I have always been interested in the relationship Joseph P. Kennedy had with Father John J. Cavanaugh, CSC, president of Notre Dame from 1946 to ’52. In 1951, 90 cadets were expelled from West Point for cheating. Kennedy was on his yacht discussing the matter with Father Cavanaugh and asked: “What would it cost to send all these young fellows through Notre Dame?” The priest quickly calculated that it would run “about a half million dollars” ($12.4 million in today’s purchasing power). Joe offered to pay all their expenses at Notre Dame, on the conditions that his support would be anonymous and that none of the cadets could participate in intercollegiate athletics, lest “people think that Notre Dame’s benefactor is trying to buy athletes for the university.” Thirteen of the cadets registered and 12 graduated — at which time they were told who their benefactor was.

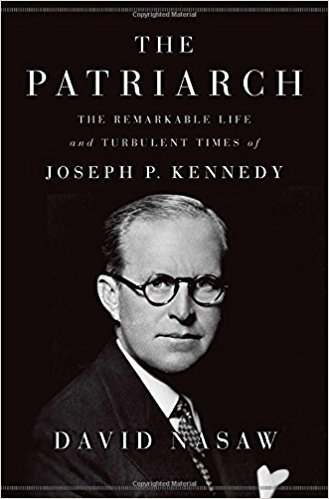

So I was pleased to pick up The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy and find this story. It is a special challenge to write about a man of such breathtaking success, glaring flaws and searing tragedy, but David Nasaw’s definitive biography accomplished that.

Nasaw was given unique access to all the papers in the Joseph P. Kennedy collection at the Kennedy Library in Boston. There were times during my reading that I would have opted for an abridged version of the book. Ultimately, however, every moment spent with this splendid biography provided real dividends.

Nasaw provides a detailed accounting of Kennedy’s business successes. At 25, he became the youngest bank president in the country. During the 1920s he moved to Hollywood as head of a small, debt-ridden movie studio. After a few years of applying “a banker’s good sense to making pictures,” he was able to retire with millions of dollars in stock options.

Then to New York and Wall Street, where Joe anticipated the stock market crash of 1929 and made money selling failing stocks short. By age 40, he was one of the wealthiest men in America — and Nasaw maintains that there is no evidence whatsoever that he engaged in illegal bootlegging during Prohibition.

After supporting Franklin Roosevelt’s successful presidential campaign in 1932, Joe was rewarded with the task of creating and chairing the Securities and Exchange Commission. It was a controversial appointment, but his performance was met with widespread praise. In 1937, he served as the chairman of the Maritime Commission, and by the late 1930s, Joe was prominently mentioned as a possible presidential candidate.

Nasaw describes Kennedy as an “active, loving, attentive, somewhat intrusive father.” He corresponded faithfully with all of his children when he was not at home (most of the time). However, he was a far cry from a model husband. He had affairs with countless women, the most notorious of these with actress Gloria Swanson, whom he often invited to be with him on family occasions that included his wife, Rose.

The pinnacle of Joe Kennedy’s remarkable trajectory of success came in 1939 when FDR named him ambassador to the Court of St. James — the first Irish American to be accorded that honor. At this point, however, his faults and limitations became manifest. By background and disposition, Kennedy was unprepared for a diplomatic position. Nasaw recounts that “he violated State Department directives with impunity” as Kennedy carried on his own personal crusade to keep America out of the war.

Kennedy offered unquestioning support for Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement policies. In fact, he actually expressed disappointment that the Germans did not prevail in the Battle of Britain because he felt it only delayed Hitler’s ultimate victory. He resigned in December 1940, his views no longer respected, and never again entered public service. Even after the war, however, he persisted in his Cassandra-like isolationism, opposing the creation of NATO and the Marshall Plan.

Throughout Joe’s life, his primary focus was on the future success of his nine children. His stated purpose, early in his business career, was to make so much money that his children could devote their lives to public service. In this regard, his success was monumental. Three of his sons became U.S. senators, one became president. His daughter Eunice changed the way special needs children were viewed and treated throughout the world.

Ultimately Joseph Kennedy’s life was one of overwhelming tragedy. His first and most adored son, Joe Jr., was killed when his airplane targeting a massive Nazi underground military complex detonated in mid-air. Kick, a daughter for whom he had a special affection, was killed in an air crash in France as her father waited to greet her in Paris. Then there was the massive stroke he suffered less than a year after watching his son be sworn in as president. The stroke left him dependent on the care of others for the rest of his life. It was in this condition that he learned — the news was withheld from him as long as possible — of his son John’s assassination in 1963 and of Robert’s murder in l968. Left speechless, he was never able to fully articulate the profound grief these tragedies surely caused him. A year and a half after hearing the news of Bobby’s death, Joseph Kennedy died at age 81.

The Kennedys (especially John Kennedy) and Notre Dame both exerted powerful influences on my life. In The Patriarch, Nasaw provides the great service of detailing the origins of the Kennedy political juggernaut as well as the price Joe Kennedy paid for it. An added benefit of the book for me were those few but fascinating cases where the histories of both the Kennedys and Notre Dame intertwine.

Tom Scanlon is the founder and president of Benchmarks, a Washington, D.C., consulting firm. He was among the first young Americans to serve overseas in President John F. Kennedy’s Peace Corps.