Two Americas. It’s become customary to think of ourselves as a divided people, at least since John Edwards’ stump speech in the 2004 race for the Democratic presidential nomination when he lumped us into haves and have-nots. But thanks to author Susan Cain, I’m beginning to think our great divide isn’t economic. Nor is it black on white, churchgoers and non-churchgoers, or red against blue that truly polarizes us. It ain’t even Mars versus Venus.

It’s personality. It’s the thin, wobbly and contorted line that divides you extroverts from us introverts. But here’s some good news: this social gap need not doom us to perpetual conflict.

As a young professional, Cain was your classic soft-spoken, mild-mannered introvert. She hated the spotlight. She was a Wall Street attorney when she realized the same personality traits that made her want to run screaming out of hardball negotiations could also help her prevail over her clients’ alpha-dog adversaries.

So she “finally started doing what came naturally.” Her talents were less obvious but “no less formidable.” As an introvert, she prepared meticulously and usually did know more than anyone else in the room. She had a quiet but firm speaking style. She could be aggressive while seeming reasonable. And she tended to ask questions and actually listen to the answers, which she found could reveal insights no one had fully considered before.

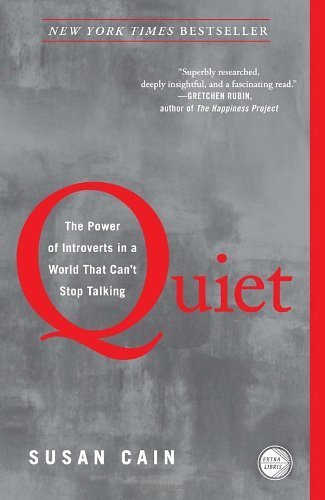

My wife picked up Cain’s 2012 bestseller, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking and told me she felt that after 14 years of marriage she’d finally read my instruction manual. So I took the 20-question self-assessment in Cain’s introduction and scored a solid 18.

The rest of the book helped me understand why I feel like such a repressed, tongue-tied lunatic so much of the time and what I can do about it. My trouble, and the challenge for the one-third to one-half of my fellow Americans who share my preferences for solitude, contemplation, thinking before we speak and deep-diving creativity over brainstorming sessions and group work, is that the cultural deck is stacked against us. As Cain points out, “Americans are some of the most extroverted people on earth.” Further, “many of the most important institutions of contemporary life are designed for those who enjoy group projects and high levels of stimulation.”

We place ultimate value on personality. We idealize extroversion and extol cool. We prize charismatic leaders who rise to power mainly because their ideas emerge the loudest and fastest. We put workers in one-size-fits-all, open-office cube farms and expect uniformly heroic productivity.

This world may work for most of us, but surely not for all of us — to everyone’s loss. The hard-to-define line dividing extroverts from introverts has mainly to do with the amount of stimulation we need to function at our best.

Cain’s book cuts through the incredible mountain of brain science and social science active on these problems and visits places I’m just so grateful I didn’t have to. So I have a better understanding of what was shaking in my amygdala and frontal cortex the day they took our offices and doors away here in Grace Hall. And I know what a Tony Robbins empowerment seminar is like from Cain’s reporting, so I need not hand over my money in the hopes that acting like something I’m not will help me be more successful.

Best of all, my wife and I now have strategies for attending and throwing dinner parties that satisfy both her extroverted needs and my introverted ones.

Cain is no revolutionary. Quiet is not a manifesto for the creation of an introverts’ utopia. Instead, it is a call for balance — a recognition that warrior kings and queens have always needed their priestly advisers, that the wild West needs the ethereal East, that society needed both the “timid” Rosa Parks and the “bold” Martin Luther King Jr. to solve one of the great problems of the 20th century.

The fact is that while we introverts need you extroverts to know we have a lot to offer if you’ll only let us get a word in, we also need you to keep our work and play from lapsing into a snoozefest.

John Nagy is an introverted associate editor of this magazine. He could also be a plenty loud, ass-kicking, longhaired Southern rock-and-roller if you just put an electric guitar in his hands. And he’s never even had a lesson.