Usually, I don’t look very hard for books. The good ones seem to find me.

Most come as gifts or loans from friends or family. Others leap into my hands from shelves at used bookstores or thrift shops.

I’m grateful for that convenience. With some 300,000 new books printed annually in America, as well as a million or more self-published or e-books, I don’t like seeking intelligent life somewhere in the twinkling night sky.

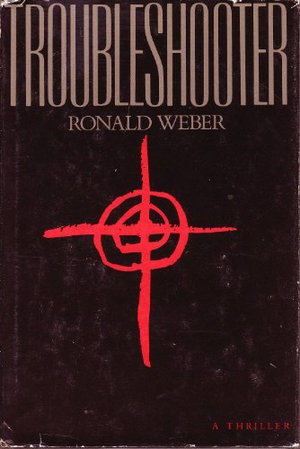

I made an exception with Troubleshooter, a 1988 spy novel written by Ronald Weber.

Professor Weber headed the American Studies department in the 1970s, during my years at Notre Dame. He taught a course called The American Character, which plumbed the works of Twain, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Updike and others for a common theme.

I could explain it, but it would take me three hours a week for four months to do it justice. Try this image: Daniel Boone, disenchanted with the civilized ways in his settlement, crosses a mountain range into a new frontier. There, full of optimism, he builds a new settlement that will become exactly like that constricting place he left.

This is our character. It is what we Americans do.

Fitzgerald said it this way: “We beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” I say it this way: We know our faults but we carry them with us, like spores, to whatever fresh, fertile ground draws us.

Weber’s class prepared me for this world where I must choose between Trumps and Clintons — versions of flawed characters I met in books by Fitzgerald and Steinbeck. Because I understand, I’m not driven blindly toward hatred or despair. We will continue to strive even after we inevitably fall.

Forty-four years removed from Weber’s class in O’Shaughnessy Hall, I wondered if he had ever released these insights into the public air. A Google search informed me that he had written a dozen books, fiction as well as nonfiction.

I read a blurb about Troubleshooter and was curious. I’m not a book snob, but I would put most spy novels on an aisle between the microwave noodles and instant coffee. If you read the labels, you know that the key ingredient is water.

Still, I found a copy online at an Oregon thrift store and paid a dollar, plus postage.

The basics of Weber’s plot are these: Main character Robert Laski is a Princeton professor specializing in the works of Thoreau. He is asked by a family friend, Margaret Tate-Manders, to accompany her to Portugal to search for her husband, who has failed to return her calls.

The novel is set a decade or so after Portugal’s military coup of 1974 brought a communist regime to power. As it turns out, Margaret’s missing husband, Tommy, is working with one of the revolution’s heroes, Jaime Ramalho, who has become an embarrassment to the new government. Instead of championing the people, Ramalho has spent his time in a resort town, learning to sail while he and Tommy profit from the buying and selling of high-end art.

The spies in this book are about as distant as you can get from Ian Fleming’s James Bond. There are no gadgets, no flamboyant villains, no mysterious women. The intelligence agency produced by Weber relies more on middle-aged professors who discuss what needs to be done and who approach the task with some dread.

The strength in this novel isn’t the story; it’s in the telling. The twists are few and, once the stage is set, the action proceeds as plotted. If you’ve read spy novels, you know early that there are only a handful of ways the story can end.

Weber’s gift is infusing the genre with intelligent prose. Pick any page at random and you’re likely to place your finger on elements of excellent writing. And like Hemingway, Weber is alert to our needs. He knows when to describe the sights of Portugal, a place few of us have been, but he also senses when his readers and characters are getting tired and simply desire to move along.

Hemingway knew there was literary beauty in directly translating Spanish idioms into English, and Weber does the same with Portuguese. When native speakers converse in their own tongue, the translations offer subtle insights on how their language descends from clever ancestors.

This, for example, is the brusque exchange at gunpoint between an assassin and an old waiter whose misfortune is that he bumped against the killer’s weapon.

“This is the object you felt.”

“I felt no object.”

“If you had felt one, you would have felt this.”

“I have no memory.”

“If you had a memory, you would remember this.”

As you read, you find phrases that conjure my holy trinity of Fitzgerald, Hemingway and Steinbeck but also a whiff of Graham Greene and other authors whose names should be in your college notebooks. It is not a theft. Picasso does not own blue. Butter and cream belong to us all, not just to Julia Child.

Professor Weber taught hundreds of students at Notre Dame, and many of us might second-guess this spy novel as unworthy of an enlightened scholar.

It is not our decision to make.

Compare him with Laski, the book’s main character, who has spent his career professing about Walden Pond in Princeton classrooms without really knowing Thoreau. He speaks in comfort until he is forced into action by a family friend.

Most of us do that. We tell our stories of family and work from our seats in the shade. We are inadequate stand-ins for those we observe and admire.

Professor Weber isn’t Hemingway or any of the authors whose books he revealed to me. But he sat down one day with a story in his head. It turned into words and chapters. When he finished, he gave us a chance to learn about the beauty of Portugal and the angst of weary men who are there because they follow orders.

This book isn’t For Whom the Bell Tolls. But it’s a complete novel, with words worth reading. For that alone, and the lessons long ago that have shaped my life, I tip my cap.

Ken Bradford is a freelance writer and former reporter and editor at the South Bend Tribune.