “mystical” or “transcendent” to describe what I experienced as I stared at van Gogh’s creation, but those words come closer to expressing what I felt than any other.

I can recall two occasions in my life when I felt the lightness of being outside my body, of having risen above the realm of the physical experiences of sight, sound, taste and touch, of being transported to a new dimension of understanding and insight. One such experience happened in 1976 in the Church of St. Paul the Apostle on the west side of Manhattan. Another occurred in 1985 in an Orthodox monastery in a small town in upstate New York. On both occasions I was convinced I had broken through the limits of my comprehension and discovered a new way of seeing things.

But standing before van Gogh’s Wheat Fields was the most mystical experience I have ever known. I felt extremes of joy and sorrow, of pleasure and pain, of peace and torment. I felt my hand on van Gogh’s paintbrush. I felt his anguish, his hope, his vision expressed by the colors on his palette. I felt the power of creation, which is really the power of God.

I looked and looked, and the more I looked, the more I saw. I cried. I smiled. I saw the thickness of his paint, the quickness with which he expressed the emotion he felt while looking at the field. I understood that this was far more than just a painting of a wheat field near Auvers that had been captured on a particular day in 1890, but was also a spiritual biography of van Gogh’s long struggle to understand life, to make sense of all he had seen, heard and felt. It was not just a painting of a wheat field; it was a statement about life.

Van Gogh found temporary solace and relief for his sadness, worry and anxiety in the calm of those wheat fields with their soft colors and boundless expanses. During the last month of his life, he painted many different versions of them. He wrote to Theo:

I am completely absorbed in the immense plain of wheat fields against the hills, boundless as the sea, delicate yellow, delicate soft green, the delicate violet of a dug-up and weeded piece of soil, checkered at regular intervals with the green flowering potato plants, everything under a sky of delicate blue, white, pink, violet tones. I am in a mood of almost too much calmness to paint this.

The calm did not last long. Van Gogh’s mood turned somber and hopeless, emotions he had vividly expressed under the dark and stormy skies of his famous canvas Wheatfield with Crows, a menacing painting that is laden with symbols of life rushing toward a dead end as it captures the sadness and the extreme loneliness van Gogh felt during the final days of his life.

As I stood alone in the Carnegie Museum of Art, I felt confident — for the first time after abandoning my career as a network television producer — that I could and would be a serious writer, and I realized how this one painting taught me more about writing with simplicity, clarity and euphony than any book or living teacher ever could.

Vincent van Gogh was buried on July 30, 1890. It was a hot afternoon. Paying homage to his friend, Dr. Paul Gachet spoke a few words: “He was an honest man and a great artist. He had only two aims, mankind and art.” Weeping, the doctor said, “Art he loved above everything, and it will make him live.”

Gerard Thomas Straub is the author of The Sun & Moon over Assisi, named the Best Spirituality Hardcover Book of the Year by the Catholic Press Association in 2001. He runs a home for abandoned children, Santa Chiara Children’s Center, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti: Visit santachiaracc.org.