1

I might not have come to understand what I came to understand if I hadn’t been skimming my way through Lewis Hyde’s The Gift at the same time I was making a video of our trip through my friend’s home state of Washington nearly two years ago. The images have a loveliness missing from my life since my wife died in 2015. This was my first time looking at the photos since I had taken them, and I couldn’t stop playing the video. I played it over and over. I had no idea it would be so beautiful. I had no idea it would be such a gift.

The woman in the video is a friend I had come to care much about since meeting her in Sun City, Arizona, where we both have second homes. Shortly after our initial meeting, she broke both tibias when a mat flew out from beneath her feet as she was taking a yoga class. I visited her in the tiny institutional rooms she was confined to for the next three months. I read her The Little Prince, Loren Eiseley’s “The Judgment of the Birds,” David Foster Wallace’s This Is Water, and for hours each night we talked away the loneliness of those tiny, confining rooms, and we became close.

I was so taken by the video — I didn’t feel like I was its maker as much as I felt like I was the recipient of a gift — that I wanted to pass on this gift to her. So I sent it to her, and she wrote back that it was nice but the volume was too loud. That was all she had to say about my gift.

I was crushed. Only then did I begin to connect my video to Hyde’s book. Only then did I begin to understand the deep, unspoken and little-understood role of gift in my life and the lives of every one of us on this planet.

In a conversation with my friend about the video, I did not tell her how crushed I was by her failure to see it as a gift of love, but I did tell her I thought of the video as a gift. That’s when she began to list things that were gifts in her life. At the end of her list, I said that most of the things she mentioned were not true gifts as I was coming to understand the term. They were favors friends had done for her, blessings that had come her way through good fortune, kindnesses and courtesies paid — but they weren’t really gifts in the way I was coming to understand this misunderstood and un-thought-about term.

What did I mean? she asked, genuinely interested. I said I would puzzle out what I meant in an essay. This is that essay.

2

The Gift, acclaimed as a classic, is not for the faint of heart. Much of it is anthropological. Hyde is looking at how profound, deeply entrenched and worldwide is the custom of giving gifts. But it turns out that only a few scholars have given serious thought to the nature of giving gifts. Hyde is one of those rare people.

Though much of what Hyde writes is of little direct use to my thinking about gifts, a few passages exploded my formerly dull nonthinking, revealing for me a whole new understanding of what a gift really is and why we give them and how they are accepted or not accepted and what they really do for the people giving and receiving them.

Hyde begins his book, however, with an aspect of gift I already knew very well, the gift all artists know: the gift of inspiration. This word, of course, means “breathed into.” Every real artist knows it. It is not the result of mere talent or hard work. It is not something earned. Inspiration is a gift.

“As the artist works,” Hyde writes, “some portion of his creation is bestowed upon him. An idea pops into his head, a tune begins to play, a phrase comes to mind, a color falls in place on the canvas. Usually, in fact, the artist does not find himself engaged or exhilarated by the work, nor does it seem authentic, until this gratuitous element has appeared, so that along with any true creation comes the uncanny sense that ‘I,’ the artist, did not make the work. ‘Not I, not I, but the wind that blows through me,’ says D.H. Lawrence. Not all artists emphasize the ‘gift’ phase of their creations to the degree that Lawrence does, but all artists feel it.”

I read Hyde’s words with recognition and gratitude. For 50 years I have known that something outside myself, something even divine, was breathing itself into my writing when it was truly alive. Almost every essay or poem I have ever written begins with an inspiration. It comes, I believe, as a gift from God.

