My childhood would have been poorer had my parents and I not watched The Mary Tyler Moore Show together every Saturday night. It was wholesome (at least to my 10-year-old mind), heartwarming and funny, and, boy, was Mary pretty. It is fascinating now to look back and consider how much I didn’t know about the show’s influence as an artifact of cultural history — or the real-life struggles of its star.

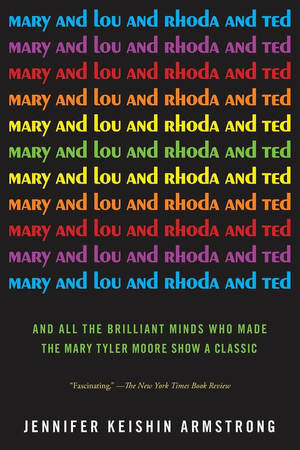

The 2013 book Mary and Lou and Rhoda and Ted presents itself as a comprehensive exploration of the show’s creation, actors, episodes and impact. Author Jennifer Keishin Armstrong, a pop-culture writer who’s penned similar books about Seinfeld and Sex and the City, hits the mark best when she delves into the real-life soap opera behind the show’s creation.

The consciousness-raising sitcom almost didn’t get on the air, but from 1970 to ’77, Mary Tyler Moore often ranked among TV’s top 10. It won 29 Emmys and spun off three other programs. With each season, viewers could see Mary’s confidence grow. She turned a generation of young women on to the notion they could have happy homes and careers.

The premise was revolutionary for the time: to explore the workplace and dating life of Moore’s sexy yet adorably goofy heroine, Mary Richards. What would it be like to be the only woman in an all-male newsroom at a third-rate Minneapolis television station?

Armstrong interviewed creators, James L. Brooks and Allan Burns, and production company executive Grant Tinker, then Moore’s husband, about the show, starting with their battle to get CBS to pick it up. In those dark ages a half-century ago, network gatekeepers thought a sitcom about a single woman with a job would be as welcome as a chicken bone in viewers’ throats. There was another problem, and it was a doozy for the time: Mary Richards would be a divorcée.

The pitch meeting took place on a top floor of Black Rock, the network’s Manhattan headquarters. “It was like something straight out of Kafka,” Burns recalled.

“The audience will think she divorced Dick Van Dyke,” one executive moaned. Moore and her flip hairdo had become stars in 1961, when she created the role of Rob Petrie’s cheery wife, Laura, in Van Dyke’s self-named sitcom.

That show also had challenged mores. Unlike the prim-and-proper TV couples of the Eisenhower era, this New Frontier pair had the hots for each other. Moore’s frolics in calf-bearing, form-fitting capris caused national heart palpitations reminiscent of Elvis’ hip-shaking antics.

But her career went nowhere after The Dick Van Dyke Show went off the air in 1966. The classically trained dancer would appear in a string of dud movies and starred as Manhattan geisha Holly Golightly in a Broadway version of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. It died in previews.

The new TV show might have been her last gasp. As a CBS executive told the crestfallen creators, “Our research says American audiences won’t tolerate divorce in a lead of a series any more than they will tolerate Jews, people with mustaches, and people who live in New York.”

“Brooks and Burns could form no logical response to this, except perhaps to note that Mary would be none of the other three,” Armstrong reports.

There was yet another problem: Mary Richards was 30, teetering on spinsterhood. At least that’s how adults viewed such a woman in 1970. Burns and Allan struck a deal with CBS that shaped the backstory and softened Moore’s departure from the super-housewife norm established by previous sitcoms. Viewers would learn in first episode that after putting her beau through med school, he jilts her. Still, it is hinted they lived together. In one episode she quips, “I’m hardly innocent. I’ve been around. Well, maybe not around, but I’ve been nearby.”

In the show’s intro, wide-eyed and biting her lip, she drives into big, bad Minneapolis in her virginal white 1969 Mustang. No dud compact car for frisky Mary, who has no shortage of suitors.

Sonny Curtis, one of Buddy Holly’s Crickets, wrote the show’s theme song, “Love is All Around” after merely being told the gist of the show. The “Texas farm boy” won the right to sing his own song on air only after Andy Williams turned the job down, but his songwriting sensibility was smack-dab perfect, Armstrong writes. So apt were his tune and lyrics (“How will you make it on your own?”) that Allan and Burns worried nothing they wrote would capture Mary’s essence so deftly.

Anyone who saw Mary Tyler Moore will remember how that intro ended: the star twirling in a crowded downtown intersection, flinging her black and turquoise beret heavenward. The moment was a highly coded act of cultural rebellion, given the hat’s “associations with rebels (see beatniks, Black Panthers) as well as girlish dreams of European sophistication,” Armstrong writes. It was a subversive symbol of her “graduation into her new, single, adult life in the city.”

