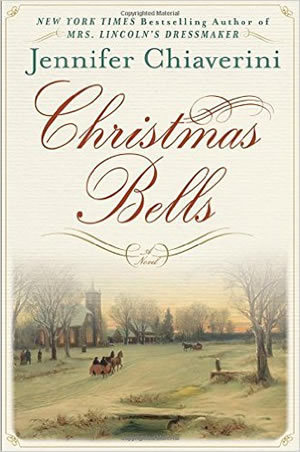

I had a tough time reading Christmas Bells by Jennifer Chiaverini ’91. It’s not that the historic fiction wasn’t well written. It wasn’t that I was bored. It’s that the sense of despair, of dread, of sadness that haunts the characters at Christmastime hits too close to home this year.

In the story, the tales of historic figures and modern characters are spun together in a piece that revolves around the poem “Christmas Bells” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The poem, the basis for the Christmas carol “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day,” is probably best known by its opening stanza: “I heard the bells on Christmas Day/ Their old, familiar carols play,/ And wild and sweet/ The words repeat/ Of peace and earth, good-will to men!” But the rest of the poem is far less merry. The book reveals that Longfellow was a mild abolitionist who took to his pen as the continent plunged deeper into a civil war which had no end in sight. At the time, he was also overcome by a series of personal tragedies, including the injury of his son on the battlefield. The poem, according to Chiaverini’s telling, was written in a state of misery.

I find myself drawn to the sixth stanza of Longfellow’s poem, “And in despair I bowed my head;/ ‘There is no peace on earth,’ I said; ‘For hate is strong,/ And mocks the song/ Of peace on earth, good will to men!’”

In the past few weeks, we’ve witnessed horrifying attacks in California, Paris, Beirut, Israel and Mali. America has now been at war for nearly 15 years, fighting a shapeless enemy we can’t seem to contain. I watch friends prepare to deploy while others come home shaped by what they’ve seen. And then I look to the pile of Christmas decorations in the corner of my living room. How do we celebrate the birth of our Lord when the evil He was born to save us from seems to have multiplied? How can we feel joyous and merry in the midst of violence and sadness?

In the story, Longfellow muses on similar questions, but he isn’t the only character grieving. The narrator changes for each chapter, and readers are introduced to a 21st century military wife waiting for news of her M.I.A. soldier-spouse. There’s the story of the schoolteacher whose music program is cut and who finds herself staring down unemployment. There’s the widow who has just lost her husband. A pianist, several children and a priest also take a turn telling their tales. The poetic thread that unites them is there, but it occasionally feels forced, as are some of the children’s narrations and mentions of Notre Dame.

Of the characters, Chiaverini’s Longfellow is the most developed and is a convincing version of the renowned literary figure. Drawing from diaries, biographies, letters and memoirs, she pieces together the life of the Longfellow family during the wartime years. The peek at the personal life of the notably private poet certainly makes for an intriguing read.

But what has stuck with me is the crux of the piece: Longfellow’s poem. The final stanza provides some hope for the characters and for readers today:

“Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:/ God is not dead, nor doth he sleep;/ The Wrong shall fail,/ The Right prevail,/ With peace on earth, good-will to men.”

Peace on earth, good-will to men.

Tara Hunt McMullen is a former associate editor of this magazine. She is now a freelance writer in North Carolina.