Illustration by Blair Thornley

Illustration by Blair Thornley

I was sweeping out the garage last week when, for some reason, I noticed my father’s old tackle box sitting on the shelf above the dryer. The battered metal box was one of the few things I asked for when Dad died 15 years ago. I hadn’t given it much thought since then, moving it with me from house to house where it sat gathering dust, first in the attic and now on a garage shelf. But that morning, perhaps because the anniversary of my father’s death was only a few days away, I felt this relic calling to me.

I leaned my broom against the wall and took down the metal box, the handle rasping in my grip. I held the box in both hands for a moment, surprised by the tenderness welling up in me. Gunmetal gray and rusting at its hinges, it was scored from being dragged through the brush and bramble, scratched by rock and sand. I set it on the workbench and opened it up to look again at what it holds: tin plug tobacco cans where my father kept his split shot, a few brightly colored lures, the dirty stub of a candle, a small tangle of hooks, rusty nail clippers. Bit players in the magic he’d weave those nights out in the moonlight and mosquitoes when I was a little boy, no one else on the wide earth. The faint smell of fish and tobacco loosed a memory so clear it split my heart wide open.

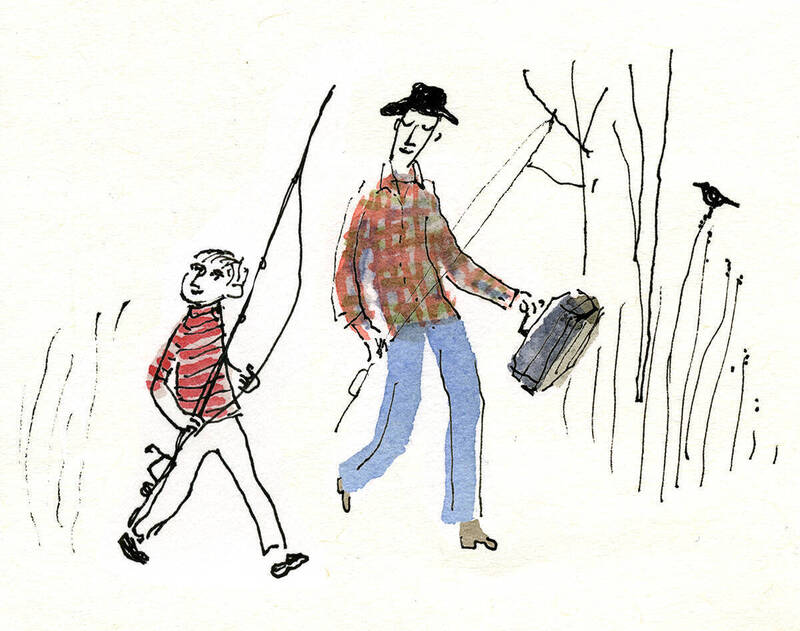

We are on a country road in northern Michigan, my father walking on one sandy track, me on the other. Carrying our fishing rods. Dad swings his battered tackle box in long, lazy arcs, keeping time with his stride. A red-winged blackbird swoops from fencepost to fencepost, pausing to trill his reedy song. The low evening sun sets the tall grass aglow in golden light. Crickets chirp their warning from the brush. Anticipation is running high on my side of the road.

I must have been 8 years old, and I considered myself a savvy fisherman, but I’d never been to Shell Lake where, according to family lore, the water teemed with smallmouth bass the length of my arm. Bluegill the size of small frying pans. Even the perch, those annoying sucker fish that waste your night crawlers, were big enough to eat at Shell Lake. And we were finally going.

The scene came to me whole as if cached away in the tackle box, waiting to be sprung. Later that night at the lake, I cast a weedless frog lure into some lily pads. I popped it along the surface and was watching it float in the full moon reflecting from the black water when a massive bass erupted from the surface and hit my line so hard it nearly yanked the rod from my hands. The drag screamed as the bass dove for deeper waters.

My father hollered, “Hold on, Boo! You’ve got him!” The rod was bent in half, every crank of the reel a struggle. I fought him for what felt like hours, pulling up on the rod and reeling in the slack over and over again, my father coaching me the whole time. When I finally hauled the fish up into the shallows, Dad ran knee-deep into the water, grabbed it by the mouth and hoisted its long body, scales glittering in the moonlight. I looked at my father, standing with a monster worthy of the wall of a bait shop. He lasered a look of pride at me. “You’re a winner, Boo,” he said, “always have been.”

