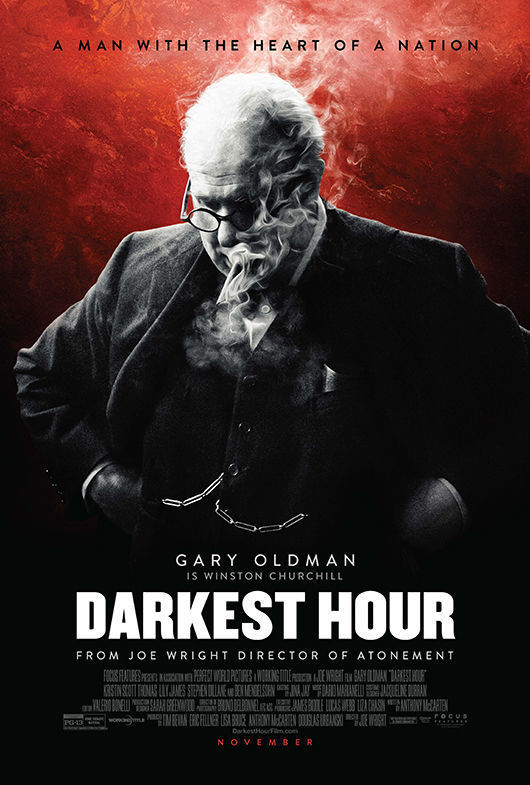

Watching Gary Oldman play Winston Churchill in Darkest Hour you see the marriage of a man and his moment in the making of history.

For Churchill, his first 65 years before becoming the United Kingdom’s prime minister in May 1940 served as a prelude to wartime leadership that continues to fascinate anyone who believes freedom demands vigilance and defense, whatever the cost.

Darkest Hour emphasizes what’s most important about Churchill — his rare ability to use the English language as his principal tool to instruct and inspire the public. His words were always his own and as much a part of his character and personality as the constant presence of his cigar.

In the popular imagination — from films like Darkest Hour or John Lithgow’s engrossing portrayal of Churchill in the Netflix series The Crown — people learn about a public figure elevated to be head of the British government twice: in the early 1940s and, a decade later, in the early 1950s.

What many people today don’t realize is that out of office and from his 20s on, he was a professional writer, who published millions of words in books and articles. (One estimate of his lifetime output is 11 million words.)

This literary training and linguistic facility became the foundation for Churchill’s way of governing, a point Darkest Hour makes clear by focusing on three key speeches he delivered during his first weeks as prime minister.

Three days after King George VI asked Churchill to form a new government, the new PM told the House of Commons “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.” The sentence is personal and precise.

He then moves beyond the individual to what awaits the country as a whole — the “we,” the “our,” the “you.”

We have before us an ordeal of the most grievous kind. We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering. You ask, what is our policy? I can say: It is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our policy. You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: It is victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival. Let that be realized; no survival for the British Empire, no survival for all that the British Empire has stood for, no survival for the urge and impulse of the ages, that mankind will move forward towards its goal.

In the film, you see the power of those words in the reactions of the members of Parliament. The repetition of “victory” and “survival” rang in their ears back on May 13, 1940, and continue to do so for us, almost eight decades later.

Promoting Darkest Hour, director Joe Wright told The Washington Post that “I find the history interesting — and, dare I say, educational — but what I really wanted to tell was a story about a character who doesn’t fit in.”

Churchill was often the odd man out, the rascally bulldog in the China shop of British affairs. Several members of the government before Churchill was selected as prime minister — he didn’t win high office in an election of the people — harbored serious reservations about the long-time member of Commons and prolific wordsmith.

As the film shows, he could be difficult to work with and intermittently irascible. But he knew his mind and what mattered at the time when he finally had the opportunity to take charge.

Most importantly, he knew what to say. After the evacuation from Dunkirk — an event also recently dramatized on film — Churchill returned to the Commons not just to talk about what had happened but also about the future.

Darkest Hour helps drives home Churchillian determination by concentrating on the passage below with its relentless invocation of the definite “shall”:

Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, and even if, which I do not for a moment believe, this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the Old.

These are the final sentences of his speech. Churchill desperately wanted America to become involved in the war and kept dropping hints in speeches and meetings. This, however, didn’t occur for another 18 months. Many dark days.

As successful as Darkest Hour might be in rendering Churchill — words and all — a hokey scene of an unaccompanied prime minister taking a London subway ride to talk to the common people about the war gives new meaning to dramatic license. He did get out among the people, particularly to survey damage from German bombing, but listening to the vox populi on a Tube journey strains credulity.

A couple weeks ago, The Observer, a British newspaper, published this headline to draw attention to its review of “Darkest Hour”:

Winston Churchill makes a fine movie star. If only we had a leader to match him in real life today

That’s true. But the likes of a Churchill come along so rarely that movies and books about him continue to appear with such regularity to remind us all what great leadership can be and what it can accomplish. Those are timeless lessons.

Robert Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Professor of American Studies and Journalism at the University of Notre Dame. He recently served as a Visiting Research Fellow at the Rothermere American Institute at the University of Oxford, where he worked on his forthcoming book, Mr. Churchill in the White House.