Even with the network execs placated, the pilot episode bombed before its live audience. Some people walked out in mid-scene. “Nary a chuckle escaped from the bleachers,” writes Armstrong.

That night a bereft Moore fell into bed weeping. When Tinker, who had witnessed the debacle, saw this pathetic sight, he called the show’s producers. His phone message consisted of two threatening words: “Fix it.”

Moore wasn’t the problem. Multiple woes had beset the taping. A broken air-conditioning system left the audience sweltering. The audience hated Mary’s dumpy, wise-cracking neighbor Rhoda, played by Valerie Harper. (She was both Jewish and from the Bronx — though mustache-less.)

That issue was solved with a rewrite, but another problem remained — Ed Asner had yet to master his character, the gruff news director, Mr. Grant, who keeps booze in his desk. In the first episode, Mary applies for the job of secretary. During the interview, Mr. Grant grills her about her religion and marital status, topics that were already taboo under federal law.

Grant says she can have the associate producer’s job (and earn less). Mary jumps at the chance.

“You know what?” he asks her. “You’ve got spunk.” When she nods in agreement, he hits the punch line: “I hate spunk.” But in that first taping, Asner, accustomed to playing tough guys, came across as “humorless and bullying,” according to Armstrong.

Burns and Allan scheduled a second live taping. The director coached Asner to deliver the line with “controlled anger,” not “all-out rage,” says Armstrong. This time, the studio audience roared.

Two years later, Mary Richards and Mary Tyler Moore had long since made it. The producers canned the theme song’s maudlin line, “How will you make it on your own?” and Curtis replaced it with two confident queries: “Who can turn the world on with her smile? Who can take a nothing day and suddenly make it all seem worthwhile?”

When Moore and her gang signed off in 1977, the last episode became a national event. Its final scene has the ensemble engage in a sniffly group hug after all of them, except Ted Knight’s odious news anchor, Ted Baxter, are fired.

As a fan, I wished the author had asked what future lay ahead for Moore’s character, a question the show leaves unanswered. In the final season, one episode sends her on a disastrous date with Mr. Grant. Another has the men in the office fantasizing about what it would be like to be married to her. Ted Baxter asks, “How do you figure a terrific woman like Mary never got married?”

The implication is clear — Mary Richards is an old maid, and a life without a man’s love seems a sad and lonely fate for an appealing character who had won the hearts of millions.

What of the women who idolized Mary? CBS and its advertisers manipulated the heck out of this new demographic group. It called them “‘Life Stylers’: women who embraced liberation in their everyday lives without necessarily identifying as feminists,” Armstrong notes. “These women were Mary Richards. And they needed fabulous clothes, beauty products, and furniture to feel like the independent women they wanted to be.”

The book’s acknowledgements thank the writers for agreeing to the interviews. But Valerie Harper was the only cast member to talk to Armstrong. The person most notably absent is the star herself.

Like her fans, the real Mary may have envied her TV twin’s life but in Armstrong’s book we learn relatively little about what Moore thought of the show. Moore had suffered childhood sexual abuse and smoked three packs of cigarettes a day. Her brand? Silva Thins, according to Armstrong. The headline of one of its contemporaneous ads read, “Cigarettes are like women. The best ones are thin and rich.”

She was an alcoholic — as was Tinker. Their union was a second marriage for both of them, and it ended in divorce in 1981. Moore smoked and drank long after being diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in 1969. She admitted in her autobiography that she was not much of a mother. Her only child died as the result of a self-inflicted gunshot wound that was deemed accidental.

Armstrong makes only one reference to Moore’s alcoholism, calling it a “social drinking” problem, but it would land the star in the Betty Ford Clinic. The passing mention of this key subject made me wonder why the author had so little to say about other aspects of the show, such as conflicts between cast members or writers’ bitterness over revised scripts.

Armstrong comes closest to exploring Moore’s psyche when she writes, “Her most revelatory answers [to reporters] were about her own guardedness. ‘I’m cautious in my dealings,’ [Moore] said. ‘I’m a hang-back person when things get uncomfortable. I’m reserved, I guess.’”

Translation: You’re seeing a carefully constructed façade. Buzz off.

Maybe we’re better off knowing nothing of an artist’s private life. Moore’s art soared as high as her beret. Creating the show with her name on it gave her respite from her private woes. She took her nothing days and suddenly made ours seem more worthwhile.

George Spencer is a freelance writer based in Hillsborough, North Carolina.