What I wouldn’t give for one of those looks even now, I thought, as I picked the candle stub out of the box and considered it in the palm of my hand. That little boy had no idea what was coming.

When I was 13, my father was all but erased by a minor stroke one ordinary Sunday afternoon while taking a nap. I remember walking into the living room the day it happened, curtains drawn against the afternoon sun and Harry Caray calling the White Sox game on television. I expected to see Dad asleep on the couch, but he was sitting on the edge with his head in his hands. Was he crying? Mom was sitting beside him, rubbing his neck and saying, “It’s OK,” over and over. She gave me a get-out-of-here look, and I shuffled outside, wondering what strange netherworld I had stumbled into.

It was how I first learned to love him — watching him, seeking his attention, basking in his gaze when he looked my way.

The stroke went undiagnosed for years. He was still with us, going to work, mowing the lawn, smoking Viceroys and watching Walter Cronkite from his recliner, but he would often struggle to remember the simplest things. He’d get this lost, panicky look and interrupt my mom to ask her something he’d already asked moments before: What day was it? Where was my sister? Had he picked up his medicines at the drug store? Then he’d realize he’d forgotten again, hot shame stealing into his eyes, and he’d recede into a place where no one could follow. Over the months following the stroke I realized that he’d been hollowed out and was only a husk of that magnificent creature who once strode through my childhood.

I opened the tobacco tin and took out a couple of split shot, rattling them around like dice in my hand. A meteor had struck that afternoon when my father lay napping on the couch, and I’ve been living in the echoes of its blast ever since. I put the split shot back into their tin and shut the box, its old metal hinges groaning. I snapped the latch and found an oily cloth to wipe the box down.

After Dad’s stroke, the drinking ramped up, or that’s how I remember it. My mother and sisters have their own stories, and I have learned not to fully trust my memory. I was in my 20s when my parents called it quits — plenty old enough to take it in stride, or so I thought. But when the woman I loved left me soon after, it tore an outsized hole in me. I found my way to a therapist and spent my late 20s tweezing apart the threads of my fear and anger. Every strand led back to the loss of my father.

He never learned the names of my four children. Was he incapable, or could he simply not be bothered? I never knew. What I did know for sure was that I was on my own. I tried for years to lower my expectations of him, but I couldn’t stop hoping he’d help me navigate my life. That he’d take more of an interest in me. It was how I first learned to love him — watching him, seeking his attention, basking in his gaze when he looked my way. The stubborn little boy in me would never stop trying to find that version of love. I could no more stop needing him than I could stop needing oxygen.

I buffed up the tackle box as best I could and set it back on the shelf. With the box safely back in its place, I felt its power beginning to ebb. I was dazed, as if awakening from a fever dream. I grabbed my broom and got back to sweeping, surprised by the rawness of those memories and the fresh pain they could sear into me.

Yet maybe it wasn’t so surprising, I thought. The pain of losing my father is bleached into my bones, the ache shot through with a stubborn love. The golden light of those summers at the lake still shines. I closed my eyes and imagined the late afternoon sun on my face, running barefoot as a boy over the green grass behind my grandfather’s cottage, dodging and weaving with my sisters and cousins among the legs of towering adults. My parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles standing with highball glasses clinking in one hand, cigarettes smoldering in the other. Grasshoppers clicking in their short, heavy flights through the cooling air. Distant growl of a ski boat out on the lake. Laughter mixed with the hum of grown-up conversation.

Memories of Eden, the thrumming ache for paradise that will follow me all my days. They offer a promise that all things will be restored, all things renewed. Relationships made whole again. How I yearn for that. It’s not something I will forget, that holy evening so long ago when my father and I headed out for Shell Lake, walking side by side along sandy tracks, tall grass running down the middle, a red-winged blackbird trilling from his fencepost, the hot day giving itself over to a delicious cool.

Every last thing set right.

Bruce Lawrie lives in Scotts Valley, California. His work has appeared in Portland Magazine, The Best Spiritual Writing 2011, Fathom, U.S. Catholic, and elsewhere.