Margaret McMullan, a writer of novels for both adults and young adults, and a professor at the University of Evansville in Indiana, learned to love books at the knee of her father, Jim McMullan. He was a businessman, not a writer, but they “became literary groupies together,” attending writing conferences and exchanging books, writes the daughter in her editor’s foreword. When her father died of brain cancer in 2012, she found herself not only bereft but wordless. “I couldn’t read or write,” she says, “perhaps because, in the end, my father was unable to read or write.” She was hungry for stories about her father — and, by extension, of all fathers. She wanted to think through her relationship with her father through the prism of other father-daughter relationships, so she could come to understand what she had been given and what she now had lost.

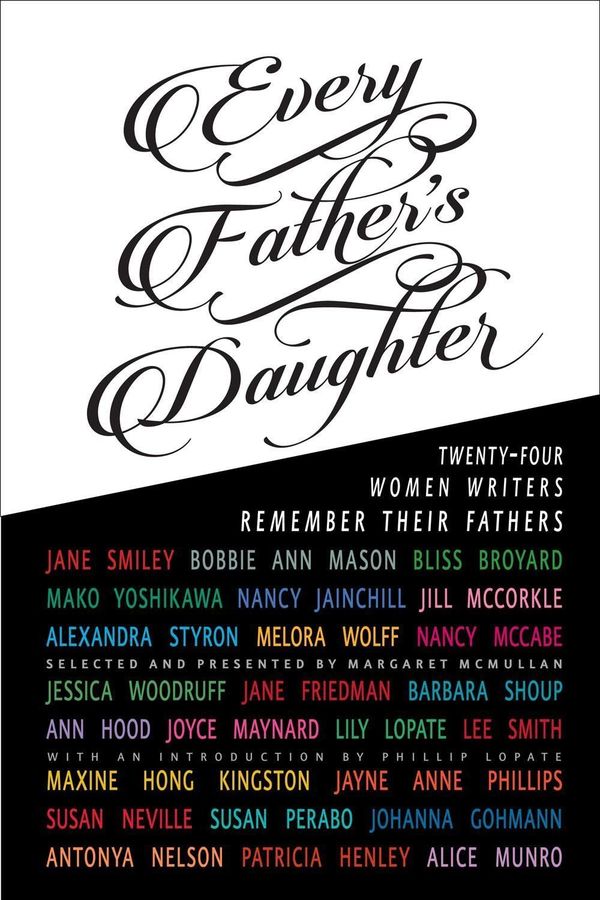

Thus Every Father’s Daughter was born. McMullan wrote to authors she admired, some of them friends of hers, some of them friends of her father’s, some of them authors the pair had never met but had read together. The contributors include the well-known (Jayne Anne Phillips, Jane Smiley, and Lee Smith) as well as some newer names (Jessica Woodruff, Jane Friedman). Each personal essay is prefaced with a photograph of the essayist and her father, which adds an intimate touch, a rounding of the portrait that follows.

In addition, McMullan provides a short description of why she chose to include the essay, mentioning, for example, that she and her father had heard Bliss Broyard speak about her biracial heritage at her father’s alma mater. As a result, we read Broyard’s essay both for what it teaches us about Broyard, and for what we imagine McMullan and her father liked about Broyard. The anthology contains not only essays to read; it is also a ghost-memoir of the act of reading.

Some of the essays are celebrations of unquestionably excellent fathers. Susan Perabo begins “What He Worked For” with a paean to summers’ family road trips, “first in our old red Ford and later in the wood-paneled station wagon you see when you close your eyes and picture 1977.” Perabo’s family would stop at Howard Johnson’s, where, every time, she would order the hot fudge sundae, despite the fact that three bites in, every time, she’s have to lay down her spoon and confess defeat. Her more practical mother suggested she should order a more modest dessert, but her father would counter, knowing this was a “memorable mini-extravagance,” that “This is what I work for.”

Perabo describes how, as a child, she had little understanding of what work her middle-class father did to pay for the sundaes and Howard Johnsons, content to know merely that her father was in “community relations” at Ralston Purina. Only at her father’s retirement party did she learn the extent of his work outside the home, finding that he had touched the lives of “thousands of people I would never know. Generosity, which came so naturally to him, was his job.”

Some of the essays deal with difficult, dangerous, or absent fathers. Mako Yoshikawa’s father was an internationally renowned physicist, a workaholic to such an extreme that he was little more than a moody stranger, drinking to cope with his stress, falling into a depression every October when he didn’t win the Nobel Prize yet again. Yoshikawa’s memoir is a psychological excavation that opens with his tiny funeral — fewer than 50 mourners attended — and moves backward with a desire to understand. The reader can’t help but gaze at the photo that prefaces Yoshikawa’s essay showing her father, age 4, in an elaborate kimono, gazing seriously at the camera, and feel that the daughter’s efforts to understand her father must have caused some pain but much healing, too.

A strange thing happens as we read these women remembering their fathers, for we inevitably think of and evaluate and sometimes eulogize our fathers, too. We consider their childhoods and how they affected our childhoods, think of their legacies and how they affect our own. The subtitle of the book mentions the 24 writers remembering their fathers — but every copy christens a 25th writer, for whether the words are written down or not, we read these memoirs and we begin our own.

Beth Ann Fennelly is an associate professor of English and director of the MFA Program at the University of Mississippi.