Lyndon Johnson seemed almost like a fictional character. Or a political cartoon come to life, jowly and twangy, all outsized Texas appetites, especially for power. Every appendage appeared oversized and hyperactive, making even the most passive behavior a form of physical exertion. When people talked, a longtime ally said, Johnson “would listen at them.”

He’s easily caricatured, so brazen was his grasping, and his manner so “cornpone,” as the Hahvahds of the Kennedy administration condescended to call the vice president of the United States. Maybe you’ve heard the recording of President Johnson — let’s say, colorfully — ordering pants from Joe Haggar ’45. A real piece of work.

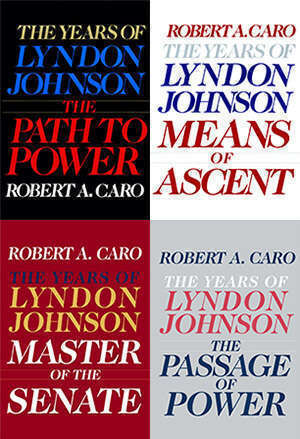

In four volumes (and counting), biographer Robert A. Caro depicts Johnson’s panoramic crassness. With scrupulous documentation, Caro portrays the relentless, cynical, even illegal accumulation of power, absent any consistent personal conviction, that defined Johnson’s public life. Using the same patient, unobtrusive marshaling of facts, Caro also illustrates Johnson’s deep, genuine compassion for the downtrodden. The rub was that he’d wield his hoarded influence on their behalf only if it served his own immediate interests.

Caro captures the contradictions of Johnson’s character that resound like clashing cymbals — loud, brash, pull-the-pillow-over-your-head kind of noise, but also, now and then, a note perfectly struck. Together the books tell the story of an almost impossibly preposterous man and, through him, offer an evocative account of the political era over which Johnson’s brass clanged.

This literary-historical project is as ambitious as it sounds, neutering book-blurb words like “comprehensive” and “exhaustive.” Caro values such deep research that he and his wife lived for nearly three years in the rural Texas Hill Country where Johnson grew up. The New York-based author saw no other way to understand the place that formed Johnson, or to earn the trust of people whose memories he needed to compile a complete portrait. And now, at age 85, Caro has acknowledged the specter of life’s ultimate deadline as he continues work on his fifth and final volume, going on 40 years since publication of the first. It’s been eight years since the fourth book, The Passage of Power, was released and won the National Book Critics Circle Award for biography and several other prestigious awards for history.

My dad had early volumes on his bookshelf, I remember, but to me they were indistinguishable from his other biographical doorstops. Even the covers are all text. I like reading history, though, and given the accolades attached to these, I thought eventually I’d get around to trying them on for size. Now I’ve read all four. Not one right after the other, but here and there over several years, the latest a welcome pandemic diversion.

For the whole truth’s sake, I should say that I didn’t read them, literally, only listened to the audiobooks, which counts the same as far as I’m concerned. Length notwithstanding, they’re fast reads, the kind the make you take the long way home or look forward to the chores you can do while listening. You’re not going to stay up all night and finish, but the reading-pace-to-page-count ratio is high in my experience.

Caro is as elegant a storyteller as he is dogged an investigator. In four books that together run well over 4,000 pages — with the 1964 electoral landslide and the political death throes that followed still ahead, “to be continued” style — historical figures come alive on the page. Names now affixed to congressional office buildings, like Southern legislative stalwarts Sam Rayburn and Richard Russell, seem at times almost as if they were Caro’s subjects, so vividly they’re portrayed.

Johnson’s political contortions provide plenty of plot twists. Elected to Congress in 1937 as a supporter of FDR’s court-packing plan and an unabashed New Dealer, he became a loyal servant of tycoon donors. At the same time, he did the legwork (and arm-twisting) on behalf of the literal and figurative powerless to get his rural district wired for electricity.

In the 1948 Senate campaign, he drifted right to compete against his more conservative Democratic primary opponent, former Texas governor Coke Stevenson. That victory, in Caro’s meticulous telling, involved fraud beyond even the electoral chicanery common in the state at the time.

A decade later, the presidency now within reach, Johnson angled left again, shepherding the first civil rights bill in decades through Congress, one of those moments when his compassion and ambition merged. As much as championing freedom, the bill was among Johnson’s efforts to wash off “the taint of magnolia,” the southern stigma he would have to overcome among Democratic constituencies in the north.

That he was outmaneuvered for the 1960 Democratic nomination was a rare political miscalculation. The smart money early on would have been on a Johnson-Kennedy ticket, not the other way around. When his moment arrived, though, Johnson soft-shoed his pursuit of the one job he wanted all his life.

In Caro’s estimation, Johnson downplayed his intentions because he feared humiliation if he were seen to covet the job and then lose. That and because the great “reader of men” misread callow Senator John F. Kennedy, the cad who had accomplished so little in his lackluster congressional career. Kennedy, in fact, proved to have clambering stamina comparable to Johnson’s.

So the course of history escorted Johnson from the heights of power as Senate majority leader into the relative isolation of the vice presidency. Then Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas — in the home state of the new president, no mere point of trivia in that traumatized moment — thrust him into the Oval Office under the worst imaginable circumstances.

In the following days, he led the country with a statesman’s grace that, Caro notes, he would not sustain. How the tumult that followed went down will be the focus of the fifth and final installment, but what Caro has already constructed could — should — stand in lieu of a monument, a blueprint for how we might best remember our leaders.

The volumes don’t provide a pedestal for Johnson — or a bludgeon to dethrone him. They represent instead the sturdiest of life stories, a study of the man, his times, the messy ambiguity of pursuing and wielding power in a democracy, and the reverberating consequences of life and death decisions ceded to the elect.

And Caro hasn’t even gotten to Vietnam yet.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.