I bought Mary Karr’s Lit in Washington Hall, minutes after her keynote address to the group of Catholic writers who gathered at Notre Dame in the summer of 2017.

Naturally the anonymous, workaday rabble of us had showed up expecting Karr and her trademark Texas wit in person, wondering what she’d be projecting on the massive movie screen centered behind the podium. Instead, it was Karr herself who appeared from the shoulders up, Skyping in from her Syracuse, New York, apartment where she’d fallen and injured herself days before, leaving her too banged up for the flight to South Bend.

Whatever the influence of her painkillers that night, the hour that followed was intimate, the room too dark for me to take notes as Karr made us snicker and howl and performed remote open-heart emotional surgery around the room. If the unusual circumstances were a sneaky sales schtick to prompt us to buy more of Karr’s sass, her raw and hilarious storytelling and her hard-won spiritual and creative wisdom, it worked. I had to muscle up to the book table like a thirsty newbie at a New York nightclub.

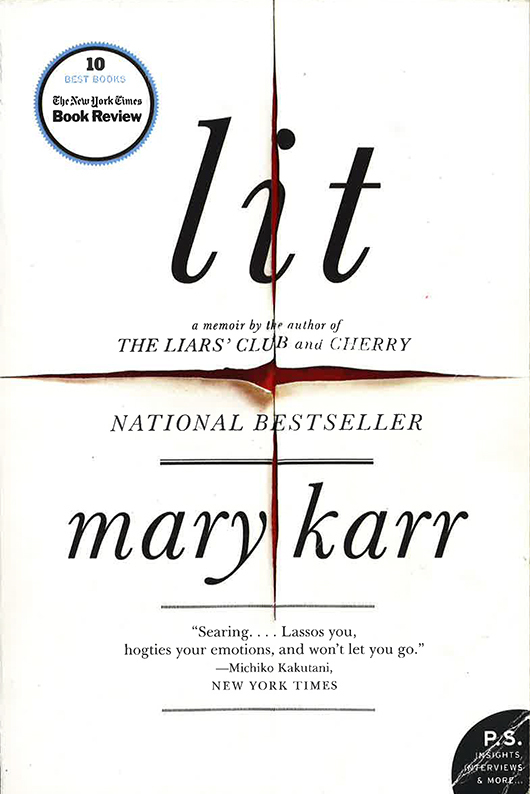

The spread offered several options, including Sinners Welcome and a few other volumes of her poetry, as well as each of Karr’s three national-bestseller memoirs — The Liars’ Club, her literary breakthrough in 1995, a harrowing tale of growing up in an abusive, coastal Texas home raised by agnostic alcoholics, and Cherry, her account of escape from her small and dangerous hometown into a sort of Dorothy Parker, fresh-hell independence, and her first encounters with sexuality and addiction.

Then there was Lit, presented to me as the story of Karr’s religious conversion in the late 1980s and early 90s. The book is far more than that, but it is that: a tale of a slow, excruciating dark night of wrestling angels and demons — her past, her present, her upbringing and her own parenting, her drinking and her unraveling marriage, a suicide attempt and institutionalization, her protracted poverty and creative paralysis. The bout only sharpened her sensitivity to detail, irony and humor, leading to her Catholic baptism and publication of The Liars’ Club.

I haven’t read many memoirs, so I confess I can’t quite understand the writerly snootiness that downplays them as a literary genre, but at its vivid and flowing and honest best, memoir makes for unbeatable reading. Karr is among those writers of the past 25 years credited with “reviving” the form. Thus the writer Samantha Dunn dubbed her “grande dame memoirista” in a Los Angeles Times review. Susan Cheever praised Lit, published in 2009, as “the best book about being a woman in America” she’d read in years.

I’m unqualified to comment on that. But it seems to me, now that Catholics are entering the McCarrick era of renewed deception, betrayal and distrust, of attempted cover-up and ultimate, bitter disgrace, Karr’s work — and the inspiration she offers other writers — may be as important to religion as it is to conversations about literature and gender. Right now, the Church needs its writers more than ever.

