On the first page of Comedy in a Minor Key, Nico is already dead. Wim and Marie, a young Dutch couple who have been hiding the Jewish perfume salesman from the occupying Nazis, stand beside his body, consulting with their doctor about what to do.

Not so much consulting, really, as “standing indecisively near the bed, the way people stand when moved by fear and sadness at the same time.” Wim and Marie have grown close to Nico. This is a devastating personal loss, but also ridiculous in its particulars, one crisis replaced with another, each requiring the utmost secrecy. Nico has died not at the hands of the Nazis, but of natural causes. Now what?

Anxiety and sorrow infuse this 135-page novella, but author Hans Keilson also captures the awkwardness of it all — the human comedy. Nobody appears to possess great courage or grace under pressure, just a resigned sense of duty — to country, to religion — in the face of the inhumanity all around them, the minor key that subdues the mood during ordinary activities like dinner and coffee, laundry and dishes.

As they hover around Nico’s deathbed, warplanes whine overhead, the “dull, thudding pops” of the night’s first shots causing the house to shudder. By now familiar, the sound of the engines and the ammunition drifts in and out of their consciousness like the weather, attracting notice only as a diverting subject of small talk.

Wim and the doctor decide to carry Nico’s body to a nearby park later that night in the darkness of a new moon. It will be left there for the authorities to discover, hopefully untraceable to the house where Nico has been in hiding.

As Wim and Marie await the doctor’s return for their grim chore, the story wends back to the couple agreeing to an acquaintance’s request to offer refuge to a Jew, then to Nico’s introduction into their lives and a year of wary alliance. All three act in good faith, with generosity or gratitude as their personal situations warrant, but so much could go wrong. Each turning page feels like searchlight sweeping the darkness.

Will the cleaning lady find out? Do the neighbors suspect anything, and where do their sympathies lie? When Marie is away on an errand, should Nico risk retrieving the newspaper she usually brings to his room?

One day the scent of milk burning on the stove prompts him to emerge and turn it off, thinking Marie has left the house. She hasn’t, but at that exposed instant, of all possible times, the fishmonger appears with his catch, leading to a rushed moment of maladroit indecision about where Nico should hide.

Keilson combines quotidian routine and wartime suspense into an atmosphere that’s taut like a tightrope. Sometimes laughter feels like the only possible reaction, if not the appropriate one, to otherwise trivial situations fraught with existential dread.

None of these slices of life and death are laugh-out-loud funny. Keilson never condescends to make fun of these trapped people. Neither does he exploit the horror that haunts the house. Few authors could have been better prepared to negotiate that perilous emotional terrain.

A German-born Jew, Keilson himself went into hiding in the Netherlands as a 22-year-old during the war. He was already a published author and a psychoanalyst by then. Even while in his clandestine exile, Keilson treated Jewish children who had been separated from their parents. His medical practice in the decades that followed focused on children who suffered wartime trauma, a vocation he valued far above his writing.

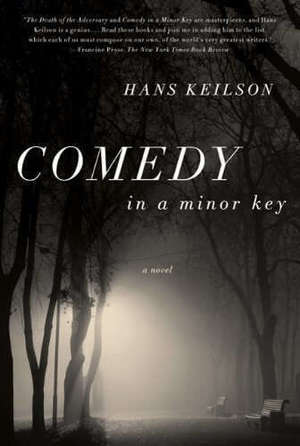

His 1962 novel, The Death of the Adversary, was a bestseller in the United States, but in the English-speaking world he spent most of his life in literary obscurity. Keilson published Comedy in a Minor Key in German in 1947. Only in 2010, a few years after a chance discovery by translator Damion Searls, did it appear in English, bringing a moment of celebrity for the novelist, then 100 years old. (He lived to 101.) Author Francine Prose hailed Keilson as a genius in The New York Times, to which the centenarian replied, “I’m not even a proper writer!”

I picked up the book during that publicity boomlet a decade ago and it’s been an occasional object of curiosity since, a little sliver wedged on the bookshelf between weightier works. After probably a couple dozen times perusing the blurbs and fluttering the pages, I finally sat down to read it, as fast and easy an experience as the reviews promised. As heavy, too, like Nico’s dead body. And light at the same time, like the scene of Wim and the doctor clumsily figuring out how to bear his stiff, unwieldy weight to the park.

Reading Comedy in a Minor Key during a pandemic deepens its historical resonance with contemporary echoes, faint though they may be in comparison to Nico’s brutal oppression and Wim and Marie’s perilous sacrifice. There’s the sense of suffocating confinement, of unknown risks in commonplace encounters, of enduring uncertainty about when it will end. Even dubiousness about whether a perceived ending can really be believed.

The vacancy Nico’s death leaves in the room upstairs, like a COVID vaccine, begins a new phase, but cannot bring the ordeal to an instant conclusion. Although Wim and the doctor get Nico’s body to the park without incident, the specter of detection still looms. At least they can see the figurative light through the blackout curtains.

Then Marie discovers an oversight that implicates the couple — or it might, they can’t be sure of anything. The possibility is enough to force them to find their own hiding place. Opening their home to Nico has not only failed to save him, but an unthinking act of care during his illness now threatens their own lives.

“You’re careful for a whole year, everything goes fine,” Wim says, “and then, right at the end . . . It’s almost enough to make you laugh!”

Almost.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.