In 1911, butchers at an Oroville, California, slaughterhouse found a man named Ishi starving in its corral. For thousands of years — thousands — Ishi’s tribe had lived in the forests of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Now he was its sole survivor, the last of the Yahi.

Soon Louis Kroeber, an anthropologist at the University of California, Berkley adopted Ishi, so to speak. The university’s Museum of Anthropology let him live within its walls and gave him a job. No longer a hunter-gatherer, Ishi became a janitor. When not sweeping floors, this stranger in a strange land demonstrated his fire- and tool-making skills to visitors. Three years later, the microorganism Mycobacterium tuberculosis found a home in Ishi’s lungs, and he died in 1916.

What befell Ishi fascinated George R. Stewart, an English professor who would become one of Kroeber’s faculty colleagues several years later. Stewart, who today is nearly as forgotten as the Yahi, wrote more than 25 books — novels, biographies and histories — some of which were bestsellers. Walt Disney was an admirer and told him, “The work you are doing is of much interest to us.”

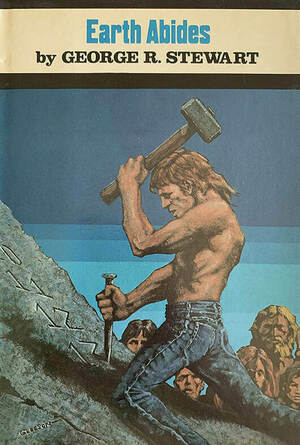

A recurring theme of Stewart’s writing is civilization — how and why things like justice, technologies, education and religion function, or don’t. His most acclaimed work — Earth Abides — won the 1951 International Fantasy Award, an honor it shares with The Lord of the Rings, which won six years later.

Suffice it to say, things fall apart big time in this post-apocalyptic novel when a new disease hits the fan. A virus. Everyone dies and does so quickly. In a passage that takes on modern resonance, Stewart leaves it to readers to decide whether the doomsday bug “emerged from an animal reservoir” or was “a vindictive release.”

Instead of dwelling on mayhem, Stewart serves up what is known in the trade as a “cozy catastrophe,” a term coined by science fiction writer Brian Aldiss, who explained that “the hero should have a pretty good time of it (a girl, free suites at the Savoy, automobiles for the taking) while everyone else is dying off.” Stewart’s hero, Isherwood Williams, a graduate student in geography, misses the upheaval thanks to his solo research trip in the Sierras and a rattlesnake bite he thinks may have immunized him.

He returns to a depopulated world. “Mankind seemed merely to have been removed rather neatly, with a minimum of disturbance,” we are told.

One doubts that is how victims viewed the matter. To read Earth Abides during our own current unpleasantness reminded me how relatively fortunate we are. Unlike our parents, we have no fears of polio crippling our children. Unlike our grandparents, we aren’t dealing with smallpox or typhoid or even the Spanish flu, which carried away otherwise healthy young adults by the millions. As deadly and disruptive as it has been, COVID is a relatively gentle reminder of what nature can do when it swings for the fences. After all, scholars say smallpox and other diseases killed as many as 90 percent of Native Americans American Indians, and aside from academics and Native Americans, few among us even know that extermination happened. Writes Stewart of his own mystery killer, “History was an artist, maintaining the idea but changing the details.”

Isherwood, who, naturally, is called Ish, meets his Eve, an older woman named Em. In what was likely a daring narrative move for 1949, when the book was published, Em is Black. She wants to have a baby. Ish does not, fearing Em might die in childbirth. Ultimately Ish concedes. “The match lived, not when it lay in the box, but merely when it burned — and it could not burn forever,” he reflects. “So too with men and women. Not by denying life was life lived.” Off he scurries to the university library for medical texts on childbirth.

Soon Ish presides over a tiny tribe of survivors who live idyllic lives in the Berkeley hills. It helps that the water system somehow remains active for years. Despite Ish’s kindly efforts, his tribe shows little interest in working together to improve their community or tend gardens. They dine on scavenged canned goods and beef from cows who graze conveniently nearby. Later Ish regrets having spent his leisure hours reading philosophy instead of medical texts and fix-it guides.

Much of the book’s hypnotic fascination comes from Stewart’s quiet, dispassionate professorial air. “When any creature reached such climactic numbers and attained such high concentration, a nemesis was likely to fall upon it,” he writes, speaking not of human overpopulation but that of the ants who invade Ish’s home. On some level, the whole darn end-of-the-world thing is like one big take-home exam for him. “Even though the curtain had been rung down on man, here was the opening of the greatest of all dramas for a student such as he,” Stewart writes.

Ish is, of course, Ishi’s mirror image, the last American. The tribe’s children become the first new American Indians. In an act that may have gladdened Ishi’s heart, Ish, having realized after 20 years that eating out of old cans is a dead end, teaches children to carve bows and arrows from lemon-tree wood and weave bow strings from thin rawhide strips.

Stewart seems to approve of the young ones’ back-to-nature ways. They pair shiny-riveted Levis with tawny mountain-lion-hide tops, complete with dangling claws. Short and brutish their lives may be, but they are blessedly free of civilization’s neuroses. “Yes, I am happy,” says Ish’s adult son. “Things are as they are, and I am part of them.” It is a distressingly blank-minded rejoinder in a book whose title comes from Ecclesiastes: “One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth forever.”

Readers may be relieved to learn that in Stewart’s pages abideth no cannibalism, ala Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Stewart had already covered that topic in his Ordeal Hunger, a history of the Donner Party, pioneers trapped in the Sierras during the winter of 1846-47 and who dined on the flesh of the dead.

Likewise, Satan headlining in Las Vegas could only happen in Stephen King’s The Stand. Maine’s maestro of the macabre has acknowledged Stewart’s influence on that lap-crushing epic. For his part, Stewart, ever the rational professor, sees the end of the world not in Manichean terms of supernatural good and evil but rather as something natural that will happen to ants and men alike. It’s all scything of the wheat.

George Spencer is a freelance writer who lives in Hillsborough, North Carolina.