The boss was asking what happened with the grand jury.

As his lawyer went down the list of aides who had testified, the boss asked which ones had lied. Nearly all of them had. That was good news. If your choice is between perjury and obstruction of justice, perjury is harder to prove and less likely to send you to jail, the lawyer said.

The boss then wondered aloud about the best way to hide a million dollars to pay men who didn’t want to lie. Not a problem, he was told. Ask Herb. He has plenty of cash stashed in a secret safe.

The boss was Richard Nixon, in 1973. I’m writing about him today, but I want to start with my own confession about James Joyce.

Joyce, an Irish novelist, wrote Ulysses about 100 years ago. It regularly tops the lists of best books ever written. I’ve made three serious runs at this epic book — at ages 22, 45 and 63 — but have been beaten back less than halfway through each time. My copy is about 700 pages, the writing is dense, its allusions are obscure and the rewards are too few.

Maybe I’m just not smart enough to appreciate that book, but at least I’ve tried. For me, the book is no good.

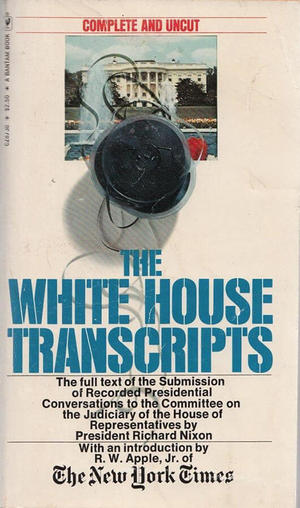

I have felt the same way about my Nixon book — the complete and uncut White House Transcripts, published in May 1974 by The New York Times. Like Ulysses, the transcripts are thick — 877 pages, with run-on sentences that seem impenetrable.

Portions of both books are a slow slog. But this time, unlike my failures with Joyce, I figured out a strategy that makes the Nixon-Watergate book work.

I need to save space here. If you don’t know the basics, Wikipedia can tell you about Nixon and the Watergate burglary of 1972.

To save his own skin, Nixon was willing to fling minor staffers into the wolf pit. Some overzealous person authorized the burglary, it was claimed. The notion was plausible. For much of 1973, it appeared the president had enough true believers that he would survive the allegations and speculations.

The transcripts did him in. A low-level aide blurted out that all conversations in the office with the president were tape-recorded. Once the recordings were transcribed, all of America could read exactly what their president had said and done.

I’ve had the Transcripts paperback for almost two-thirds of my life. I’ve moved it from Notre Dame to Hartford City to Fort Wayne to Mishawaka and to three different homes in South Bend. I’ve picked at it but never put myself in a comfy chair to read page 1, paragraph 1.

So why now?

The short version is this: In a holier-than-thou mood, I had read the 448 pages of Robert Mueller’s report on Russian meddling in the 2016 election. I didn’t want anyone — the attorney general, Rachel Maddow, Anderson Cooper or Sean Hannity — to tell me what was there.

It turned out to be easy. Half the text is footnotes or redactions, so it’s really just 250 or so pages of actual reading. Give it a try.

I now have a clear understanding of what happened in Russiagate. I also was filled with remorse for my harsh judgment of Richard Nixon these past four decades. I had allowed experts to convince me that Nixon deserved to be impeached when the raw words were available on a book on a shelf six feet from my desk.

The transcripts are easier for me to read now because I’ve decided to give Nixon a break. I give him the voice of a flawed hero, similar to Walter White of Breaking Bad or Tony Soprano. As I read, I want him to survive the mistakes he is making.

It also has helped that I have read many of Shakespeare’s major plays. When I hear Nixon now, I think of one of my favorite characters, the Scottish general Macbeth.

In Nixon’s Oval Office, the fire burns and cauldron bubbles each time an aide speaks. Like the ambitious Macbeth, Nixon is emboldened by bad advice.

Things go haywire. He finds he can’t just pile the blame on some hapless junior staffers. If he were Tony Soprano, one of his goons would take John Mitchell, Jeb Magruder and Gordon Liddy on a one-way fishing trip. Macbeth would dispatch them with his own knife. Instead, Nixon must figure out a way to convince them that they won’t mind a few years in prison.

As more advisers strut and fret, the heap of sacrificial lambs grows: Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Colson. Things get worse. One of the main characters, legal adviser John Dean, discovers a conscience and is willing to tell — in exchange for a reduced sentence — the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

Because it’s such a long book, there are dozens more “out, out, brief candle” moments than Shakespeare was allowed. I feel sorry for Nixon when he finds out about Dean’s immunity deal. We all have secrets. We know what it’s like to realize that people who believe in us will be hurt the most.

Nixon was a product of his time, just as we are of ours. He felt he needed to act tough because, unlike President Kennedy, he grew up in a world he viewed as brutal. He wouldn’t be loved so he chose to be feared.

The toughest question about Nixon’s America, and ours, was written by Hunter Thompson just before the 1972 election: “Where will it end? How low do you have to stoop in this country to be President?”

Read it here, the boss’ own sorry words. There was no depth beyond Nixon’s reach.

Ken Bradford is a freelance writer and former reporter at the South Bend Tribune.