Steven Spielberg watches the The Best Years of Our Lives every year. Francis Ford Coppola says it’s one of the 10 best movies ever made. Martin Scorsese loves it, too. The film swept the Oscars in 1946, winning honors for best picture, director, actor and supporting actor, screenplay, editing and music. It also achieved the seemingly impossible feat of snagging two Academy Awards for U.S. Army veteran Harold Russell, the only time an actor has won two Oscars for a single performance.

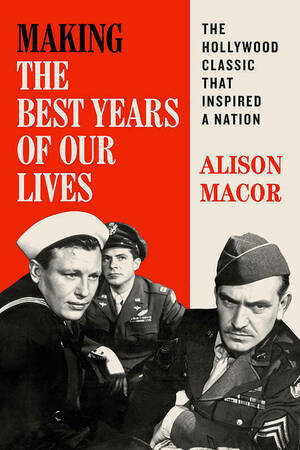

Best Years follows three American servicemen as they struggle to adjust to peacetime life after World War II in the fictional Boone City, a stand-in for Cincinnati. The highest-grossing film at that point since Gone with the Wind, this nearly three-hour epic explores the resilience of the human spirit. Film historian Alison Macor ’88 puts it in context in Making The Best Years of Our Lives: The Hollywood Classic That Inspired a Nation (University of Texas Press, 2022).

“The film and its cast humanized even the most troubled and disturbing veterans and showed audiences how to have compassion for those struggling to leave the war behind,” writes Macor, a former critic for The Austin Chronicle and the Austin American-Statesman.

Macor’s book traces the film’s production history — from its origin, when the wife of film mogul Sam Goldwyn spotted a 1944 Time magazine article about the home-front trials of returning servicemen to the revolutionary multiplane, deep-focus techniques of cinematographer Gregg Toland, and the criticism the film received for supposedly being anticapitalist and subversive.

Not convinced that Best Years is worth a look? The movie offers unsettling parallels with today’s America. Characters bemoan the “food shortage all over the world.” They fear the possibility of “widespread depression.” Banner headlines warn of a new war, and worries fester about America and Russia using guided missiles to hurl atomic bombs at each other.

Here’s proof of the film’s greatness: It crushed It’s a Wonderful Life in every awards category. “It says something about the American public of 1946 that they preferred the realistic, astringent honesty and quiet resolution of Best Years to the fantasy feel-good solution that papered over the panic-stricken despair of It’s a Wonderful Life,” critic Jonathan Rosenbaum once observed. (Perhaps if moviegoers had known that B-24 pilot Jimmy Stewart suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, they would have viewed his bedraggled on-screen freakout in snowy Bedford Falls in a different and more serious light.)

With millions of men being demobilized, what was called “the veterans problem” was on everyone’s mind, and Best Years lassoed the nation’s zeitgeist. One fan called the movie “a training film for all of us.” Historian David Gerber wrote in 1994 that many Americans at the time believed “every veteran was a potential ‘mental case,’ even if he showed no symptoms.”

The film opens with chance meetings on the transport plane home. Army sergeant Al Stephenson (Frederic March), a banker in civilian life, has seen bloody action in Okinawa. He yearns to return to his wife Milly (Myrna Loy). Disillusioned, he slides into alcoholism.

B-17 bombardier and Distinguished Flying Cross recipient Fred Deery (Dana Andrews) can only find work as a soda jerk. Worse, his wife, Marie (Virginia Mayo), leaves him. “I gave up the best years of my life, and what have you done? You flopped!” she smirks. When Fred falls for Al’s daughter Peggy (Teresa Wright), Al orders him to dump her.

Sailor Homer Parrish (Russell) lost both hands when his aircraft carrier sank. Instead of fingers, Parrish has metal hooks. The apple-cheeked Russell, like his character, suffered the same fate during the war when TNT exploded in his hands. Homer, whose name reflects his odyssey, refuses to believe that his prewar sweetheart, Wilma (Cathy O’Donnell), still loves him.

Postwar audiences were staggered by this first-time Hollywood actor’s performance. During WWII, no images of maimed soldiers had appeared in the press. At the time, people with disabilities were regarded as freaks best kept hidden in back bedrooms. Parrish deftly uses his hooks to light cigarettes, play the piano, hold silverware and even — in the end — slip a ring on Wilma’s finger. All he wants is to be treated like everybody else. “I got sick and tired of that old pair of hands I had. . . . So, I traded ’em in for a pair of this latest model,” he jokes.

