“God bless all of you on the good Earth.”

That’s how Apollo 8 mission commander Frank Borman ended his crew’s live, black-and-white, Christmas Eve broadcast on December 24, 1968. A global audience saw the lunar sunrise over gray images of the moon, while they heard Borman, command module pilot Jim Lovell and lunar module pilot William Anders read the first 10 verses of Genesis. Their message of hope and wonderment marked the conclusion of a grim and bloody year in which Vietnam and civil-rights woes had plagued America.

How breathtaking and spine-tingling it is more than 50 years later to hear Anders’ scratchy voice, transmitted from a distance of 238,900 lonely miles, saying, “In the beginning God created the heaven and the Earth.” Every Christmas I watch the video of this — by modern standards — primitive broadcast and share it with my family and friends. I’m dumbstruck at the brilliance of American technology, our can-do spirit and the courage of our explorers. More than that, its sketchy images and sounds leave me awed by the absolute mystery and majesty of God’s universe and our fragile and unique world.

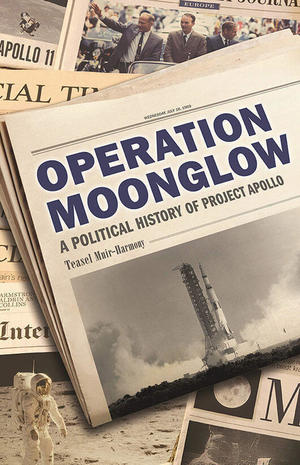

The story behind the story of the Christmas Eve broadcast is told well by Teasel Muir-Harmony ’09M.A. in her new book, Operation Moonglow: A Political History of Project Apollo. As curator of the Apollo Spacecraft Collection at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, holding graduate degrees in the history of science from Notre Dame and MIT, Muir-Harmony plays a key role shaping how the world understands space exploration. The several thousand items in the collection she oversees range from samples of space food and pressure suits to personal radiation dosimeters and toothbrushes. Her book details how the space race became the prime psychological battlefield of the Cold War‚ the literal high ground in the superpower duel between the United States and the Soviet Union.

She tells readers that while preparing for the mission, Borman fielded a call from a NASA administrator who said, “We want you to say something appropriate” on Christmas Eve.” Hey, no sweat, Borman must have thought. There’re only going to be a billion people watching. . . .

Had he been a cosmonaut, Borman might’ve been ordered to read officially prepared remarks. Instead, Muir-Harmony reveals, when he sought advice from a NASA science adviser and friend, he was told, “What you say has to be all Frank Borman. . . . Don’t forget that to use ‘one world’ or ‘peace’ more than once is to begin to lose credibility. . . . Don’t be preachy.”

Borman’s wife Susan suggested reciting the Bible verses. The crew agreed. That was that. No orders from above — except perhaps Susan’s divine inspiration.

Stories like this one make Operation Moonglow a rich and satisfying read. The title refers to President Richard Nixon’s eight-nation, post-Apollo 11 tour in autumn 1969, which he used to seek foreign leaders’ help in pushing the North Vietnamese into peace talks. Muir-Harmony’s story opens with the USSR’s surprise 1957 launch of Sputnik, which humiliated Americans and their leaders. Suddenly the world saw Russia as Earth’s technological leader. We learn that before Sputnik soared, its chief designer obsessed not over engineering details but about the shiny sphere’s appearance. He understood that on the battlegrounds of space its sights and sounds would be key to winning hearts and minds. “This ball will be exhibited in museums!” he mused. Soon people joked that when Sputnik passed over their countries, it went “beep-beep,” but when it crossed American skies it went “ha-ha.”

The U.S. fought back. Muir-Harmony describes how it created the largest-ever, sky’s-the-limit, international publicity campaign of live space telecasts (including the creation of a global network of communication stations to facilitate them), movies, exhibits, brochures and press conferences.

The PR barrage stressed democratic values, Muir-Harmony explains, especially America’s self-professed openness and its pursuit of space goals “for all mankind.” As a result, colossal foreign crowds greeted America’s Mercury and Gemini capsules, whereas the Soviets kept their landings under wraps.

The naming of space capsules reflected the down-home way Americans did things, even for events of great import such as the first American orbital spaceflight in 1962. “John Glenn chose the name Friendship 7 with help from his children. What they wanted to express was the way the U.S. felt about the world. There was a lot of hope the publicity would inspire the need for peace and that we all live on Earth in a global community,” Muir-Harmony told me in a phone call.

Her book describes global tours by handsome and well-rehearsed astronauts with their picture-perfect wives, designed to distract the world from America’s domestic problems with civil rights violence and, later, antiwar protests. The campaign succeeded. “From Cape Kennedy not even a white mouse can be launched without the nation and the world learning about it a few minutes later,” gushed an Austrian newspaper in 1965.

Muir-Harmony marvels at the “astro-graffiti” on the walls of the Apollo 11 command module, jottings that include a calendar and technical scribbles. Her favorite example was written by Mike Collins, the command module pilot aboard Apollo 11. “He wrote almost an ode to it,” she says. Collins’ neat cursive script reads “Spacecraft 107 — alias Apollo 11 alias ‘Columbia.’ The Best Ship to Come Down the Line. God Bless Her.”

Apollo 8 had an even more mind-bending impact on “the good Earth” than its Christmas Eve broadcast. While in lunar orbit, the crew took many photos. NASA dubbed one of them “Earthrise.” The color image changed human consciousness. It shows the upper half of our mostly blue planet, the Atlantic and Pacific oceans draped by swirls of white clouds. From Earth’s smooth, southern, crescent edge, Brazil peeks out of the shadows. Our world hangs like a Christmas ornament over the dead moonscape, a gift of life in the infinite void.

Nothing like this had ever been seen before. (Muir-Harmony reveals that NASA rotated the photograph 90 degrees to make it more logical to Earthbound viewers by putting the moon at the bottom of the frame.) The photo ran on the front pages of newspapers everywhere. World leaders expressed astonishment and awe. North Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh even wrote a letter to President Johnson saying so. America’s PR effort had paid off: We had wanted our space efforts to emphasize unity for all humanity. We succeeded.

As Apollo 8 returned, The New York Times published an essay on its front page by poet Archibald MacLeish, who captured the meaning of the image: “To see the earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold — brothers who know now they are truly brothers.”

In 2004, the Mars Rover took the first-ever photo of Earth from the surface of another planet. At daybreak on Mars, our world appears to be a bright star in the heavens. It is a humbling image, but it’s also good to know that we glow even from afar. One day, possibly in our lifetimes, our Martian brothers will look up and smile, remembering the warm mother world where human life began.

George Spencer is a freelance writer based in Hillsborough, North Carolina.