Sometimes history is personal. Take, for example, the Battle of Gettysburg. My great-grandfather Samuel Moseley fought there. He was a captain in the 21st Regiment, Virginia Infantry. Writing to his mother on July 17, 1863, two weeks after the battle, Moseley recalled it as “one of the hardest contested battles of the war. . . . I do believe it would have been better that Richmond had fallen, no telling now when this war will stop.”

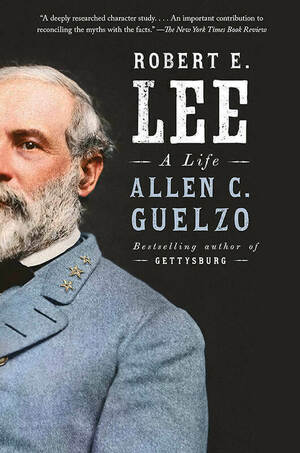

Robert E. Lee, the commanding general of the Army of Northern Virginia, had brought my ancestor to that battlefield — and that conclusion. I had never thought much about the more famous man, but when I learned that Princeton historian Allen Guelzo had produced a new biography, Robert E. Lee: A Life, I picked it up, seeking insight into who he was.

Why did Lee abandon his commission in the United States Army and become a traitor? That is how Guelzo, the author of more than 10 books on Lincoln, the Civil War and Reconstruction, sees Lee — as a traitor. His book begins with a question: “How do you write the biography of someone who commits treason?”

To the modern mind, what’s curious about Lee is why he has been so widely admired. Southerners in days past called him “the marble man.” He was dignified, the model of propriety. Even Lincoln had good things to say about him. When shown a photograph of his adversary, Lincoln said Lee’s “is a good face; it is the face of a noble, noble, brave man.” Stoic in defeat, Lee soon distanced himself from the emerging Ku Klux Klan.

Nothing is so deceiving as a beautiful surface, even if it is marble, and Guelzo finds Lee instead to be a hollow man with feet of clay, a leader of men who never recovered from childhood scars. When Robert was six, his father, the Revolutionary War hero “Light-Horse” Harry Lee, all but abandoned his family. Young Robert became devoted to his mother and assumed a spotless persona. He famously earned no demerits at West Point, graduating second in his class in 1829. (Years later, the flamboyant George Custer, a terrible student, tallied a record 726.)

Lee became not a cavalry officer but a military engineer. He liked obeying tidy laws. For the next 25 years he carried out coastal engineering projects. According to Guelzo, Lee, thanks to his childhood wounds, sought financial security, not the roar of cannons.

He was not bloodthirsty, but he was brave. During the Mexican-American War, from 1846 to ’48, his superior, General Winfield Scott, praised his courage. But as Lee wrote to one of his sons at the time, “You have no idea what a horrible sight a battlefield is.” Perhaps the only enduring thing he ever said came during a Civil War battle: “It is well that this is so terrible, [lest] we should grow too fond of it.”

If not for military glory, surely Lee turned against his country to defend slavery? Not really. He did inherit 42 slaves in 1857 when he became executor of his father-in-law’s 1,100-acre hilltop estate in Arlington, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. But Guelzo makes clear that owning humans nauseated Lee — especially after he ordered the whipping of three escaped slaves who had been returned to him. He stripped one of them — a woman — and delivered 39 lashes to her back. The atrocity made its way into a New York newspaper, an article to which Lee refused to reply. Guelzo writes: “It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that when his fury had cooled, he was sickened at himself, as much for the damage done to his own self-image as for the cruelty inflicted on the three fugitives.”

The aging officer famously turned down Lincoln’s offer in April 1861 to command the Union Army. Instead, he sided with the South, Guelzo argues, not to defend states’ rights or slavery but for a more astonishing reason — to keep the Arlington property in his family’s hands, safe from confiscation. “The property belonging to my children; all they possess lies in Virginia,” Lee told Scott. “They will be ruined if they do not go with their State. I cannot raise my hand against my children.” Unlike his father, Robert E. Lee would not abandon his family.

Lincoln thought deeply for years about slavery and came to the right conclusion. Lee, not so much, according to Guelzo. Instead, he accepted things as they were. That was his tragedy. “Indifference to slavery is not quite the same thing as its active embrace and promotion, but not by much,” Guelzo writes.

In the end, Guelzo, a lifelong Christian, asks his readers to have compassion for Lee, but not necessarily to forgive him. “Mercy — or at least a nolle prosequi — may, perhaps, be the most appropriate conclusion to the crime — and the glory — of Robert E. Lee after all,” he writes.

If Lee is worthy of admiration, it would be for his gifts as a military strategist. He thought the Confederates’ only hope of winning lay in breaking the Union’s will to fight, and that the best way to do that would be to deliver a shattering blow to the North on its own soil. That’s why he led his army to Gettysburg. Months before that onslaught, he even predicted that the Pennsylvania hamlet tucked just across the Maryland border would be where it would happen.

This “great battle,” he wrote, would “attain far more decisive results than could be hoped for from a like advantage in Virginia” and would achieve “the recognition of our independence,” because “the Federal army, if defeated . . . would be seriously disorganized, . . . and it would very likely cause the fall of Washington city and the flight of the Federal government.”

Of course, after their defeat at Gettysburg, Southern armies never again threatened the North. It was only a matter of time before the Union’s greater resources and relentless attacks overwhelmed the breakaway states.

After the war, and before he died from a stroke, the exhausted Lee spent five productive years reviving the fortunes of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, now Washington and Lee University.

As for my great-grandfather Samuel, he held out little hope for Confederate prospects after Gettysburg. “I never care about going in Maryland or Pensy again,” he wrote in that same letter to his mother, “the people were very anxious for peace in those states, but I do not see how it can be made until old Abe’s time is out. It is a beautiful country & there seems as if no war was going on, from their fine crops & things so clean. How is the home guard getting on, all of them had better come out to defend their homes, for they can do nothing where they are.”

Less than a year later, at the Battle of Monocacy in Maryland, Samuel was shot in the left forearm. He was held as a prisoner of war until the end of February 1865. His arm left useless for physical labor, he returned home to central Virginia, ran the Buckingham Hotel and became a deputy sheriff. A history of local veterans says he played the banjo well and was an acclaimed musician.

In 1908, he played and sang wartime songs at the unveiling of the Buckingham Confederate Monument, an obelisk whose inscription dedicates it to the “heroism and devotion” of local soldiers. Buckingham is a small, quiet place and is unlikely to see any monument removals similar to those in nearby Richmond and Charlottesville. My ancestor took his stand, like Lee, and lived and died in Dixie. What he thought about slavery — and the lifelong harm he and others suffered from war — I will never know.

George Spencer is a freelance writer who lives in Hillsborough, North Carolina.