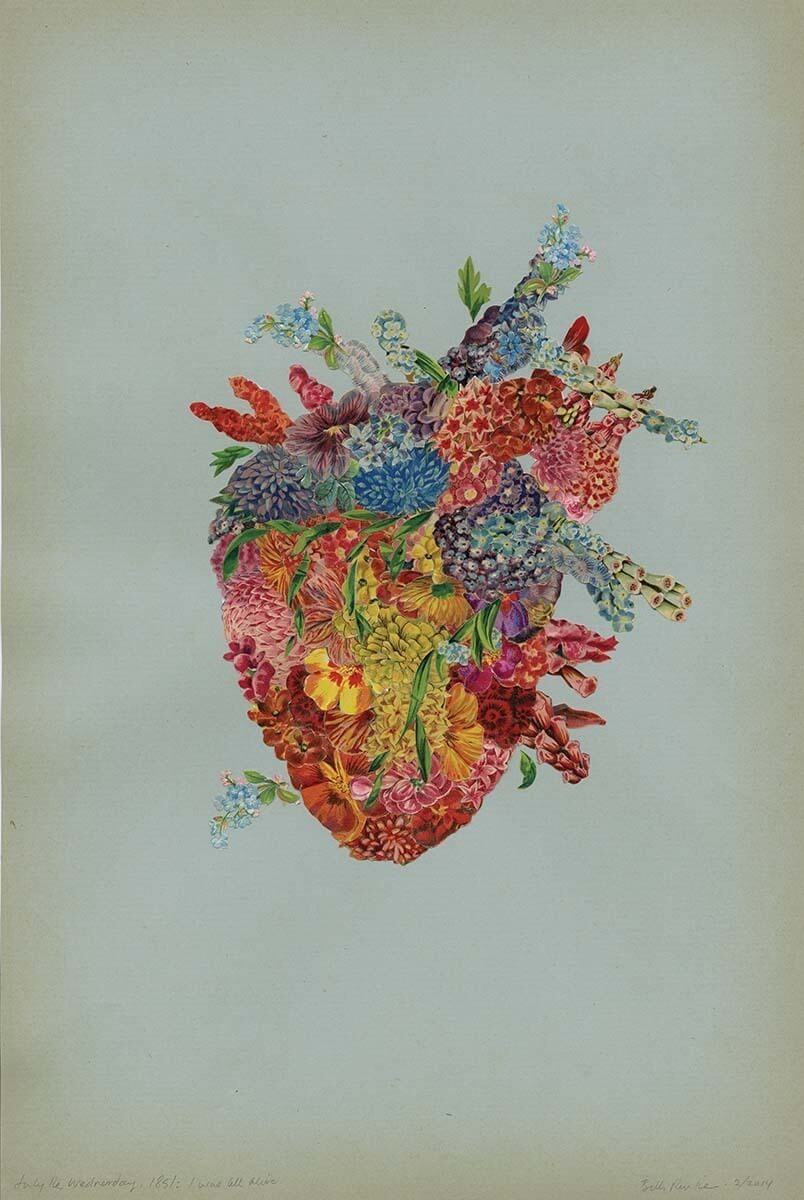

I was also familiar with the flip side of the matter: the gift that art is to the viewer, listener or reader. Hyde writes, “That art that matters to us — which moves the heart, or revives the soul, or delights the senses, or offers courage for living . . . that work is received by us as a gift is received. . . . The spirit of an artist’s gifts can wake our own. . . . We may not have the power to profess our gifts as the artist does, and yet we come to recognize, and in a sense to receive, the endowments of our being through the agency of his creation. We feel fortunate, even redeemed. The daily commerce of our lives . . . proceeds at its own constant level, but a gift revives the soul.”

How many times have I been lifted from mere existence, mere comprehension — the necessary dailiness of life — into the rarified atmosphere of knowing and being and understanding that I had not known before reading a poem, an essay, a story, a novel?

Though it happened for me a full 50 years ago, I can still see that moment at the end of Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie when the narrator and chief character, Tom, steps out of the shadows of a darkened stage and into the spotlight smoking a cigarette and speaks the haunting last words of the play. The first words of that speech are still with me: “I didn’t go to the moon, I went much further — for time is the longest distance between two places.”

That night, only 33 years old and sitting beside my wife in that small, low-cost suburban playhouse, I was gifted with a knowledge of memory and time and regret that has stayed with me the rest of my life. Much of my writing life since then has come from that knowledge.

A little later in his book, Hyde looks at the greatest gift of all, the uber-gift, the gift of life. Here I am indebted to Hyde for resurrecting Meister Eckhart’s profound words on the nature of this gift, written seven centuries ago.

