When I first read Steven Nightingale’s 1996 bestselling novel, The Lost Coast, I was impressed by his frolicking, fun word play. My, how that guy writes with alacrity! I thought. The author was rightly compared at the time to authors such as Tom Robbins and Ken Kesey. The novel’s characters, however, lacked depth; they said and did stereotypical things — funny, clever, and fantastical things, to be sure — but they were shallow. I just couldn’t crawl into that book’s world, or even find a real plot. A friend referred to it as “a flashy tour de force” that goes nowhere.

Much has changed in Nightingale’s writing style over the past 20 years. He has continued to hone and perfect his craft, publishing another novel, six books of sonnets, and a book of nonfiction essays titled Granada: A Pomegranate in the Hand of God.

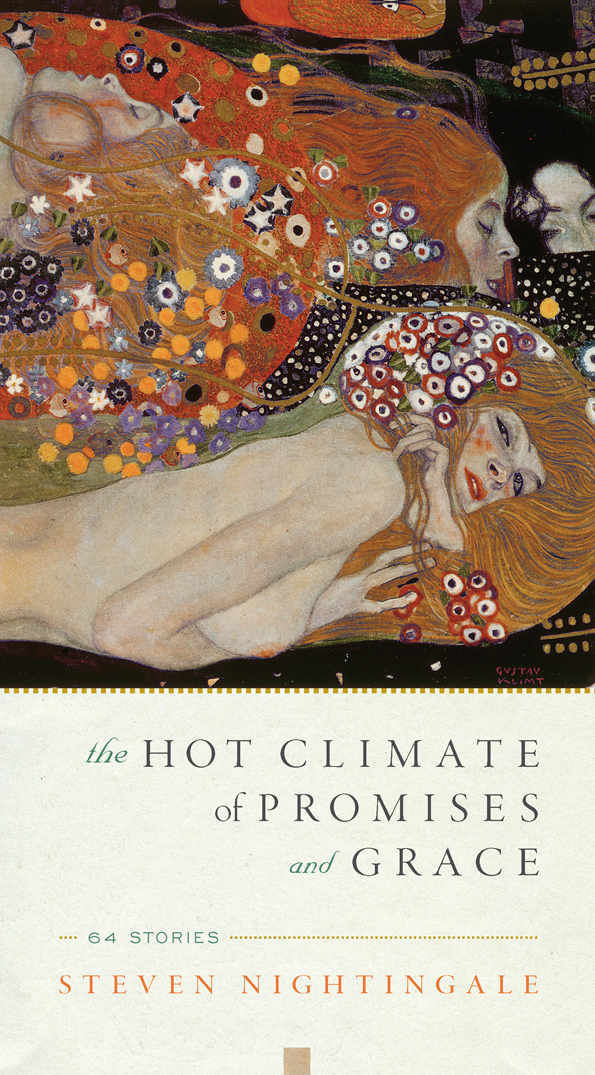

Today, Nightingale has matured into a master wordsmith and lyricist. His latest work, The Hot Climate of Promises and Grace, gives us prose that flows like poetry, fantasy that is so magical and rich it is believable, and an enchanted world the reader wants to enter and inhabit. If, like me, you sometimes need just such a place in which to harbor your weary life, to be regenerated by the beauty of well-wrought phrases and sentences, this is a book for you (“cut loose lyricism,” Nightingale calls his writing style; and it is apt).

Hot Climate is composed of 64 discrete fables about, or as told by, women and girls who are attuned to a sacred reality that permeates the cosmos: in the feel of pebbles in a stream, the angle of sunlight through a window, the flowing of water, the rich aroma of fresh bread, the wonderment of stars, and of a man and woman making sweet love. Each fable is short, from two to four pages, and reminds the reader of the simple but beguiling tales of the Sufis, or the charmed stories of the Desert Fathers of early Christendom. The book is not explicitly religious, as these other works are, but it is deeply spiritual, revealing the hidden spiritual treasure incarnate throughout the ordinary world, often in plain sight, for those who will look.

Among these fables is “The Bank of Days,” in which the reader learns of a new sort of bank that “does not accept deposits of money, but only of people’s days.” When someone has lived a day that is especially amusing, instructive, or beautiful, they may go to the bank and “deposit this day into the common account.” There are no individual accounts at this bank because “days are not the property of anyone, but belong to the commonwealth of our experience.” A certain woman, say, might seek a loan of some remarkable day — for example, a day “that has in it the sightings of many falcons, who fall out of the sky with a sure, able, lovely swiftness and silence.” The way the falcons glide “high and still,” with “wings spread, facing into the wind,” teaches this woman how “to situate herself, to teach a way of consideration, of reflection, a habit of steadiness — so that she learns, once and for all, how to keep the whole in view.” The woman then adds her experience to that day, which becomes changed and enriched, and repays it to the bank so that another may borrow it and add to its value. Such, says our author, wittily, “are the wonders of compound interest.”

The reader might find three or four tales in Hot Climate that don’t please aesthetically, as I did, but the story “What We Mean by Bread; and by Sacrament” will not be one of them. If you buy bread, the story’s unnamed female character discovers, you get only a loaf, but when you “say bread, you get more than a loaf. You get noon light on the wheat fields, the quickness of foxes wandering in the adjoining forest, the hope for the harvest, the history of stories in the hands of the baker; you get all that bread’s venerable associations with heaven, any one of a thousand celebrations at table; you get a living thing that, right there in front of you, may come into amorous concord with the wine and cheese” also at that table. You also get shared thankfulness and many other good things, all of which become “part of what will be meant always . . . everywhere . . . each moment in the world, whenever someone says — bread.”

In other stories we meet a Carpenter of the Heart, learn about the Astrophysics of Children, and hear from a Woman Who Writes About the King She Loves: “Once upon a time there was a man who wanted to be king, and because of his hard work, and whole heart, by the rigor of his mind and the beauty of his sentences, he was indeed proclaimed king.” Beautiful sentences and lyrical prose do indeed elevate us to royalty of mind and spirit. Therefore, dear friends, do go out and buy this lovely book. It will reward you with days of pleasure that you can then deposit into the Bank of Days.

Ken Garcia, an award-winning author, has recently published a spiritual memoir, Pilgrim River. This review continues his series of “Overlooked Gems,” books so beautiful they should be bestsellers but have been overlooked in the trendy swelter of commercial book marketing. Previous reviews in the series include Nancy Nordenson’s Finding Livelihood: A Progress of Work and Leisure, and Amy Andrews and Jessica Mesman Griffith’s Love & Salt: A Spiritual Friendship Shared in Letters.