All but the lucky learn early that life is a plotted story only in art and imagination.

When my wife was diagnosed with cancer, family and friends were surprised that someone who lived in her deliberately healthy manner could have a life-threatening illness in her 50s. It was a shock to learn yet again that mortality and self-determination are incompatible dance partners, although that didn’t stop several well-meaning and loving souls from urging on her a new plot in which she would save herself by eschewing sugar, swallowing vitamin supplements or embracing faith healers. She herself was simply content to enjoy as best she could whatever might be left of her life.

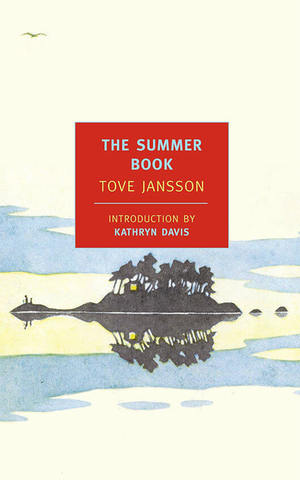

I was reminded of all of this as I finished reading The Summer Book, a refreshingly plotless 1972 novel by Tove Jansson.

In a gentle voice, The Summer Book considers an elderly woman and her 6-year-old granddaughter as together they engage the blessings and frights of a summer on an island in the Gulf of Finland. Small conflicts and other dramas come and go, but as summer ends, the personalities of the grandmother and the girl are largely unchanged, as are their lives.

For that I am grateful. I like exciting plots and need stories as much as the next person, including the tenuous comfort of pat stories, but every so often I encounter a good novel — James Agee’s A Death in the Family comes to mind — that has been rendered plotless. Reading The Summer Book, I recognize that in this plotless existence I am in the company of countless bewildered others, who, as the grandmother says, would nonetheless like “to stay for a while.”

The grandmother is not well. She has spells of vertigo and breathlessness and unpredictable periods of fatigue that compel her to nap often, sometimes on turf or sand when she has been exploring the island with her granddaughter, Sophia. Jansson maintains a seawall against sentimentality, and yet the pressing mortality of the grandmother is poignant because she and Sophia are nearly constant companions. As if in an aside, Jansson writes on page 9, “Sophia woke up and remembered that they had come back to the island and that she had a bed to herself because her mother was dead.” The next sentence is about woodstove flames and boots hung to dry. We never learn the cause of the mother’s death. It doesn’t seem to matter; death is death.

Sophia’s father sets rules for his daughter and mother but is largely withdrawn from family life, like a demigod of the Deists. He goes off to a boozy party, tends a flower garden without joy and occasionally ventures out to net fish, but we are told repeatedly, “Papa sat working at his desk.” What manner of work, we don’t know. His mother and daughter are the two major characters of the novel in part because, in more than a single sense, they are alive. Then again, maybe at his desk, Papa is writing their story.

Sophia is a little too precocious to be an entirely credible character, but she is so likable that I can suspend disbelief — something I never could do for J.D. Salinger’s child geniuses. She and her grandmother construct a miniature Venice, write a book about angleworms, adopt cats, argue about God and hell, and also cheat at cards, disobey several of Papa’s rules, sing a scatological ditty and break into a house because the grandmother is offended by the “NO TRESPASSING” sign. The child takes care of the grandmother just as much as the grandmother does her. When Papa is planning to leave the island for a few days, he arranges, without consulting his mother, for his family to stay in the care of other people. Depressed by his supposition that she is incapable of caring for herself, his mother withdraws to her bedroom, abandoning her granddaughter, who begins to coax her out by sliding under the door a note that says, “I hate you. With warm personal wishes, Sophia.”

When I was a tutor at a Franciscan university, students sometimes stopped by my office for help with understanding a sentence of a passage from St. Bonaventure’s The Mind’s Journey Into God. It considered the meaning of the “highest good.” In the Oleg Bychkov translation, the sentence reads, “Now such a thing exists in such a way that it cannot be rightly imagined as not existing, because it is absolutely better to exist than not to exist.” I asked the students to suppose, regardless of what they actually believed, that God created the world, and asked them next, “Are you glad to be alive?” I thought I had hit upon a simple way to assist their reflection — until the day when a student, quite seriously, informed me she was unhappy to be alive. On occasion, I’ve felt that way myself, which is why I feel very fortunate to have met — if only in a novel — Jansson’s vibrant characters, Sophia and her grandmother, who, as the family prepares to depart the island at the end of summer, lies on her bed and wonders, despite the discomforts and indignities of her old age, “How can I ever leave this room?”

Mark Phillips lives in southwestern New York. He is the author of a memoir, My Father’s Cabin, and a collection of essays, Love and Hate in the Heartland, and is a frequent contributor to this magazine. His essay, “Out of the Dark,” appeared in our Spring 2021 issue.