“For Eckhart,” Hyde writes, “all things owe their being to God. God’s initial gift to man is life itself, and those who feel gratitude for this gift reciprocate by abandoning attachment to worldly things, that is, by directing their lives back toward God. . . . The Lord pours himself into the world, not on a whim or even by choice, but by nature: ‘I will praise him,’ says this mystic, ‘for being of such a nature and of such an essence that he must give.’”

I have italicized the words above because they came over me in a sudden flash of understanding. Not just God’s gifts but true gifts from one human being to another, I suddenly understood, are never mere deeds or things; rather, an essence or state of being is the real gift. Whether it is the gift that comes to an artist in the making of art or the gift that comes to a reader or viewer in receiving the art, or a gift of any other kind from one human being to another, a true and real gift is never a thing or a deed. An essence of being is the real gift.

In that moment, I understood why I had been so crushed by my friend not receiving my video for what it was, a gift of love. In the next moment, I understood something even more primary: that I hadn’t given only my friend a gift; I had without knowing it given myself a gift. That was why I could not stop playing the video over and over. It was then I understood the true nature of gift for all of us. Which is when I finally saw the perversion of gift that has taken place in the modern world: the purchasing of things in the marketplace to hand over to someone we love because of a date on the calendar.

That night, only 33 years old and sitting beside my wife in that small, low-cost suburban playhouse, I was gifted with a knowledge of memory and time and regret that has stayed with me the rest of my life.

3

When you and I speak of gifts in our everyday lives, we do not use the term “gift” so profoundly. Instead, we use “gift” interchangeably with “present.” Sometimes we also use it interchangeably with “blessing.” Or we might use “gift” in place of saying someone did us “a favor” or paid us “a kindness” or did us “a courtesy.” In common parlance these words are quite interchangeable. But now, for the sake of understanding our world as a more spiritual place than we normally suppose or understanding the depth of our emotional lives, I want to separate the word “gift” from these other words.

I will begin with small things. At the moment, I am thinking of the personal birthday cards I have been making for friends and family for some 30 years. They came about because by the time I was 50 I realized Hallmark and American Greetings weren’t saying what I wanted to say, nor were the images on their cards, pretty though they are, the right ones for the recipient.

As a photographer, I had lots of images — often those images were of the person I was sending the card. Using those photos and a high-gloss cardstock, I no longer had to purchase manufactured sentiments. I could give, to someone I cared about, not something bought in a store but who I was and who the person was. Though I couldn’t have articulated it at the time, I was beginning to understand “gift” as very different from “present.”

Similarly, for my sons’ confirmations, I found some sheets of thin, pliable leather I could fold into a book cover. Then I found some cream-colored vellum to make the pages. I folded them over, stitched them inside the leather cover, and wrote my thoughts about this sacred occasion. I had high hopes for their spiritual lives.

Recently, in my company, one of my sons was going through things he had saved over the years, when he came upon the confirmation book I had made for him 40 years earlier. He held it in his hands with awe. It was still with him because it was a real gift, not a present.

Sacred. That is what most distinguishes gift from present. Real gifts are sacred. Presents are secular. Real gifts remain in memory. Presents slip out of mind. When we give our selves, we give what no one else can give. We endow a moment with timelessness, even if time will eventually erase that moment. My words are a contradiction, of course, but they are a contradiction at the heart of human being. We are at once sacred and eternal, and at the same time perishable and doomed to the passing of time. Gifts celebrate the sacred. Presents only manage the occasion.

For my 80th birthday three years ago, my sons gave me an extraordinary gift. For 52 weeks I would receive one question about my life each week from a company named Storyworth. During the next year, I spent anywhere from four to 80 hours answering each question. Sometimes it took a month to answer a question, sometimes only part of a day. At the end, I had 30 copies printed and bound. It took a thousand hours and $3,100 to make A Life in 52 Questions. A year and a half after my 80th birthday, that book was my Christmas gift to my sons and stepchildren and step-grandchildren north of 18. Each year for the next seven years it will continue to be my high school graduation gift to my remaining grandchildren. Yes, I am fully aware that for the moment they would rather celebrate their achievement with a present of money. But 30, 40, 50 years from now, I hope they will treasure the gift I have given them.

