It’s a story as old as civilization and is still commonplace today: Tsuneno, a single woman, sets out for the big city in search of adventure and a brighter future. And things don’t go as planned.

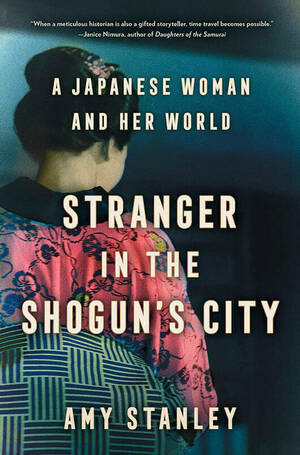

The result is Stranger in the Shogun’s City: A Japanese Woman and Her World, by Amy Stanley. The author is a professor of history at Northwestern University.

I picked up the book on a whim after reading a tweet of recommendation by Washington Post book critic Carlos Lozada ’93. With the coronavirus subsiding in our area but the pandemic by no means over, I’m not quite ready to embrace long-distance travel. For now, armchair journeys via the local library remain my satisfying substitute.

This nonfiction work, based on Stanley’s deep-dive into hundreds of period documents, is like time-traveling to 19th-century Japan before it opened its borders to visitors and changed forever.

From the first page, I was utterly engrossed. An enchanting read, Stranger in the Shogun’s City was the deserving winner of a National Book Critics Circle Award for biography in 2020 and a Pulitzer Prize finalist in biography this year.

Most works of history are based on records left behind by the rich and famous — kings and queens, capitalists, artists and others who are well known and much discussed in their day. What makes this story captivating is that Tsuneno is an ordinary woman living an ordinary life in an era when women’s lives and accomplishments didn’t get much notice. She married four times and had no children. She would be forgotten today if not for several strokes of luck.

Tsuneno’s family and their descendants kept a meticulous collection of documents, including letters, tax bills, receipts, lists of wedding gifts and death notices going back several generations. Those family papers eventually wound up in a public archive, and an archivist posted one of Tsuneno’s letters on a website.

More luck: Stanley saw the letter and was drawn in. She visited Japan to study the documents and to place them within her own deep knowledge of early modern life in that country. The result is a rich tapestry depicting Japanese life in the first half of the 19th century, particularly bustling daily life in Edo — the city that in a few short years would become Tokyo.

Tsuneno was born in 1804 into a respected family in the cold-weather country of northwestern Japan. Her father was a Buddhist temple priest in the small village of Ishigami. She was among eight children in her family who survived infancy.

She lived during the Great Peace. It had been nearly 200 years since Japan had last gone to war. Since the middle of the 17th century, the shogunate (Japan’s feudal system of governance) had barred Western traders and diplomats from Japanese soil — except for the Protestant Dutch, who weren’t intent on proselytizing.

It was in many ways a perplexing world by today’s standards. Young girls were taught to open doors as quietly as possible and to walk so their footsteps could barely be heard. Yet it was not unusual for married couples to divorce or for women to be married several times.

By some counts, nearly half of Japanese women ended up divorced from their first husbands. “Divorce was a practical solution, a safety valve for a family system where so much depended on the compatibility of young couples,” Stanley writes.

Sharp-tongued wives or disobedient workers might find themselves locked inside a wooden cage and placed on public display as a means of punishment and humiliation. “Cages were in courtyards or in front rooms, where people from the community could see that the punishment was underway. In fact, that was part of the point, to save the family’s reputation by displaying its resolve,” Stanley writes.

By the age of 12, Tsueneno entered an arranged marriage with the leader of another temple located 180 miles from her hometown. But after 15 years, the marriage ended in divorce, and Tsuneno returned home. Her family quickly found her another husband, but that marriage also ended in divorce, as did a short-lived third marriage.

In her mid-30s, Tsuneno crafted a story to tell her family then secretly set off on foot to Edo, a two-week journey. To rural people of that era, Edo symbolized everything sophisticated and fashionable. In the city, with no money and just one robe, Tsuneno settled into a typical “three-mat” room in a tenement on an alley. The room was only six feet wide and nine feet long.

She found work as a maid in the household of a samurai, but money was always tight. Tsuneno wrote letters home, pleading with her brother to send more robes and other supplies. “I want to get out of this room,” she wrote home, “but unless something changes I’ll never be able to escape.” Great value was placed on clothing and sewing in that era of Japanese culture — the type of fabric, the cut of a robe, the quality of the stitching and how easily the pieces could be taken apart for washing.

Stanley paints a vivid picture of Edo: the narrow streets, produce markets, kimono shops, temples, the theater district and numerous fire towers, which guarded against the blazes that regularly engulfed the wooden city. In stores, clerks took orders and clicked their abacuses to figure receipts. Peddlers, musicians, and tofu and charcoal carriers crowded the thoroughfares.

At the time, samurai and their families made up half of Edo’s population of about 1.2 million residents. But with the Great Peace, it had been generations since this elite warrior class had been called upon to fight.

Whether for love or economic security, Tsuneno soon found another husband. By this time, her family was exasperated and embarrassed by her. After this fourth marriage, her elder brother wrote a letter of blunt warning to the groom: “As you know, she’s a very selfish person, so please return her to us if things don’t go well.”

Tsuneno had no way of knowing it, but she was living her latter days on the precipice of a dramatic moment in history. As her story drew to a close, Commodore Matthew Perry was aboard a ship steaming to Japan, assigned by U.S. President Millard Fillmore to force open Japanese ports to American trade.

The gambit succeeded. Within a few years, the last shogun would fall from power, Edo would become Tokyo and life in Japan would be transformed. Lucky for us, Tsuneno and her family left the records that helped Stanley paint such an evocative portrait of Japanese life in those “before times.”

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.