At that Notre Dame writers’ conference last summer, convened with no lower ambition than to re-form the all-but-dead American Catholic literary scene that once produced spiritual classics like Thomas Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain and National Book Award winners like Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy and J.F. Powers, the Church’s need seemed mostly a matter of re-kindling the Catholic imagination, of privileging beauty as a worthy peer of truth and goodness, of restoring art’s place in Catholic culture.

No longer. The time, with painful urgency, has come for truth-tellers who can probe the contusions and lacerations of their bodies and souls, the brokenness that befalls us all, and relate what they find to our collective quest for anything like the peaceable kingdom.

We need poets, novelists, short-story magicians, essayists — and maybe searingly honest memoirists like Karr above all — if we care about Christian authenticity and credibility, or hope to have anything to say about sin and redemption, about our alienated humanity and our desperate, lonely need for a better world than this one. These writers aren’t saints, and they know it. The best among them refuse to posture as moral exemplars, much less as soothing spokespeople in times of fear, uncertainty and moral collapse.

Which means they’re better positioned to speak to us of true mercy. Karr lives and writes, we learn in Lit’s closing lines, “not to prove myself worthy but to refine the worth I’m formed from, acknowledge it, own it, spend it on others.”

Addressed more to the nonbelievers of Karr’s youth and young adulthood than it is to her fellow Christians today, Lit is one of those books every Catholic — current, former, future — should read, though I can think of a great many Catholics who wouldn’t like it. This isn’t family-friendly Christian music. This is Johnny Cash’s haunting hellraiser-turned-preacher fronting U2 on “The Wanderer.”

God doesn’t even enter the picture until the book’s halfway mark when Karr, reluctantly attending her first alcohol rehab meetings after years of hopeless alcoholism and self-loathing, is encouraged to reach out to her higher power.

“Higher power my rosy red ass, I can hear my daddy saying, and Church is a trick on poor people,” she writes. Three dry months later, Karr breaks down after a poetry reading at Harvard and, at a dinner that night to celebrate her work, hears her “puppet mouth ask for a martini.” She wrecks the car on her way home.

Later, after a come-to-Jesus talk with a 30-year-old hospital intern and sobriety speaker whose childhood was more horrifying than Karr’s, she acknowledges that she’s “trying to start hearing the word God without some reflexive flinch that coughs out the word idiot.”

That night, she utters the first prayer of her life. “Higher power, I say snidely, Where the f--- have you been?”

“Catholic literature is rarely pious,” the poet Dana Gioia pointed out in a 2013 essay for First Things that elicited multiple responses in Catholic journals and prompted the Notre Dame writers’ conference. Pointing to John Kennedy Toole, Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, Muriel Spark and dozens of others whose varying degrees of religious faith and moral failing are readily known, Gioia continued: “In ways that sometimes trouble or puzzle both Protestant and secular readers, Catholic writing tends to be comic, rowdy, rude and even violent. Catholics generally prefer to write about sinners rather than saints. (It is not only that sinners generally make more interesting protagonists. Their failings also more vividly demonstrate humanity’s fallen state.)”

For some reason, the American South is especially fertile ground for such writers, and for such writing. Karr, like her godfather and fellow Southern memoirist Tobias Wolff, are part of the same tradition as O’Connor and Percy and a good many others whose names seem a little dustier today. As an unabashedly cafeteria Catholic who still wrestles with Church teaching on several issues as she continues to seek and to pray, Karr isn’t a writer like O’Connor in outlook or writing style so much as she’s someone O’Connor might have written about.

O’Connor, I think, would say we’re all someone she’d write about. The grotesque is ubiquitous. So, too, is grace. What we need more of is humility, the good-memoirist’s cardinal virtue of knowing oneself at her true worth, and of presenting herself as no more and no less.

In Lit, the post-conversion Mary Karr contracts the services of a Franciscan nun for a months-long workout in the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius. She wastes no time in frankly relating her unmarried desire for sexually active relationship. Her new spiritual director kindly suggests that Jesus might ask whether she should be “vulnerable to a man without some spiritual commitment.” The two eat their cookies, then pray for each other’s “disordered attachments.”

“Mine,” Sister Margaret says, “involves pride and cookies.”

“Mine,” Karr replies, “involves pride and good-looking men.”

Together they bow their heads.

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.