My friend was partially joking when he asked me whether my interest in Timothy McVeigh meant I was masochistic. The Oklahoma City bomber had been interviewed in prison by journalists Dan Herbeck and Lou Michel, who together wrote a fine book about him, American Terrorist, and then donated 45 hours of recordings to the library at St. Bonaventure University, Herbeck’s alma mater — and I was listening to the tapes. I was interested in McVeigh for a reason that might seem unconnected to the suffering and death he wreaked, depending on how broadly you are willing to define mass murder.

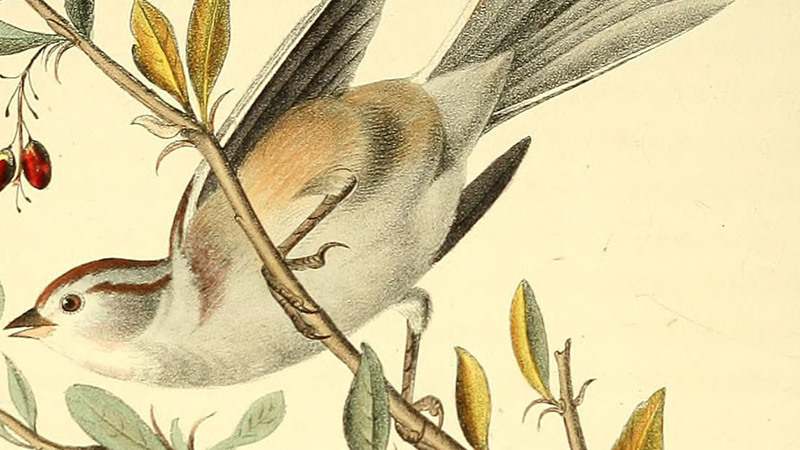

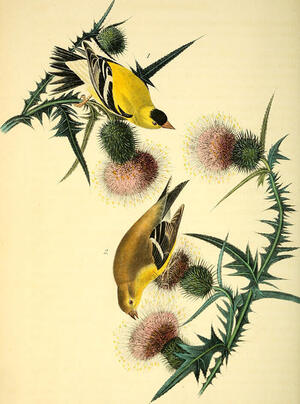

I was listening because at summer nightfall I can no longer witness the shadowy grace of brown bats or hear faintly the click of wing meeting wing when in its darkness within the deepening dark a flying mammal veers away just short of my head; listening because on spring dawns when I go outside to enjoy a new day I hear many fewer birds than I could a couple of decades ago, half the orchestra absent from the stage, and because I seldom hear any longer the dusky peent of a nighthawk looping somewhere over moonlit meadows, or the gentle and polite burping calls of leopard frogs mating in my pond; listening because when I press an ear to one of my hives and rap with my knuckles in January, the reply as likely as not will be hollow silence rather than the whirring buzzing of clustered bees, and then more silence as if the silence is echoing; listening because in the increasingly quiet natural world, in its echoing and loudening silences, I feel like a lonely and too-hopeful party guest who lingers long after the departure of the DJ. Listening because I wondered whether in the disembodied, call-in-show quality of McVeigh’s opinions — such as that the grieving families of his victims should “move on” — I could learn something about why so many people are largely indifferent to the silencing of life all around us.

I could hold forth at great length about climate change and other types of human-caused environmental degradation and the extinctions and windstorms and flooding and droughts and fires and ocean acidification and human migrations and economic collapses and wars and declines of civilization likely to ensue. The mass suffering. The mass death. But why repeat what on some level most people already know? Lack of information is not the problem.

We’re tired of hearing about it.

And tired of each other?

It was January, and the more I listened to McVeigh, the colder the outside weather seemed, though winters in my region are becoming warmer and shorter. At home, I burned more wood than necessary, my chimney sending more carbon into the atmosphere.

One afternoon after I had listened to several more hours of the recordings, I visited with a different friend than the one who wonders if I am masochistic. Those who care about this friend are trying to lengthen his life, but this visit was selfish of me; McVeigh was depressing me, and I hoped to be cheered despite my friend’s poor health.