In my book and in my cards and in my confirmation booklets, I have been trying to quicken my words by yoking love with beauty and what I hope is truth. I want my words and the images I choose to leap from my heart to the receiver’s heart. I want my cards and books to defeat time and space, at least for a while. I want my words and photos to be alive in the receiver’s hands. If I succeed, my cards and books will be true gifts.

When Hopkins splays himself against a bare wall and cries for his mommy, I sobbed, fully realizing for the first time what my wife had gone through in her descent.

4

It occurs to me that this is what happens when writers make literature and when photographers capture scenes and faces and when artists turn tubes of color into images that arrest viewers’ eyes. When writers succeed in creating literature, they make us want to read their words again and again, to listen to their sounds and cadences and meanings over and over until they live in the reader’s heart as they did in the writer’s. When that happens, Hemingway and Faulkner and Frost and Fitzgerald and Dickinson and Whitman defeat space and time. When that happens, what the writer or other artist has breathed in is exhaled into the reader or viewer. When that happens, a gift crosses the boundaries of souls. For that is what all gifts do — bring souls together.

Sometimes entertainers do this, too. Jackie Gleason wasn’t even close to being a great comic mind, nor does anyone think he was more than a journeyman actor. His skills weren’t his gift. His gift to audiences was the way he gave his entire flawed and hurting self to what he did on stage. I was 12 when Gleason took over the Cavalcade of Stars and made it The Jackie Gleason Show. My family and I — and, really, much of the nation — watched Gleason be the Poor Soul, Joe the Bartender, Fenwick Babbitt, but most of all the blowhard bus driver Ralph Kramden. Only 39 episodes of the Ralph Kramden spinoff, The Honeymooners, were made, but millions of viewers are still watching them almost 70 years later. We aren’t watching because they’re so brilliant or funny; we’re still watching because Gleason was giving us the gift of himself, and he did it without reserve.

Anthony Hopkins is another actor whose work transcends performance. No matter whether he is a butler in The Remains of the Day or C.S. Lewis in Shadowlands or Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs or the title character in King Lear, Hopkins is giving us, without reserve, the gift of his soul.

But I have found no finer moment of giving than the last scene of The Father, in which he plays a father descending into dementia. Though my wife and I lived through her 11 years of similar descent, I was not prepared for the power of that last scene. When Hopkins splays himself against a bare wall and cries for his mommy, I sobbed, fully realizing for the first time what my wife had gone through in her descent. I had been with her day and night, but it was Hopkins who made me see in a way that even reality had not made me see what she had gone through. In 70 years of watching films, I have received no deeper gift.

Occasionally professional speakers give themselves so completely to their audiences that they themselves become gifts more than their words and thoughts. The first time I experienced such a gift was while watching motivational speaker Leo Buscaglia talk to an audience of several thousand for Chicago’s PBS station, WTTW, in 1983. I have watched him dozens of times since then, and always for the same reason, because I wanted Leo Buscaglia to be with me.

During the 1980s and ’90s, when Buscaglia was giving talks all over the country, my English department colleagues thought he was a lightweight. I suppose they were right. He said nothing new, didn’t explain difficult matters, didn’t probe the human condition deeply. But when he talked about Mama and Papa and the closeness of family and the preciousness of life and the need to give your heart to others and to forgive those who hurt you, he did it with a passion and urgency all his own. He was family and intimacy and forgiveness and joy and love itself. Sometimes, when darkness clouds my life, I watch one of his talks on YouTube. They lift me from aloneness. He died at 74 of a heart attack in 1998. Twenty-five years later I cannot speak his name without remembering the gift he has been to my life.