The academy, not thinking Russell could win an Oscar for his acting, gave him a special award for “bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans.” When he took the acting award later that evening, “the audience erupted as if at a sporting event,” Macor writes.

For decades afterward, Russell served on the President’s Committee on the Employment of People with Disabilities, retiring in 1989 — shortly before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. “If you look carefully, you will see Harold’s DNA stamped all over that legislation,” Macor quotes one activist saying.

Director William Wyler, who helmed Ben-Hur, Roman Holiday and Mrs. Miniver, was the perfect man to direct the movie. To film the documentary The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress, he flew B-17 combat missions. “This is life at its fullest,” he said of those terrifying sorties.

Wyler knew something about loss. Thanks to the bomber’s thunderous engines, he returned home deaf — a broken man. “He talked as if his life was over, not only his career,” said his wife. Later, hearing returned in one ear. “Who better to make a case for the picture’s potential healing power than Wyler, himself a wounded vet?” asks Macor, who notes that Wyler, whose mother was Jewish, had emigrated to the United States from Europe as a teen.

Lest anyone think Best Years is a tough-guy movie, Loy received top billing, and the film showcases its three female leads. Their steadfast love helps redeem the men — and their relationships. At various points, we see each leading lady tuck her man under the covers.

First-time viewers may feel the film’s most gripping scene comes when Homer invites Wilma to his bedroom. The interlude, says Macor, combines “fear, anxiety, hope, and dread.” But Homer has no desire to seduce Wilma. Instead he wants to show her how helpless he is without his prostheses. “There were delicate problems in bringing a boy and a girl to a bedroom at night . . . without presenting Homer’s hooks in a shocking or horrifying manner,” Wyler recalled. “As a matter of fact, we felt we could do quite the opposite and make it a moving and tender love scene.”

For me, a more astonishing moment comes when Peggy confronts her banker father and proper mother with the news that she is in love with the married Fred. She knows the floozy Marie has contempt for her milkshake-mixing husband, that Fred is capable of more. To her dumbfounded parents, the teary-eyed Peggy barks, “I’m going to break that marriage up!”

Adultery was not something the Motion Picture Production Code normally promoted, nor would another scene involving Peggy have pleased it. When Al asks his wife if their daughter can handle herself around boys, she tells him in a winking sort of way that Peggy’s work in a hospital taught her plenty about contraception — without using the word.

Best Years has personal significance for me. My father had his own military troubles. He had to leave Annapolis in 1934 when, during his third year at the Naval Academy, his annual eye exam revealed he needed glasses. Back then, officers had to have 20/20 vision.

Being a diligent young man, he earned engineering degrees at Virginia Tech, served in the Navy reserves, reported for active duty in the fall of 1941, and married my mother three days before Pearl Harbor. He served as a shipyard officer during the war in New Orleans and in Galveston, Texas.

The family mystery begins when he demobilized. For many months, he and my mother lived apart — she on her parents’ Georgia farm, he on his parents’ Virginia farm. Perhaps he hoped to work in his family’s general store or return to his prewar job at the Tennessee Valley Authority.

But my father was no country boy. He said his father once told him, “Frank, if you don’t get in here and learn how to milk this cow or shoe this horse, you’ll never amount to anything.” Instead, he’d gotten his teenage kicks taking apart the family’s radio and car, experimental exploits that no doubt left my grandfather anxious.

Thanks to a letter written by a senior officer, the Navy took my father back in 1949. He then served nearly 25 years and rose to the rank of captain. Neither he nor my mother ever talked about that long period of separation, at least not with their four sons. My father may have felt the struggle for work was embarrassing. Maybe he was a soda jerk for a while.

Trauma, like courage, comes in many flavors, some more bitter than others. Macor quotes Russell: “For me, that was and is the all-important fact — that the human soul, beaten down, overwhelmed, faced by complete failure and ruin, can still rise up against unbearable odds and triumph.”

George Spencer is a freelance writer who lives in Hillsborough, North Carolina.