Twenty-five cents. Maybe it was 50. That was my allowance. Every Saturday morning, I trekked with my father on errands. At last, we’d get to the drug store. Coins in my sweaty little palm, I’d dart to the spinning comic book rack.

Maybe I’d grab the new issue of Marvel’s Tales to Astonish. It paired Iron Man and Sub-Mariner stories, both for 12 cents. If I was lucky, I’d find Tales of Suspense. It starred the weirdest combo ever — Dr. Strange and Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.

I was nuts for DC Comics, too, but there was something about Marvel. This was 1968. Marvel was cool. Its Silver Surfer flew a surfboard through the cosmos. How could not-a-hair-out-of-place Superman compete?

Marvel had a family feel missing from DC. Like big, strong older brothers, its heroes hung out together. They protected puny me and the universe. Of course, I eventually left childish comics behind as teens do. So how weird is it that superhero worship is now the norm for millions of adult moviegoers?

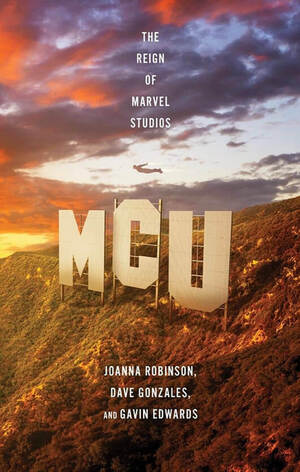

Not so weird after all, thanks to an array of super-executives who used Earth’s greatest do-gooders to sell toys, rather than truth, justice and the American way. You, too, can learn their secret business origin story in MCU: The Reign of Marvel Studios by pop culture authors Joanna Robinson, Dave Gonzales and Gavin Edwards. Their book recounts the behind-the-scenes, gossip-galore rise and possible fall of the most lucrative movie franchise there ever was.

For comic book fans seeking insider lore, you’ll learn, among other things, that Edward Norton’s self-indulgent behavior on set cost him the chance to play the Hulk again. And an entire chapter dwells on how the Hulk’s shade of green is created (as a nod to the MCU’s teaser scenes that follow each movie’s credits, it’s hidden in the index).

But the authors have more to offer here than gossip and trivia. What makes MCU worth reading even for nonfans is its exploration of the business realities behind blockbuster moviemaking.

It’s all about the toys. As one unnamed source told the authors, “Whether it’s comic books or movies, these are all loss leaders for the merch, which is where the real money is.” In the words of another, the movies “moved plastic.”

Since the first Marvel Studios film — 2008’s Iron Man, the company has made 33 epics that have grossed more than $30 billion worldwide. Thirty-three movies with semi-unified storylines and similar visual styles sets a film-franchise record. That’s more movies than there are in the James Bond or Star Wars catalogs.

“The Marvel method could have ended up as an assembly line,” the authors claim. “But as with the old studio system, it has resulted in a mix of entertaining diversions and inarguable masterpieces.”

Whether or not the MCU films are “inarguable masterpieces,” Marvel did something Hollywood hadn’t seen since the 1950s: It recreated the studio system by locking actors into long contracts and hiring staff writers and visual artists. Just as studios once owned theater chains, Disney — Marvel’s owner since 2009 — created a streaming distribution system in 150 million homes.

Besides ruling cineplexes everywhere, Marvel further dominated home screens with at least 25 often forgettable TV shows such as Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, Iron Fist, The Defenders and even She-Hulk: Attorney-at-Law.

If you’ve never heard of those programs or the movies The Eternals (2021) or Morbius (2022), the moral of this story — and the book — is as old as Aesop’s “The Goose That Laid the Golden Eggs.” In the fable, the bird’s greedy owners killed their feathered meal-ticket, thinking it had 24-karat innards. So it is with Marvel.

Consider the studio’s tortured corporate history. What started as Timely Comics in 1939 was sold in 1968 to Perfect Film and Chemical Corporation, which was acquired by New World Pictures in 1986 and sold in 1989 to hostile-takeover kingpin Ron Perelman.

After Marvel declared bankruptcy in 1996, Perelman would dish his distressed asset to toy company owner Ike Perlmutter and his toy-designing partner Avi Arad, who already held an “exclusive, perpetual, royalty-free license” to all of Marvel’s characters. On his way out, “Perelman wanted rumors of a movie (raising the value of his intellectual property and spurring sales of ancillary products), but not an actual movie that could flop and hurt the brand.”

After Perelman’s exit, Perlmutter and Arad made sure that even if a film flopped, profits from underwear sales made up for box office losses. Arad dubbed his apparel-themed strategy “layering.” Here was a man who could move Underoos (and the plastic). Years later, a $525 million deal with Merrill Lynch gave Marvel its own studio. With it came the ability to sync film releases with toy rollouts to maximize merchandizing profits.

But who would lead off in the first MCU film? A 2005 focus group revealed that kids preferred playing with an Iron Man doll over any other superhero. Decision made. The movie would take in $585 million at the box office. The rest is history.

Enter Disney in 2009. Its weakest demographic was young men, and the House of Mouse needed a “delivery system for specific demographics.” Meanwhile, Marvel needed Disney’s marketing moxie, a streaming delivery service and access to financing.

Perlmutter, a notorious penny pincher, now butted heads with free-spending producers. So stingy was he that he refused to give his staff extra pencils. “Why do you need a new pencil?” he supposedly said. “There’s two inches left on that one.”

Worse, Perlmutter opposed starring roles for female superheroes. His toy industry experience had taught him boys wouldn’t buy girl-hero dolls. He refused to OK their production — but times had changed. When he blocked Black Widow toys amid other disagreements, Disney CEO Bob Iger fired him, a decision he may now regret: Perlmutter and billionaire investor Nelson Peltz are battling Iger for control of Disney.

After 15 years of multimedia products — as many as three movies and six TV series a year — audiences are “fatigued,” the Marvel-adoring authors admit. Critics blasted The Marvels, the latest flick, which premiered in November. “Scattered charm,” sighed IndieWire. “The worst MCU movie yet,” groaned the New York Post. “Disappointingly dinky,” grumbled Vulture.

Marvel has weathered crises before, but this time not even a superhero may be able to save the cinematic day. Or the plastic.

George Spencer is a freelance writer who lives in Hillsborough, North Carolina.