My friend has been unable to give up sugar even though he is a Type 2 diabetic and receives thrice-weekly kidney dialysis. He denies that his congestive heart failure has anything to do with his diabetes, and though his family doctor wants to check his eyesight for evidence of diabetic damage, he has declined to be tested: He can see just fine to watch television and drive and ogle women, so why worry? After he downs, for example, a couple of candy bars or glasses of Irish cream liqueur, he injects himself with extra insulin, which is one reason why his endocrinologist accused him of wasting both her and his time and told him to find a new doctor. He suspects that the actual reason “she fired me,” as he puts it, is she caught him peeking down her blouse. The last time I urged him to change his eating and drinking habits, he waved me off like an outfielder calling a fly ball as his to field, and said, “Everything will be OK.”

During our visit, we talked about our families and mutual neighbors, the football game on TV, the weather, and the scores of whitetail deer digging for clover out in his snow-covered hayfield. We kidded and laughed some, though I found it hard to keep from staring at the bulge where his shirtsleeve covered the grafted dialysis catheter, and I didn’t tell him about my day with the recordings or say anything about his diet. Since I desired to feel better, I also didn’t bring up the health of our local forests and wildlife; anyhow, since I had heard it from him twice before, I knew that most likely he would respond, “Nature is resilient.” Once, with a self-mocking grin, he added, “Like me.”

I used to be cheered by hiking or snowshoeing a mature woods that I own a quarter-mile from my house. I intended to donate the property to a land conservancy and assumed that many of the trees would outlive me and every person I knew. I’ve refused to let loggers even talk to me about “harvesting” the trees. The woods used to lift my spirits no matter what was happening in my life and the wider world, but now I fight grief as I hike; the many white ash trees are beginning to die because of the invasive emerald ash borer. It is one thing to know I will die and altogether another to know the woods will soon follow me.

Many of the other trees in the woods are sugar maples, which are stressed and declining for various reasons. Most of the beeches are already dead because of an invasive bark disease and various fungi, and the chestnuts and elms are long gone. A hundred miles away in the Finger Lakes region of New York, a new fungus is killing oaks; and on the East Coast, attempts are being made to control the Asian longhorned beetle, an invasive that prefers maples but will attack and kill any deciduous tree. The southern pine beetle and the hemlock woolly adelgid are advancing northward as the climate warms, killing conifers.

But maybe you already knew most of this.

And don’t you wish you would never hear about any of it ever again?

Lately I have taken to shoving a refrigerated can of beer into my coat pocket before I snowshoe in my woods, and although my consumption of the cold liquid lowers my body temperature out on the snow, I don’t quite notice, thanks to the alcohol. Maybe if I lugged along a six-pack, I would feel better by speaking drunken nonsense. Listen trees, we’re just in a natural cycle, don’t worry, don’t blame, move on.

McVeigh ‘looked into the camera and remained silently faithful to his original script, mute in his role as indurate freedom fighter and avenger.’

Timothy McVeigh grew up in Pendleton, New York, when it was still a blue-collar bedroom community, as it was when I grew up there. Back before climate change became — if you will excuse the pun — a hot topic. He was executed in 2001. From his grave he seems to be teaching violent anti-government marauders how to bring down the American state, but I was listening to the Michel and Herbeck tapes in hopes of learning something else.

The Pendleton of McVeigh’s boyhood had its share of social ills. He was bullied by other children and emotionally wounded by the divorce of his parents. In other words, his childhood wasn’t terribly unusual in Pendleton. When he was a young man, the United States Army trained him to kill and sent him to fight in the Gulf War, but again the course of his life wasn’t especially unusual; I knew quite a few combat veterans. Only one person who grew up in Pendleton became a terrorist.

In the interviews, McVeigh tended to cite movies and TV shows when explaining his belief in natural law, which he confused with Darwinism, and variously expressed his passions for small government, guns, survivalism, conspiracy paranoia and the myth of rural self-reliance. I’ve never heard anyone defend McVeigh, but in my local gin mills and on talk radio I so often hear variations of his angry and yet robotic political and social beliefs that they seem like background noise, the ringing of tinnitus occasionally interrupted by the breaking of glass at the other end of the bar or the crackling of the radio during thunderstorms. But I wanted to hear something else. I listened for quite a few hours before I learned what I should have already understood — or had fooled myself into thinking I didn’t.

