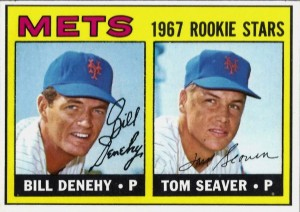

Of all the baseball cards in my vintage collection, the cruelest are those of “rookie stars.”

The players shown on those cards of yesteryear were chosen by the Topps Co. because they were youngsters of great promise. A 1967 Mets Rookie Stars card, for example, shows a 22-year-old Tom Seaver, who later pitched in the major leagues for 20 years, earned 311 victories and was elected to the Hall of Fame the first year he was on the ballot.

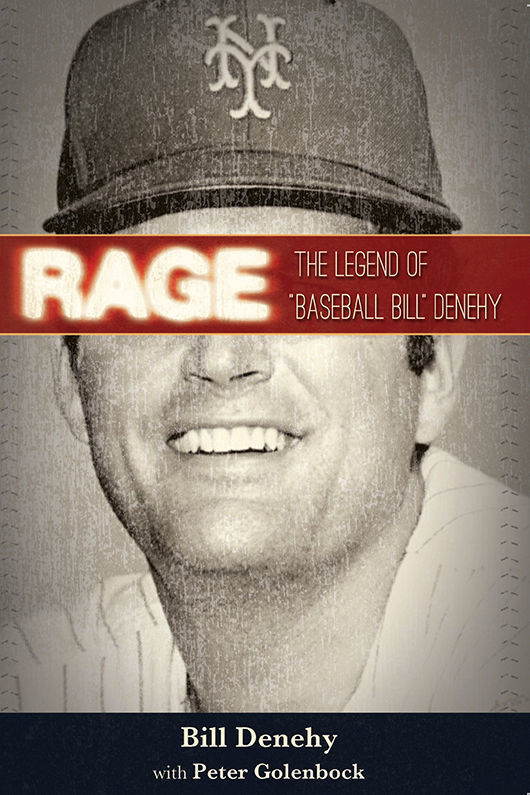

Another pitcher’s face shares that card. It is Bill Denehy, author of Rage, a 2014 memoir chronicling a life that went in the opposite direction from Seaver’s.

Denehy’s career lasted bits and pieces of three seasons with three teams, and his win-loss line was 1-10. Mainly, he offered Mets, Senators and Tigers fans some memorable opportunities to boo loudly.

Baseball is a sport where the numbers always are against you. In most years, not even the best players from your high school team will sign to play in the minor leagues. If they do, about 63 percent will never rise higher than Class A ball. Their dreams die in cities like Beloit, Wisconsin, and Batavia, Illinois.

According to the Baseball Reference website, some 19,429 men have earned major league experience since 1871. Only 226 of them played well enough, like Seaver, to join the Hall of Fame.

Among the 18,957 lesser men, Denehy stands out. His descent was cataclysmic.

One month into his major league career, in the fourth inning of a game against the San Francisco Giants, he doubled over in pain after firing a third-strike slider past Willie Mays.

“The excruciating pain was right behind my shoulder, where the triceps tendon attaches,” he writes. “It’s part of what’s now known as the rotator cuff.”

Nowadays, a pitcher would undergo Tommy John surgery, sit out a year and come back just as strong. But in 1967, the standard treatment included a little rest, an occasional cortisone shot and maybe a slight change in your pitching motion so your arm wouldn’t hurt as much.

Denehy chose other forms of medication as well, which led to alcoholism and drug addiction. After his vagabond baseball career ended, he missed the euphoria of striking out hitters like Mays. He was selling cars for a living and was in an unhappy marriage when he found his alternative.

“Cocaine gave me a feeling of exhilaration and a feeling of superiority to the point where I felt I could jump off a building and fly. . . . Eventually, I went completely crazy.”

Readers won’t be surprised. By this point in the book, Denehy has described the out-of-control temper, even when sober, that made most baseball executives shy away from giving him a second, third or fourth chance. He was prone to violence on the diamond, the clubhouse, in bars and at home.

The illegal drugs, alcohol and cortisone shots basically kicked down the demon door that had helped Denehy approximate a decent human being.

Books like these usually fail because the writer is seeking sympathy or has a scapegoat in mind. That’s why it was so important that he hooked himself up with the best baseball biographer in the business. Peter Golenbock is best known for his Bronx Zoo collaboration with New York Yankees reliever Sparky Lyle, but he’s also written for Pete Rose, Hank Aaron, Billy Martin and others.

Golenbock’s books are the sort that have you staying awake for one more chapter, even when it’s 2 a.m. He also crafted a version of Denehy able to own up to his mistakes.

Without claiming so, this story isn’t much different from the best in American literature. In Denehy, you can almost see F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby trying to impress Daisy Buchanan with his expensive shirts “piled like bricks in stacks a dozen high.”

At its core, like Gatsby’s shirts, playing baseball shows a yearning for love and acceptance. For that reason, many of us would have given our right arm for a chance to sneak a slider past Willie Mays.

And this is especially illuminating to those of us who are past our prime. The Denehy/Seaver rookie card reminds me of those employee ID card photos taken when we showed up with our eager faces, shiny shoes and sharp pencils — unaware that we, too, were on our way to our profession’s equivalent of a 1-10 win-loss line.

Ken Bradford is a freelance writer and a former reporter and editor at the South Bend Tribune.