Roald Dahl, the author of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and other masterworks like The Witches and The BFG, knew what his pint-sized readership craved. “They love being spooked. They love suspense. They love action. They love ghosts. They love the finding of treasure. They love chocolates and toys and money. They love magic,” said this storyteller supreme.

At six-foot-six, Dahl could joke, “I’m a perfectly ordinary fellow.” But there was nothing ordinary about him. When he died in 1990 at the age of 74, he was the world’s most popular children’s author. In 2021, Netflix purchased the rights to his works for a reported half-billion dollars.

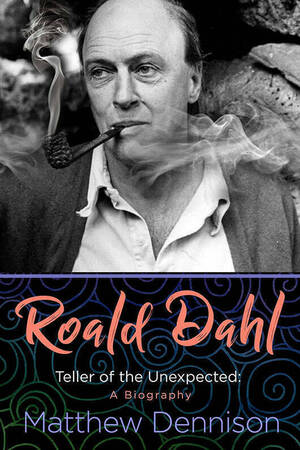

Roald Dahl: Teller of the Unexpected, a new work by literary biographer Matthew Dennison, reveals a man of strong contrasts. “I like villains to be terrible and good people to be very good,” Dahl once said.

Like other literary titans — Dickens and Kipling come to mind — he knew suffering. So it was with little Roald. His father, a butcher, died in 1920 when Roald was three, his heart broken by the sudden death of his 7-year-old daughter Astri from appendicitis. Dahl’s mother, who had “a stern lack of sentiment,” according to Dennison, sent him to a local private school. (To her credit, she also told him Norwegian folk tales about witches and dark forests.)

She withdrew him at age 11 after discovering her son had been brutally caned. In his autobiography, Boy, Dahl wrote the tears from the thrashing “poured down your cheeks in streams and dripped on the carpet.” His mother then packed him off to boarding school. He was caned there, too.

If Boy is to be believed — and why shouldn’t it be? — the first caning came as as punishment for a misdeed that revealed the lad’s dark imagination. An old woman with “a mouth as sour as a green gooseberry” ran the local candy store. When she angered him, Roald chanced on a dead mouse and stuffed it in a sweets jar so her fingers could stumble on its squishy remains.

The origins of Willy Wonka may be traced to Dahl’s love of chocolate, something not even the severest punishment could quench. At Dahl’s boarding school, thanks to an arrangement with Cadbury’s, each child received a small brown box containing eight bars. He dreamed of inventing new chocolates. Working in London as a young adult, he saved the silvery foil from the bars he ate every day after lunch, and he wrapped them around each other until they were as big as a tennis ball.

Dahl also had a sweet tooth for all things ghastly. His short stories and scripts won him prestige long before he turned to children’s fiction. In “Neck,” a woman dies after being unable to free her head from a hole in a Henry Moore sculpture. In “Lamb to the Slaughter,” which Alfred Hitchcock directed for his long-running TV anthology show, a wife brains her husband with a frozen leg of lamb. She then roasts it and feeds it to the witless police.

Dahl’s life had the makings of movie. A Royal Air Force fighter pilot during World War II, he crashed in the Libyan desert and spent weeks blind and immobile while recovering in the hospital. Back in the air, he downed three German fighters. Later, assigned as a military attaché in Washington, D.C., he doubled as a gentleman spy. After spending the weekend at Hyde Park with FDR, he promptly filed a 10-page report to his embassy. Deemed the most attractive man in town by an admirer, he bedded cosmetics queen Elizabeth Arden and author Clare Boothe Luce.

Novelist C.S. Forester, creator of Horatio Hornblower, helped launch his writing career. Walt Disney nearly made his first children’s storybook into a wartime movie. Later, Dahl married movie star Patricia Neal and penned screenplays for two very different Ian Fleming tales: You Only Live Twice and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

Life, nonetheless, was hard for Dahl. An early play and a novel for adults both tanked. He drank too much. And he made other questionable decisions. When Neal suffered a severe stroke in 1965, he put her through a punishing rehabilitation regime — “the way one trains a dog,” a friend observed. Though Neal hated him for it, she would admit, “He really did do a wondrous job. He was a very good man.” Later, Dahl had an 11-year affair with one of her assistants, whom he subsequently married.

By then, far worse things had happened, as they might have in one of his stories. In 1960, a careening taxi had flung his infant son Theo against a bus, crushing his skull. Shunts failed to drain his cerebral fluid. Doctors gave up. Indomitable, Dahl brought together a pediatric neurosurgeon and a toymaker, who created the Wade-Dahl-Till valve, which saved Theo’s life. Dahl made sure it was marketed on a nonprofit basis.

All his life, Dahl said, “the key thing was not to get depressed and feel sorry for yourself. You had to rise to the challenge. Do something. Anything was better than nothing.” Alas, when his daughter Olivia died of measles in 1962 at age 7, he was bereft. “Life isn’t beautiful and sentimental and clear,” he told a former classmate. “It’s full of foul things and horrid people.”

No wonder, writes Dennison, that Dahl’s “darkest fictions portray without regret a world of cruelty, cynicism, misanthropy, and caprice. . . . [Yet he] provided his underdog heroes with the mechanisms for dealing with these emotions and the circumstances from which they might emerge.”

Late in his life, charges of anti-Semitism arose, especially when Dahl railed against Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon. “Even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on [the Jews] for no reason,” the New Statesman quoted him as saying.

Dahl reserved special venom for editors, yet to this day they meddle with his prose. Earlier this year, his publisher sparked furor from fans and luminaries like Salman Rushdie when it announced it would release bowdlerized versions of his classics. Words like fat, ugly, crazy and mad were cut from every book. (The publisher then announced it would offer the original texts under another imprint.)

One wonders how volcanic Dahl’s reaction would have been were he alive.

Dahl, like the rest of us, had many flaws, but unlike most of us, he had a wizardly imagination that made millions happy. His often-orphaned heroes always defeated bullies. “There are very few messages in these books of mine,” Dahl demurred. “They are there simply to turn the child into a reader of books.”

His favorite was The BFG, in which the orphan Sophie battles giants. Perhaps Dahl was himself a Big Friendly Giant who captured and bottled dreams like the BFG he imagined into being. Like his kindly character, the author might also have said, “I am hearing all the secret whisperings of the world.”

George Spencer is a freelance writer who lives in Hillsborough, North Carolina.