I could write a short book about the gifts teachers have given me — but right now I will mention only two moments. Though it is now nearly 60 years ago, I still remember that Friday morning in March 1965 when a serious literary scholar named Jim Stronks stood before our class at the end of the period. Tall and thin, with searching blue eyes, he looked at us a long time before he leaned forward, placed the fingertips of both hands on his desk, leaned his weight on those fingertips, and after continuing to look at us still longer, finally said, “I envy you your first reading of this novel.” His words were almost a whisper.

That novel was Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms. Jim’s gift wasn’t the novel; it wasn’t even his recommendation; it was his person tangled together with that novel in that moment. Because this gift was so slight and momentary, because it seemed in that moment to have less weight than a feather, I didn’t at first get it — I was only 24 and had no idea yet what a real gift was — but eventually that gift emerged from a life of unknowing and unseeing and came to haunt my reading, writing, teaching and living.

The other gift of a teacher came eight years later, on the final day of the toughest course I ever took. Jim Barry had us reading seven Dickens novels, only one of which had fewer than 500 pages, and three Eliot novels, and writing eight short papers and one long paper. I spent nearly 70 hours a week reading and writing for that course, many of those hours in a state of joy because Dickens always got to the heart of life and because Barry was the best and most quietly loving teacher of my life.

On the last day of class, he put into our hands a mimeographed sheet of paper with four quotations on it. The first two passages were literary critics reflecting on the nature of Dickens’ work; the third was an essayist considering the Redemption; the last was Psalm 8:2-7. “When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers,” the psalmist wrote, “what is man that you are mindful of him? . . . Yet you have given him dominion over the works of your hands.”

Barry himself was silent; he put only those passages in that order on the page in blue mimeograph ink. The whole course had been the finest gift I ever received in a classroom, and this was the culminating gift — only I didn’t know it then.

It would be 40 years before I opened the folder of things I saved and notes I took from that course and came upon this sheet of paper that, when I brought it to my nose, still had the smell of mimeograph alcohol on it. From my first reading I knew these passages contained more than information or knowledge. After several readings I realized that they constituted a prayer for the dozen or so of us taking that course to deepen our humanity so that we would finally aim our lives at God.

Barry did not intrude on the prayer. With utter humility, he simply put it into our hands and trusted we would get it. It took 40 years for me to get it, but I finally did, and for the last 10 years, in those moments when I have remembered those passages, I have realized that I have lived my life, whether I knew it or not, in the shadow of this prayer. It was the humblest, subtlest, most profound gift I have ever received.

Though I could cite conversations with friends and strangers that were gifts to my life, I will refrain. Such conversations have saved my life over and over, not from death itself, but from something almost as bad: death in life. How did I make it through those early years, I find myself wondering now, and how do I make it through the many days even now when there are no such conversations, when there is no gift of the other speaking his or her heart to mine and my speaking my heart back to the other?

Stoicism, I suppose. And reading and writing. All three — conversation, reading and writing — have been incomparable gifts in my life. But it would take too long to tell you of these gifts which are, essentially, a deep sharing, a give-and-take, between two souls. Besides, I can give the essence of all three in Bertrand Russell’s description of his first meeting with Joseph Conrad. “We talked with continually increasing intimacy,” Russell wrote. “We seemed to sink through layer after layer of what was superficial, till we gradually both reached the central fire. It was an experience unlike any other I have ever known. We looked into each other’s eyes half appalled and half intoxicated to find ourselves in such a region.”

So now, after a long and winding road of thinking about the nature of gift — not gifts, but gift — I return to the video I gave my dear friend, that she thought was “nice but too loud.” I will simply give her my words just as I have written them here and hope she understands why I was so crushed by her not receiving my gift. But when I give her these words I will also thank her for not getting my gift, for by her not getting it she set me to thinking long and hard about the nature of gift, and this, too, has been a blessing.

Mel Livatino lives in Evanston, Illinois. A regular contributor to this magazine, he has published in The Sewanee Review, Portland magazine and other journals. Since 2004, 12 of these pieces have been named notable essays of the year by Robert Atwan’s Best American Essays, and he has recorded nearly 50 of them for Recorded Recreational Reading for the Blind in Sun City, Arizona.