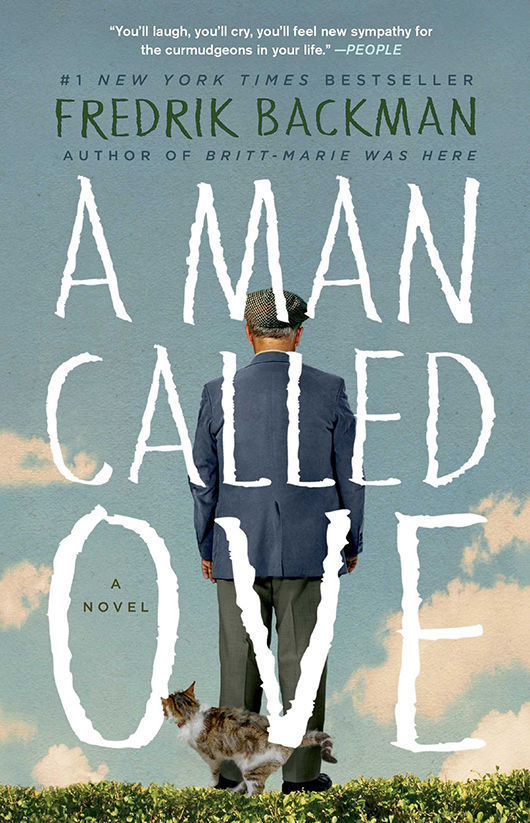

I disliked Ove even before I met him, the instant a neighbor placed Fredrik Backman’s internationally bestselling debut novel, A Man Called Ove, in my hand, gently insisting I should read the book and — even more infuriatingly! — insisting I would like it.

I had already turned this suggestion down once, but my neighbor ignored me, promising to deliver the book when he’d finished it. I’d walked home from that first offer certain I’d won the round, that he’d take the hint and my diplomatic deflection would be the end of it. I don’t take book recommendations. Yet there was the same neighbor a few days later, standing in my front hall, visiting on some other friendly pretext, smiling and holding out A Man Called Ove. Which, he repeated, was really terrific.

I’d exhausted my options. Alan has fixed my lawnmower more times than I’ll thank you to remember. He talks me off the ledge whenever my wide-ranging mechanical incompetence threatens to whisk me headlong toward neighborhood humiliation or self-harm. He deserves at least this courtesy, I decided, assuring myself that by giving his book a place to stay for a few weeks, I was doing him the favor.

Months later, when the novel showed no intention of falling off my nightstand and hiding behind the bed, I conceded to read one chapter.

Page one confirmed my prejudice. Ove, 59, recently retired and living alone in a Sweden that no longer seems to want him, is trying to buy a computer and making the sales staff miserable in the process. Surly, a perfectionist, impatient with novelty, he is contemptuous of everyone around him. He gives people nicknames drawn from traits he doesn’t like, rather than learning their names. He — at least in English translation — uses the adjective “bloody” to vent frustration, a Britishism that strikes me as out of place for a Swede. Why would I want to spend another 336 pages in his company?

But Chapter 1 (“A Man Called Ove Buys a Computer That Is Not a Computer”) is only four pages long. Not enough for a credible rejection. And then, in Chapter 2 (“. . . A Man Called Ove Makes His Neighborhood Inspection”), Ove lets his own fastidiousness and a knock on the door foil his first attempt at suicide.

Meddling neighbors. Oblivious impositions. Self-loathing at his own weak capitulations to others’ bloody demands. It seemed that if Ove and I could make a list of regular irritations, we’d find we have a lot in common. Except 1) I’m not suicidal; 2) my neighbors don't really meddle or impose; and 3) Ove knows his way around a toolbox.

For another 100 pages or so, I still hated Ove, the curmudgeonly cliché whose deathwish and prickly pigheadedness in the present I felt consistently undermined Backman’s skillful unfolding of Ove’s charming and sorrowful past, the backstory that turns this aging, pain-in-the-ass loner into a genuinely sympathetic character. Somehow, though, I couldn’t give up on Ove.

Neither can many of his neighbors. And the harder he tries to push them away, the more entangled he becomes in their lives.

There’s Parvaneh, the young Iranian immigrant whose hapless Swedish husband and late-term pregnancy and inability to drive ensnare Ove into multiple car trips to the hospital. There’s Adrian, the shy teenager who needs help fixing his bicycle, and Adrian’s friend Mirsad, terrified that his father will find out that he’s gay. And there’s Anita, whose husband Rune, now slipping into dementia, was once the closest thing Ove had to a friend — until life’s injustices and a hyper-masculine inability to communicate taught the two men that they were perhaps a little too similar.

Backman reveals his sense of humor and sensitivity to the deeper wounds within us most readily in his chapter headings. In Chapters 27 (“A Man Called Ove and a Driving Lesson”) and 28 (“A Man Who Was Ove and a Man Who Was Rune”) Ove reluctantly agrees to teach Parvaneh how to drive his manual-transmission Saab. As they lurch and jolt around parking lots and streets, Backman pushes deeper, measuring out the lives of Ove and Rune in the Saabs and Volvos they each buy over the years mostly in reaction to each other or to the tragic circumstances of their lives. And when Ove explodes in anger, rising to Parvaneh’s defense against an aggressive SUV driver with a shaved head and a neck tattoo, I realized suddenly how much I had come to like him. Backman seems to know this moment has come for the last of the anti-Ove holdouts like me. “So there were certainly people who thought that feelings could not be judged by looking at cars,” the episode concludes. “But they were wrong.”

I was wrong about Ove. And I was glad to be wrong, grateful to encounter a novelist who achieved in his first effort what all the best ones are able do — to better acquaint us with ourselves, to smile at our own limitations and see the world afresh through the power of a good story. Despite its deceptively light touch, A Man Called Ove reminds us of the dark power we have as human beings to force ourselves and each other into narratives that confine, diminish and ultimately imperil us in isolation and despair, and the obligation we have to pull one another back into the light.

I don’t think Alan was pulling me out of anything when he lent me Ove. I don’t think he had anything in mind other than the wish to share a good book and a laugh. Tomorrow I’ll give him his book back. I’ll have to fight off the temptation to tell him I couldn’t get into it. I may actually thank him for his persistence. It was a pretty neighborly thing to do.

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine. When he isn't being a prickly pighead, he actually does take book recommendations. Sometimes.