For readers who may not recognize his name, Sam Hazo ’49 is the most complete — and certainly the most productive — man of letters who ever graduated from the University of Notre Dame. He is known best as a poet (he has been a National Book Award finalist) and as the founding director of the International Poetry Forum in Pittsburgh. He is also a novelist and playwright, translator and author of numerous essays on literary and intellectual subjects, as well as professor emeritus of the Duquesne University. Former students and audiences know him as a riveting reciter of his poetry.

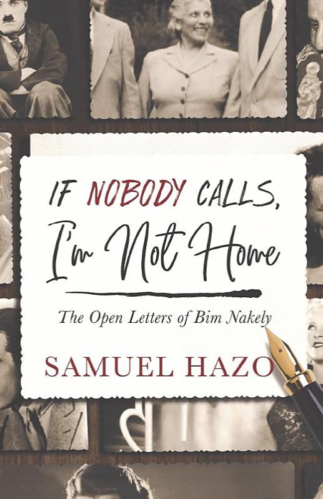

Not even Sam can tell you exactly how many books he has written (one his several publishers guesses about 60) but I write to say that his latest novel is an absolute gem. Like Ring Ladner’s baseball classic, You Know Me, Al, Hazo’s If Nobody Calls, I’m Not Home, takes the form of a series of letters written in 1964-65 by Bim Nakely, a 73-year-old retired factory seamstress who never married; instead, she raised her deceased niece’s two boys “as if,” she keeps reminding us, “they were my own.”

In fact, Bim devoted her life to them and now that she’s seen them grow up, graduate from college, marry and establish families of their own, she gets to feeling like “an extra on television.” At night in bed she “hears the house talking to itself.” The sense that her life’s served its purpose gets her down at times. “It’s hard to admit that I’m not needed, but that’s the God’s truth,” she confides in her first letter. But at moments like these, she writes, “I just tell myself that God might be keeping me here for have a purpose I don’t even know.”

This letter is addressed to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who is already 19 years dead — but so are Mae West, Ernest Hemingway, Charles Lindbergh, Rita Hayworth, Babe Ruth and all the others she writes to. Of course, none of the letters are sent, nor were they meant to be. But they sure do communicate who this wonderfully invented character is, what her life has been, what the world she knows is like, all setting the reader up for the unexpected life purpose that eventually emerges.

In Hazo’s hands, the epistolary novel turns out to be a supple literary form. When we write a letter to someone, we not only have that person literally in our mind, we are also probing what that person means to us. Bim (her given name is Barbara) is what my late older sister would have praised as “a real piece of work”: having held her own as a single woman inhabiting a male-dominated blue-collar world, she’s not at all shy about giving these notables she admires sane advice and putting the kinds of questions to them that a fawning fan would blush to ask.

For instance, she clearly disapproves of violence inherent in war, boxing and bullfighting, and wants to know from Hemingway what he gets out of all three. She likes A Farewell to Arms, but clearly disapproves of his taking his own life. He should have considered what effect his suicide would have on his boys, she admonishes Papa.

Bim, too, we learn, has been visited by the same dark temptation and has, after thinking of how her suicide would affect her own two boys — not to mention the tongue lashing she’d get from “St. Mary” (the Blessed Virgin) on the other side — decided to put it out of her mind. Still, Death itself is seldom far from her thoughts, and for good reason. Her doctor has told her recently that she has a weak “ticker” and that this will eventually do her in. One of her motifs is how to answer Death’s inevitable knock at the door, or more precisely the knock of what she has decided to call “Mr. Nobody” — hence the book’s title.

I particularly enjoyed Bim’s letters to female movie stars of her era. She, like they, are pre-women’s movement and thus her remarks are free of ideological clichés. Bim lauds Mae West’s take-me-as-I-am, girth-and-all attitude. “Heavy or not,” she writes, “you always acted (around men) as if you owned your body and not visa-versa. In contrast, she chides Rita Hayworth for letting men use her. “I never had a man, if you know what I mean,” she tells the glamorous pin-up of the ‘40s. “But you had a few . . . I understand what it means to have none, and I know enough married women to know what it’s like to have one. But I’m curious to know what it’s like for a woman to . . . go from one man to another.”

From letter to letter it’s Bim’s unique voice that is in control, and from which emerges a character in the round and a plot that slowly unfolds. This is not one of those books that lead some reviewers to claim they “couldn’t put down.” I liked putting this short novel down from time to time, the better to savor that voice and what the latest letter added to the whole.

All of us should have at least one Bim Nakely in our lives. And thanks to Sam Hazo, we can.

Ken Woodward, a former religion editor of Newsweek and author of four books, currently serves as Writer-in-Residence at the Lumen Christi Institute at the University of Chicago.