On the first day of her class my sophomore year, creative writing professor Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi asked us to take a walk. In pairs, we slipped out of DeBartolo and onto the quad. We considered the rhythm of our movement. We pondered the capacity of spaces to store memory. We contemplated how walking deliberately might inform our thinking and our writing.

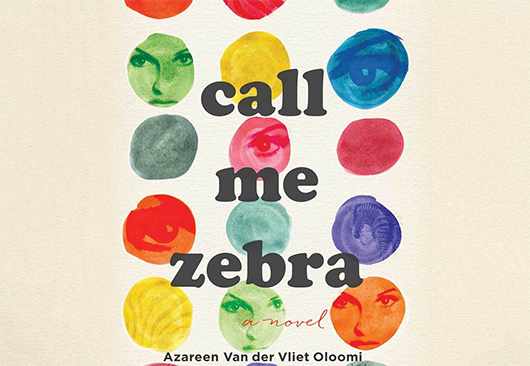

In Call Me Zebra, her much-anticipated second novel, Van der Vliet Oloomi expands on these ideas. Her obsessive and eccentric narrator, Zebra — a name she gives herself — sets out to retrace the path of her family’s exile from Iran in reverse, writing her own manifesto as she travels. This “grand tour of exile” leads her from New York through the Mediterranean and toward the country of her birth.

Zebra’s meditative walking is a means for her to grapple with her tumultuous past, which started when the family fled from their home during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s. She hopes to honor their story by revisiting both the spaces her family once occupied and the books they devoured and cherished. As she travels, she studies the living, growing “matrix of literature” that connects her to her ancestors.

Introspective, Zebra was raised with books — literally. She was born in the family library, where she spent much of her free time growing up, committing the greatest works to memory. Her dialogue is rife with quotes from and allusions to Dostoevsky, Goethe, Cervantes and Dante.

On this “literary pilgrimage into the void of exile,” Zebra uses literature as a map. For her, “landscape and literature are entwined like a helix of DNA.” But on her journey, Zebra learns that living in the past doesn’t keep her fueled. She begins to forge new connections, using what she learns from her emotional entanglements with those around her (in particular, her traveling companion, Ludo) to help her grow.

Spatial dislocation in Call Me Zebra is a pivot from Van der Vliet Oloomi’s debut, Fra Keeler, which is beautifully grounded in a single place. The movement from place to place can be disorienting — intentionally so. Zebra’s travels draw us into her tragedy of displacement and bereavement, a lens through which we might learn to empathize with exiles — both voluntary exiles like Ludo, and forced exiles, like Zebra’s father. Now, as the last in what she calls her lineage of “anarchists, atheists and autodidacts,” Zebra struggles to find a place where she is understood.

My life is far removed from Zebra’s. But in her, I recognize pieces of myself. Zebra senses the emotional energy stored in the spaces she traverses, and she hopes to use it to forge a new identity. Like her, I am entering a new phase of my life. I’m walking new paths in a new city, every day being shaped by these new places and leaving pieces of myself behind in them. I’ve taken root in the cozy bookstore, the lakeside bench, the neighborhood pub, the cluttered coffee shop. I recognize Zebra’s bittersweet nostalgia as she encounters spaces of importance. I feel it when I return to places from my own past, remembering the experiences I had there and recognizing how they have changed me since.

And in Zebra I recognize the women who have walked beside me: my mother, strong and stubborn; my friends, fierce, funny, frustrating; and my professors, like Azareen, who shaped my education and growth.

The representation of women in literature, music, film and television is under a great deal of scrutiny, and rightfully so. Enter Zebra. She is not the token Strong Female Character, invented to fill a diversity quota or inclusion rider. She is three-dimensional, nuanced and autonomous. She has the fiery independence of Stieg Larsson’s Lisbeth Salander and the endearing quirk of the title character in Frances Ha. Aggravating and endearing, weird and wonderful, characters like Zebra are necessary. I hope to meet more and more like her.

Grace Guibert is an associate editor at World Book Publishing in Chicago.