Some of McVeigh’s favorite films and shows were Heartbreak Ridge, Mars Attacks!, Independence Day, Little House on the Prairie, Logan’s Run, The Omega Man, WarGames, The Call of the Wild, Damnation Alley and especially Star Trek. As he spoke, he seemed to be splicing scenes from his favorites into a film with Timothy McVeigh as the hero who resists gun control and taxes and avenges the FBI’s disastrous assault on the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas, by bombing a federal building filled with Oklahomans, including the infants in the daycare center. He expressed no compunction about his crimes against the characters in this movie. He was irritated that those he maimed and the families of the 168 people he murdered continued to grieve and to wonder why he believed that so many innocents — in one interview he referred to them as “collateral damage” — needed to die. He obviously wished they would be quiet.

If he had escaped arrest in the hours after the 1995 bombing, he would have camped out in a desert, not to hide, he said, but “for the adventure.” I suppose the arid and often silent environment would have been a good place for him to finish imagining his heroic role in his movie. Freud might have been right when he asserted that people create the god they long to be. In an interview with Lou Michel, McVeigh speculated that an amorphous power was behind the universe, indifferent to life on Earth. In a later interview, he characterized himself as an agnostic, which reminds me that agnosticism has a degree of similarity to deism, both rejecting any certainty of transcending value, the meaning of life left for mortals to find or create — or destroy.

Yet according to news reports of the time, the convicted killer asked to meet with a Catholic priest to make his confession and seek absolution before his execution. I don’t mean to equate McVeigh’s crimes to the magnitude of Holocaust organizer Adolph Eichmann’s, but McVeigh’s meeting with a priest calls to mind Eichmann’s behavior in the final minutes of his life. Hitler’s genocidal bureaucrat claimed to disbelieve in the possibility of life after death, but eventually, standing on the gallows in Israel, he said, “After a short while, gentlemen, we shall meet again” — public theater in which Hannah Arendt famously heard a “lesson of the fearsome, word-and-thought-defying banality of evil.” McVeigh’s confession to the priest was private, but I suspect he was still pondering an alternative ending to his movie, although when later offered a chance to say last words as families of the murdered watched and listened to his execution unfolding on closed-circuit TV, he looked into the camera and remained silently faithful to his original script, mute in his role as indurate freedom fighter and avenger.

Arendt was correct to point out the banality of evil, even of particularly horrendous evil — but all of us flounder in the crosscurrents of our banalities. Was there a precondition for the confluence of McVeigh’s banality and evil? During one interview, the mass murderer was asked whether he had ever loved anyone. He wasn’t sure. He said he’d think about it and get back to the reporters. Did he love his parents? Nope. His sisters? Perhaps he loved one of them, Jennifer, who believed in his innocence until he admitted his role in the bombing to Michel and Herbeck, but his feelings for her were ambivalent. In a different interview, he confessed, “I’m indifferent to life.”

Of course, his inadvertent explanation for the bankruptcy of his soul prompts another “why?” — but his selective indifference to so many lives is as far as I am able to peer into his desert.

And ours?

Because McVeigh’s voice was making me queasy, when I was halfway through the tapes I decided against continuing. I would make a terrible journalist. It was a clear, windless morning, and I felt the need to visit my threatened woods.

Snowshoeing had been difficult for a couple of days, the weather intermittently drizzly, clumps of melting snow clinging to the crampons, weighing and slowing my progress, stiffening my aging hips, but during the night before the clear morning, single-digit temperatures had transformed the surface of the snowpack into thick crust. In the rebounding morning sunshine, and even though the crystallized surface of the frozen snow resembled white sand in the glare, I felt like I was skating rather than snowshoeing. I tipped back my head, eyes squinting and watering, following boles into their naked crowns and the hovering blue. When eventually I tired, I pushed snow from a thick decaying log and sat down. It was nearly noon by then, and there was yet no wind. I was far enough from the nearest road and house that I could hear no passing vehicles or children playing outside, or other human sounds, nor, eerily, did I hear any chickadees or jays or other birds — as if I was in the seventh day of creation and God, already weary of earthly life, had just pronounced that eternal silence is good.

Mark Phillips lives in southwestern New York. He is the author of a memoir, My Father’s Cabin, and a collection of essays, Love and Hate in the Heartland.