Abraham Lincoln confessed to a debate audience in 1858 that, in the mere half hour allotted to him for rebuttal, he could not possibly address all the points Stephen Douglas had raised in his 90-minute oration.

“I hope, therefore, if there be anything that he has said upon which you would like to hear something from me, but which I omit to comment upon, you will bear in mind that it would be expecting an impossibility for me to cover his whole ground,” Lincoln said.

In Amusing Ourselves to Death, Neil Postman writes, “It is hard to imagine the present occupant of the White House being capable of constructing such clauses in similar circumstances. And if he were, he would surely do so at the risk of burdening the comprehension or concentration of his audience.”

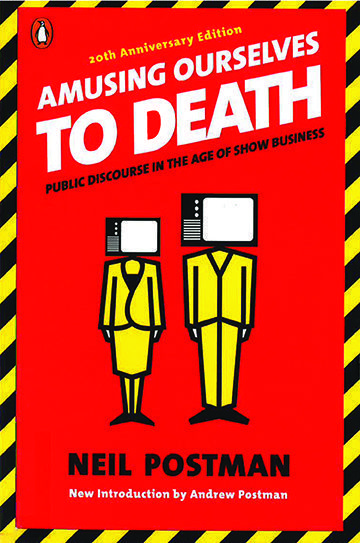

At the time Postman published his indictment of the technology-shriveled American attention span, the occupant of the White House was Ronald Reagan. The year was 1985 and the culprit was television, the perfected instrument of what Postman called the Age of Show Business.

That seems like a long time ago, technologically and politically speaking, but the insights in Postman’s book feel all the more acute and applicable now that Reagan, in retrospect, seems positively Lincoln-esque compared to many of today’s elected officials. Granted, nobody cites the Reagan-Bush debates from the 1980 Republican primary as a high point in American political discourse. “There you go again” and “Where’s the beef?” endure as the sound bites of that era.

Read the YouTube comments on this Reagan-Bush debate video, though, to discern a retrospective astonishment that the American electorate ever could have had it so good.

“Omg there’s so much much substance and class here. . . .” begins a commenter called Alice Aquarius.

Much much. OMG.

Postman, who died in 2003, no doubt would have much much to say about the impact of the internet in general, and social media in particular, in furthering the degradation from what, by the 1980s, already felt to him like a rhetorical rock bottom. In Amusing Ourselves to Death he palpably longs for the days of Lincoln-Douglas and for American audiences that could stand hours of that kind of thing. A separation of entertainment and state.

That wall, he writes, went down around the turn of the 20th century, when the diverting visuals of photography met the speed of the telegraph wire. Sensational news from far away could be delivered fast — and with pictures! The Age of Typography, as Postman dubs the literate era that showbiz came to overshadow, began to decline even then, with newspapers still ascendant but their journalism yellowing.

Entertainment not only began to be elevated over information, even when it came to issues of serious public importance, but the two also became indistinguishable. News as theater.

Not that information was in short supply. On the contrary, Postman argues, the telegraph inundated us with it — about everything from everywhere. But the demands of the format rewarded superficial breadth. “Implications, background, or connections” became irrelevant, he says, and historical context a telegraphic excess.

So fundamental was the impact of this technological change, it altered the definition of being informed. “Intelligence,” he writes, “meant knowing of lots of things, not knowing about them.”

Telegraph inventor Samuel Morse asked “What hath God wrought?” in the first wired message. Postman answers: “a neighborhood of strangers and pointless quantity; a world of fragments and discontinuities.” His assessment might be cut and pasted into a sentence about social media today.

By the time TV came along, in Postman’s telling, the collective intellectual damage had been done. The appeal of the moving images, the abrupt shifts from one topic to the next — “now this,” as he titles a chapter in broadcast-ese — buried us deeper in an avalanche or names and faces, places and incidents, about which we understood little of significance.

Everybody knew of the Iran hostage crisis of 1979-81, for example, an event that spawned its own TV show, Nightline. It’s hard to imagine the American media giving more sustained air time to a story or the public paying closer attention. Yet in his acerbic pessimism, Postman wonders, “Would it be an exaggeration to say that not one American in a hundred knows what language the Iranians speak? Or what the word ‘Ayatollah’ means or implies? Or knows any details of the tenets of Iranian religious beliefs? Or the main outlines of their political history? Or knows who the Shah was, and where he came from?”

The ignorance of which precluded few from opining as if well-informed, and those views themselves became their own news story — “53 percent of Americans say . . .” — a self-perpetuating cycle that Postman describes as “a great loop of impotence: the news elicits from you a variety of opinions about which you can do nothing except to offer them as more news, about which you can do nothing.”

That description sounds familiar — and concise enough to fit in a tweet. If the telegraph led to television and our diminishing capacity to accumulate knowledge before emitting opinions, what have Facebook and Twitter made of us? A nation of Abe Simpsons (that passes for a common cultural reference, right?) shaking our fists at clouds.

Postman’s most poignant and pointed conclusion is that we did this to ourselves. He wrote Amusing Ourselves to Death at a time when we were of a mind to evaluate how Orwellian our world had become, how much 1984 resembled Nineteen Eighty-Four. Not so much, Postman determines. At least not in the United States.

We are heirs instead to Aldous Huxley and A Brave New World, he writes. The tools of oppression have not been imposed by an autocratic state, as Orwell’s dystopian vision envisioned. Instead, we binge on our TVs and smartphones, the equivalent of the soma that anaesthetized Huxley’s citizens into pleasurable passivity.

“As (Huxley) saw it,” Postman writes, “people will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think.”

When I look away from my phone long enough to consider it, Postman’s critique seems all too prescient, although the technologies we turn to today have become so embedded that their use now feels less like adoration than addiction. We want to delete Facebook and deny the access we have granted the public to our digital DNA, but we don’t. On Twitter, people constantly tweet about how terrible Twitter is, a take that’s always good for a few retweets. Speaking of “a great loop of impotence.”

On guard against the imposition of tyranny, perhaps on a Cold War footing, we did not take into account that tyranny could come from within, through what Huxley called our “almost infinite appetite for distractions.” Whatever the medium of the moment, we tune in to tune out.

“Big Brother,” Postman writes, “turns out to be Howdy Doody.”

The reference might be dated, but the sentiment has lost none of its currency. You could make it into a meme and post it.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.